Fairhope, Alabama’s Southern Comfort

Memorist Rick Bragg finds forgiving soil along the brown sand stretch of Mobile Bay

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Fairhope-Alabama-French-Quarter-631.jpg)

I grew up in the Alabama foothills, landlocked by red dirt. My ancestors cussed their lives away in that soil, following a one-crop mule. My mother dragged a cotton sack across it, and my kin slaved in mills made of bricks dug and fired from the same clay. My people fought across it with roofing knives and tire irons, and cut roads through it, chain gang shackles rattling around their feet. My grandfather made liquor 30 years in its caves and hollows to feed his babies, and lawmen swore he could fly, since he never left a clear trail in that dirt. It has always reminded me of struggle, somehow, and I will sleep in it, with the rest of my kin. But between now and then, I would like to walk in some sand.

I went to the Alabama coast, to the eastern shore of Mobile Bay, to find a more forgiving soil, a shiftless kind that tides and waves just push around.

I found it in a town called Fairhope.

I never thought much about it, the name, till I saw the brown sand swirling around my feet under the amber-colored water ten years ago. A swarm of black minnows raced away, and when I was younger I might have scooped one up. This is an easy place, I remember thinking, a place where you can rearrange the earth with a single toe and the water will make it smooth again.

I did not want sugar white sand, because the developers and tourists have covered up a good part of the Alabama coast, pounded the dunes flat and blocked out the Gulf of Mexico and a large number of stars with high-rise condominiums. You see them all along the coast, jammed into once perfect sand, a thumb in the eye of God. What I wanted was bay sand, river sand, colored by meandering miles of dark water, a place tourists are leery to wade. I wanted a place I could rent, steal or stow away on a boat.

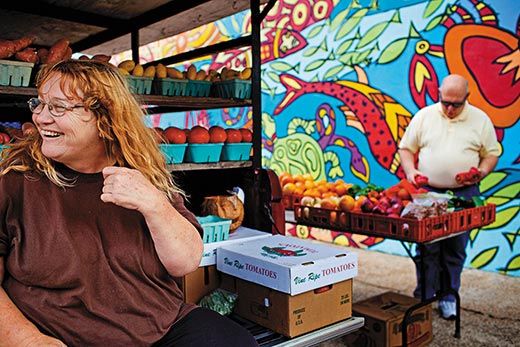

A town of about 17,000, Fairhope sits on bluffs that overlook the bay. It's not some pounded-out tortilla of a coastal town—all tacky T-shirt shops, spring break nitwits and $25 fried seafood platters—but a town with buildings that do not need a red light to warn low-flying aircraft and where a nice woman sells ripe cantaloupe from the tailgate of a pickup. This is a place where you can turn left without three light changes, prayer or smoking tires, where pelicans are as plentiful as pigeons and where you can buy, in one square mile, a gravy and biscuit, a barbecue sandwich, fresh-picked crabmeat, melt-in-your-mouth beignets, a Zebco fishing reel, a sheet of hurricane-proof plywood and a good shower head.

"Now, you have to look pretty carefully for a place on the coast to get the sand under your toes without somebody running over you with a Range Rover," said Skip Jones, who lives on the same bayfront lot, just south of Fairhope, his grandparents built on in 1939. "We may be gettin' to that point here, but not yet."

It would be a lie to say I feel at home here. It is too quaint, too precious for that, but it is a place to breathe. I have a rambling cypress house five minutes from the bay and a half-hour from the blue-green Gulf—even a big cow pasture near my house is closer to the waterfront than I am—but every day I walk by the water, and breathe.

It is, as most towns are, a little full of itself. Some people call it an artist's colony, and that is true, since you cannot swing a dead cat without hitting a serious-faced novelist. And there is money here, dusty money and Gucci money. There are shops where ladies in stiletto heels pay Bal Harbour prices for outfits that will be out of style before low tide, but these establishments can be fun, too. I like to stand outside the windows with paint on my sweat pants, tartar sauce on my T-shirt and see the shopgirls fret.

