Explore France’s Loire Valley in the Footsteps of Leonardo da Vinci

Five centuries after his death, visitors can pay homage to the artist at these sites in central France where he spent his final years

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a9/3e/a93e3118-b03e-4c7d-a59f-7f8e1a4dae64/chambord_castle_northwest_facade.jpg)

Most think of Leonardo da Vinci as being geographically tied to Italy, and for good reason. The visionary artist and scientist spent the majority of his life there. He was born in Vinci, Italy, in 1452. When he was about 15 years old, Leonardo began an apprenticeship with painter, sculptor and goldsmith Andrea del Verrochio in Florence, and joined the city's painters' guild. He spent most of his career in Florence and Milan—studying, seeking to attain perfection through his painting (though it's known that he never felt he had achieved this with the "Mona Lisa"), and inventing contraptions like his flying machine.

However, in 1515, the king of France, Francis I, came to visit Lyons and was greeted by a walking mechanical lion Leonardo built. The king was so impressed that in 1516, he invited Leonardo to come live on the property of his castle in the Loire Valley, where the polymath spent the last three years leading up to his death on May 2, 1519.

During his final years in France, Leonardo's interests focused on engineering and architecture, working at the request of the king on projects ranging from a hunting lodge to a completely contained new capital city. Although many of Leonardo's grandest designs were never fully executed, visitors to the Loire Valley's vineyard-covered landscapes can still see imprints of the artist's genius 500 years later.

Clos Lucé

When Leonardo moved to France upon invitation from the king, he took up residence at the Château du Clos Lucé, a mansion on the grounds of the Château d'Amboise, where King Francis I lived. Leonardo lived the remaining three years of his life in this home, walking through an underground tunnel to see the king—who called Leonardo "father"—in the main residence on the property. The artist brought three paintings with him from Italy to his new French home: the "Mona Lisa," "The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne" and "St. John the Baptist," all of which are now on display at the Louvre. He died in his bedroom in 1519 at age 67 from complications of recurrent strokes.

Today, the mansion has been restored to the way it appeared during Leonardo’s stay there, including his bedroom, his basement studio, the original frescoes on the walls and the high stone hearth in the kitchen. Leonardo particularly loved the colorful stained glass throughout the house. The basement houses about 40 3D models created from his blueprints, and the garden at the property has full-scale representations of some of his inventions, like his assault chariot, aerial screw and revolving bridge.

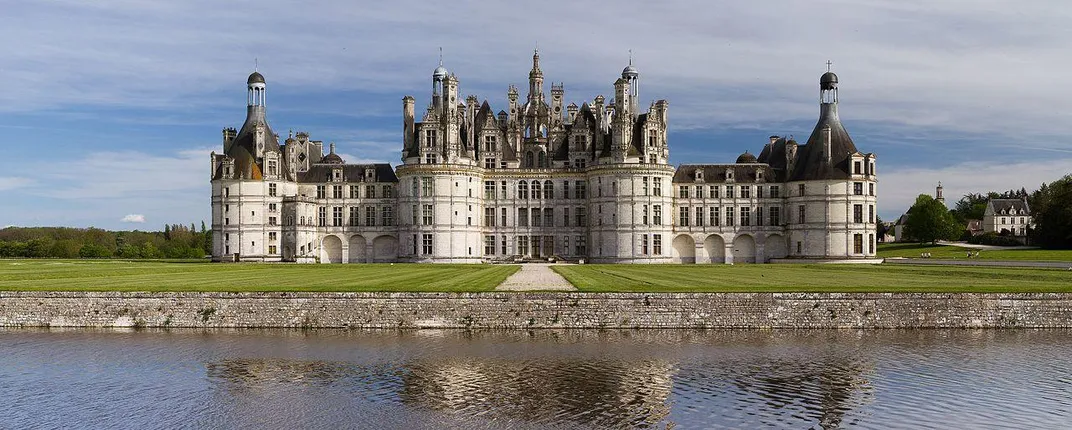

Château de Chambord

Leonardo would never see the final completion of the Château de Chambord; construction was just beginning the year he died. It’s theorized by historians and Leonardo scholars, though, that he designed at least part of the castle. Tanaka Hidemichi, a French and Italian art historian at Tohoku University in Japan, notes that though original plans by Leonardo have never been found and French updates to the castle have obscured some of the architectural history, the footprint of the building is undeniably a Leonardo design. Hidemichi and other scholars point to the building's double helix staircase flanked by identical apartments as examples of the mathematical elegance that hallmarks nearly all of Leonardo’s work.

Visitors today can explore the castle and formal French gardens by foot, or tour the grounds by boat, bike or horse-drawn carriage. Horse and bird shows are also held regularly on site.

Romorantin

Romorantin was a massive undertaking for Leonardo and King Francis I. The king hired Leonardo to design the entire town, creating an ideal utopian city that he expected to become the capital of France. The project—consisting of a canal with water diverted from a Loire tributary, a royal palace, gardens, water mills, irrigated farmland, sewers and suburbs—was never realized. The king put his efforts and energy elsewhere (into the castle at Chambord) as Leonardo’s health began to fail.

Although visitors won’t see the fruition of the pair’s grand plans, Romorantin is still a picturesque town with shops, wilderness activities, restaurants and museums.

Château d'Amboise

The Château d'Amboise is the main estate on the grounds where Leonardo lived out the remainder of his years; the artist’s home was less than 1,000 feet away. From the 1400s to the 1800s, the castle was a royal residence; now it’s a tourism draw with the castle, the gardens, the towers and the underground areas open to visitors.

Leonardo’s tomb is on the grounds, as well. In the early 19th century, much of the palace was demolished, including a chapel and graveyard where Leonardo laid at rest per his wishes. About 100 years later, some bones were discovered on the property that are allegedly Leonardo’s. They were ultimately moved into a tomb in the Chapel of Saint-Hubert, in the castle gardens, marked by a concrete slab with his name, a disc embossed with his portrait and a plaque describing why his bones are there, rather than at the destroyed site.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)