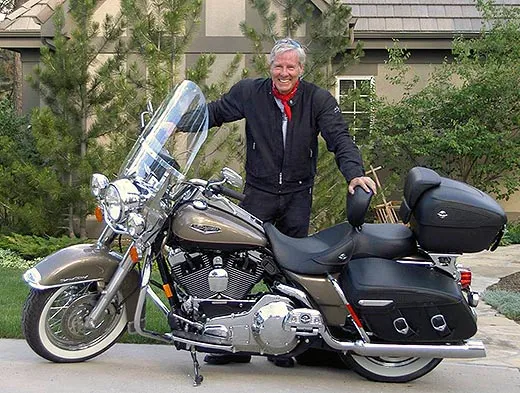

Finding America’s Heart by Harley

Wealthy businessman John Gussenhoven pledged his fortunes to assist those who helped him on his journey across America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/John-Gussenhoven-Harley-Davidson-631.jpg)

Carl Snow speaks in that reassuring country baritone you tend to associate with seasoned airline captains. That’s only fitting, since he has flown jets for some 40 years now and has trained his share of the aspiring pilots who flock to his hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma, for flight instruction. So when a steady, understated gentleman like Carl Snow tells you that about the best aviation student he ever taught was a middle-aged insurance executive named John Gussenhoven, you take him at his word. “John’s a quick study,” Snow says. “I never had to tell him anything more than once.”

By any reckoning, Gussenhoven, 63, is a most unusual man. Though he’s modest about his accomplishments, it’s clear that when he sets a goal, he generally gets there. A collegiate lacrosse and soccer star and U.S. Army veteran, Gussenhoven not only learned to fly at a comparatively advanced age, he achieved the top level of FAA certification, Airline Transport Pilot, in just three-and-a-half years. He was a high flyer in business, too, rising to partner at Johnson & Higgins, the 150-year-old insurance brokerage and consulting outfit that was bought by Marsh & McLennan in 1997 for $1.8 billion. An expert free climber, sailor and skier, Gussenhoven even took up ballroom dancing three months ago (“I hated it as a kid,” he says). He has already won two competitions. His drive to excel stems from his “stubborn, single-minded, Dutch-inherited personality,” Gussenhoven suggests.

For all that, Gussenhoven felt there was an important check mark missing from his life’s to-do list. Born in Mexico City, the son of a General Motors executive who planted the company flag in several Latin American markets during the 1930s, Gussenhoven didn’t arrive in the U.S. until he was 14. Even five years ago, he says, he knew squat about the so-called flyover country between the East and West coasts. So he set about correcting that deficiency with typical Gussenhovian zeal. He bought a Harley-Davidson Road Master King, learned to ride it proficiently, and then marked his route with a bold “X” across a map of the 48 states. “My purpose,” he says simply, “was to discover my own country, which I had never really seen.”

He carried out the plan in 2005 and 2006, hurtling through 27 states in two-week segments a year apart. The first leg took him from the Seattle area down to Naples, Florida, where he keeps one of his three homes (the others being in Wilmington, North Carolina, and Jackson Hole, Wyoming). The second stroke of the “X” began in San Diego and culminated in Eastport, Maine. Gunning a hog cross-country means navigating mountain passes and deserts and braving unfriendly weather, but Gussenhoven made sure to sleep in clean beds, eat regularly and check in with his wife, Harriette, and son, Jordan. He kept a detailed log, documenting, for instance, that he traveled exactly 8,556.5 miles along the twin vectors, which criss-crossed near Mullinsville, Kansas at precisely 3:34:22 p.m. on May 21, 2006.

Gussenhoven also took some 3,000 photographs and recorded the GPS waypoints for each. He furnished the information to aerial photographer Jim Wark, who retraced the identical routes, snapping some 6,000 photos from his single-engine Aviat Husky, which looks something like Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis. “The way Jim worked was to take that little fabric plane, stick the rudder between his legs, open the window and the door and turn the plane on its side with his knees,” Gussenhoven says. “Then he’d just lean out with his Leica camera and take pictures.”

The result of their exceptional collaboration is Crisscrossing America, a handsome coffee-table book reaffirming that from the highway or the skyway, this is still a land of splendor. Gussenhoven did find some things that disturbed him: the roads and bridges in disrepair; the contrast between downtrodden laborers at the Mexican border and luxurious Palm Springs; the abandonment of Main Street culture in favor of ugly strip malls and highway bypasses. But he was more often inspired by the sense of freedom and possibility he found on the open road. The book’s cover photograph shows his bike parked on the shoulder of a highway that disappears into the vast, tawny plains of northeastern New Mexico. To Gussenhoven, the scene was an epiphany. “I can’t tell you how many times I sang ‘America the Beautiful’ after I took that picture,” he says. “Apart from the truck coming down the road, this was my country. I was solitary, but I felt very much at home, secure and at peace. It had just rained, the air was clean. It was a sweet sort of fragrance, and I couldn’t have been happier. It set off millions of synapses in my brain that said, ‘You know, you should be doing more and more and more of this.’”

***

As he traveled, Gussenhoven often received the drooped left-hand bikers’ greeting from fellow riders. This became an emblem of his other great discovery: the openhearted kindness he experienced across the nation. “These friendly people did not treat me differently because of my background, race, education, or appearance,” he writes of a couple that insisted he join them for dinner in Santa Fe. “They did so, I suspect, because they saw someone who perhaps needed companionship and conversation.”