It had to change, of course, from the sleepy town it used to be, where every man, it seemed, knew the tides, when the air smelled from big, wet burlap bags of oysters and the only rich folks were those who came over on a ferry from Mobile to watch the sun set. But everybody is an interloper here, in a way. Sonny Brewer, a writer, came here in 1979 from Lamar County, in west central Alabama, and never really left. It was the late-afternoon sunlight, setting fire to the bay. "I was 30 years old," said Brewer. "I remember thinking, ‘God, this is beautiful. How did I not know this was here?' And here I stay."

It is the water, too. The sand is just a path to it.

Here are the black currents of Fish River, highways of fresh and salt water, big bass gliding above in the fresher water, long trout lurking below in the heavier, saltier depths. The Fish River empties into Weeks Bay, which, through a cut called Big Mouth, empties into Mobile Bay. Here, I caught a trout as long as my arm, and we cooked it in a skillet smoking with black pepper and ate it with roasted potatoes and coleslaw made with purple cabbage, carrots and a heaping double tablespoon of mayonnaise.

Here is the Magnolia River, one of the last places in America where the mail is delivered by a man in a boat, where in one bend in the river there is a deep, cold place once believed to have no bottom at all. You can see blue crabs the size of salad plates when the tides are right, and shrimp as big as a harmonica. Along the banks are houses on stilts or set far back, because the rivers flood higher than a man is tall, but the trees still crowd the banks, and it looks like something from The African Queen—or the Amazon.

Then, of course, there is the bay. You can see the skyscrapers of Mobile on a clear day, and at night you see a glow. I pointed to a yellow luminescence one night and proclaimed it to be Mobile, but a friend told me it was just the glow of a chemical plant. So now I tell people Mobile is "over yonder" somewhere.

You can see it best from the city pier, a quarter-mile long, its rails scarred from bait-cutting knives and stained with fish blood, its concrete floor speckled with scales. This is where Fairhope comes together, to walk, hold hands. It is here I realized I could never be a real man of the sea, as I watched a fat man expertly throw a cast net off the pier, at bait fish. The net fanned out in a perfect oval, carried by lead weights around its mouth, and when he pulled it in it was shining silver with minnows. I tried it once and it was like throwing a wadded-up hamburger sack at the sea.

So I buy my bait and feel fine. But mostly what I do here is look. I kick off my flip-flops and feel the sand, or just watch the sun sink like a ball of fire into the bay itself. I root for the pelicans, marvel at how they locate a fish on a low pass, make an easy half-circle climb into the air, then plummet into the bay.

I wonder sometimes if I love this so because I was born so far from the sea, in that red dirt, but people who have been here a lifetime say no, it is not something you get tired of. They tell you why, in stories that always seem to begin with "I remember..."

"I remember when I was about 10 years old, maybe 8, my mother and sisters and I went through Bon Secour and some guy in a little boat had caught a sawfish," said Skip Jones. "And I thought this thing can't be real—like I felt when they walked on the moon."

A lifetime later he is still looking in the water. "Last year I went out on the walk one morning at about 6 o'clock, and I looked down and there were a dozen rays, and I looked harder and they were all over the place, hundreds of them. Well, we have a lot of small rays, but these had a different, broader head. And I went inside and looked 'em up and saw that they were cownose rays that congregate around estuaries. I called my friend Jimbo Meador and told him what I saw, and he said, ‘Yeah, I saw them this morning.' They came in a cloud and then they were just gone. I don't know where. I guess to Jimbo's house."

I would like to tell people stories of the bay, the rivers, the sea, tell them what I remember. But the best I can do is a story about cows. I was driving with my family to the bay, where a bookseller and friend named Martin Lanaux had invited us to watch the Fourth of July fireworks from his neighborhood pier. As we passed the cow pasture, the dark sky exploded with color, and every cow, every one, it seemed, stood looking up at it. It was one of the nicer moments in my life, and I didn't even get my feet wet.

Rick Bragg is the author of The Prince of Frogtown, now in paperback, All Over but the Shoutin' and Ava's Man.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.