Spurred by the goodness and generosity he encountered, and by the sudden death of his beloved twin sister, Nini, just shy of their 60th birthday in 2006, Gussenhoven established the Crisscrossing America Trust that year to make helpful gifts to people who might appreciate an unexpected boost. All proceeds from the book will be directed to the trust, which quietly distributes a couple of dozen grants a year, mostly in the $1000 to $5000 range. “The foundation is a beautiful testament to his love and commitment to his sister and his family,” says Ward “Tree” Roundtree, a retired California teachers’ union official, who met Gussenhoven in Laramie, Wyoming.

Roundtree was riding east from Oakland with members of the Iron Souls Motorcycle Club to attend Rolling Thunder, the annual rally of Vietnam vets in Washington, D.C. They happened to pull into the parking lot of a Comfort Inn at the same time as Gussenhoven. “We were going to have dinner, and I suggested that he join us—weary travelers just having a good time together, talking about life and the ride,” Roundtree recalls. “We struck up a very fast friendship.” For Roundtree, it was a normal gesture. For Gussenhoven, to be immediately embraced by four strangers from clear across the country was a revelation. As they unwound, the Bay Area cyclists told him about their involvement with Mother Mary Ann Wright, known as the “Mother Theresa of Oakland”—a woman who provided three meals a day to hundreds of homeless people in her community for decades, receiving no pay. The trust’s first check supported the Mother Mary Ann Wright Foundation, which has continued her mission after her death at 87 in May 2009.

Other beneficiaries of the trust include a former smokejumper who had developed asthma; a Florida woman who was working two jobs to support her dream of attending nursing school; and a young dance teacher who dedicates herself to helping kids succeed in after-school programs in a very tough middle-school environment. All were people who had befriended Gussenhoven along the line.

***

Perhaps the best illustration of Gussenhoven’s quiet support comes from his old flying teacher from Tulsa, Carl Snow. The gesture was so moving that neither talks about it without choking up.

Snow’s parents came up during the Depression, which hit Oklahomans harder than most. They found work during the war at Douglas Aircraft in Tulsa, which was churning out B-24 bombers. “One worked on the day shift, one on the night shift—they would pass each other, coming and going—so I’m not sure how I ever got here,” Snow says, chuckling. But they were proud to do their part. Snow’s father had security clearance to work on the plane’s top-secret Norden bombsight, and he had some good times, too. “He would talk fondly about how the fellas would shoot craps in the middle of the night in the belly of this B-24 that they were building, out on the ramp, in the rain,” Snow says.

Snow knew he wanted to fly planes from the age of six. By his early 20s, he was already landing Lear jets in dangerous oil exploration sites like the North Slope of Alaska. He had aviation in his blood, and developed what he calls “warbird fever,” a love of World War II aircraft and history.

He lost his mother to Alzheimer’s in 1989 after a five-year battle “that just about brought me to my knees,” Snow says. “I thought, I can only do one of these. I got about a six-to eight year break before Dad developed Parkinson’s disease and I had to do a five-year downhill run with him.”

The Depression left a mark on a lot of men of his father’s generation, Snow says. “They’re hard, hard, hard. They somehow got through that by just being gut-hard. They’re not going to tell you they loved you. The only time I ever hugged my dad was the night Mom passed away, and I got there first, so when he got there I hugged him and told him she was gone. And so, because Dad had that toughness about him as he went down, it was really hard to manage. He was fighting the disease, he was fighting having to do things he didn’t want to do, and it created some unpleasant memories.”

Gussenhoven understood; he had recently lost his own dad, and he knew how important it was to focus on the good memories, and try to put the painful ones behind you. He thought for a long time about what he might do to help his friend. And he hatched a plan.

He called an outfit called the Commemorative Air Force, and asked them if they had a B-24 somewhere. Turned out they had one that toured at air shows, and it just happened to be Riverside Airport, near Snow’s residence in Bixby, just south of Tulsa. So John made arrangements for Carl and his family to walk out on the tarmac and be greeted by the B-24 crew. That’s what he told Carl. But there was more to it.

The crew invited the Snow family aboard for what promised to be a quick takeoff and landing in the historic plane, Carl remembers. “But pretty quick it became apparent that, well, we weren’t just going around the airport traffic pattern, because we’ve left the pattern. Then the pilot invites me to get up and get in the front seat, and it’s dawning on me that this is not going to be a five-minute deal. We’re goin’ flying.”

They were headed for Memorial Park, where Snow’s parents had both been laid to rest. Carl realized, though, that the cemetery lies right under the final flight path, landing north, of Tulsa International Airport. Some special arrangements must have been made. “With John involved, there’s no telling,” he thought. And indeed, air traffic let them do exactly what they wanted to do, which was make a couple of low-level passes over the cemetery. It was then that Carl Snow got to dip the wing of the B-24 in one final, traditional salute to his mom and dad.

They remained aloft for a good 45 minutes, even allowing Carl’s son Garrett, also a skilled pilot, to take control of the plane. People on the ground must have stared in wonderment, though some of the old-timers would certainly have recognized it. “The sound of a B-24 is unique, the silhouette is unique,” Snow says.

He can’t even begin to express his gratitude to John Gussenhoven for having the sensitivity and imagination to orchestrate something like this.

“How would you even think of a thing like this? And even if you thought of it, how would you go about making it happen? That’s John’s human touch. That’s what really motivates him, what drives him.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jamie-Katz-240.jpg)