Finding Serenity on Japan’s San-in Coast

Far from bustling Tokyo, tradition can be found in contemplative gardens, quiet inns and old temples

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Hagi-castle-Shizuki-Park-631.jpg)

At the Buddhist temple of Gesshoji, on the western coast of Japan, the glossy, enormous crows are louder—much louder—than any birds I have ever heard. Crows are famously territorial, but these in the small city of Matsue seem almost demonically possessed by the need to assert their domain and keep track of our progress past the rows of stone lanterns aligned like vigilant, lichen-spotted sentinels guarding the burial grounds of nine generations of the Matsudaira clan. The strident cawing somehow makes the gorgeous, all-but-deserted garden seem even further from the world of the living and more thickly populated by the spirits of the dead. Something about the temple grounds—their eerie beauty, the damp mossy fragrance, the gently hallucinatory patterns of light and shadow as morning sun filters through the ancient, carefully tended pines—makes us start to speak in whispers and then stop speaking altogether until the only sounds are the bird cries and the swishing of the old-fashioned brooms a pair of gardeners are using to clear fallen pink petals from the gravel paths.

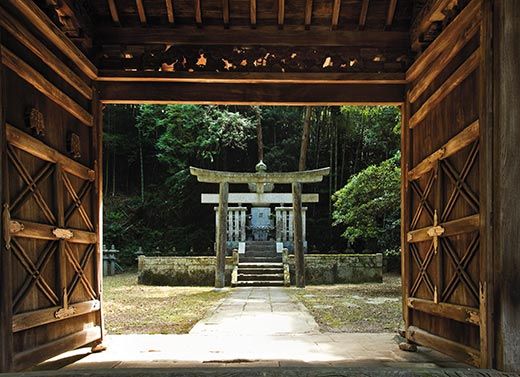

Gesshoji dates from the late 17th century, when an older structure—a ruined Zen temple—was turned into a resting place for the Matsudaira aristocracy, which would rule this part of Japan for more than 200 years. Successive generations of aristocrats added on to the complex, eventually producing a maze of raised mounds and rectangular open spaces, like adjacent courtyards. Each grave area is reached through an exquisitely carved gate, decorated with the images—dragons, hawks, calabashes, grapefruits and flowers—that served as the totems of the lord whose tomb it guards. Ranging from simple wooden structures to elaborate stone monuments, the gates provide a kind of capsule history of how Japanese architecture evolved over the course of centuries.

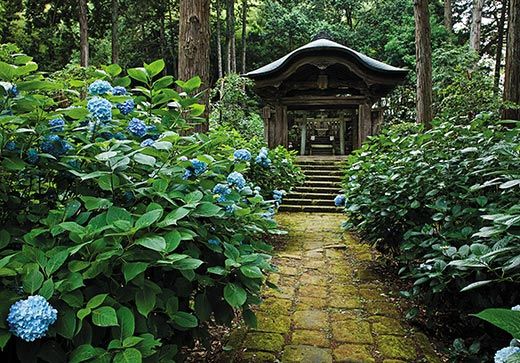

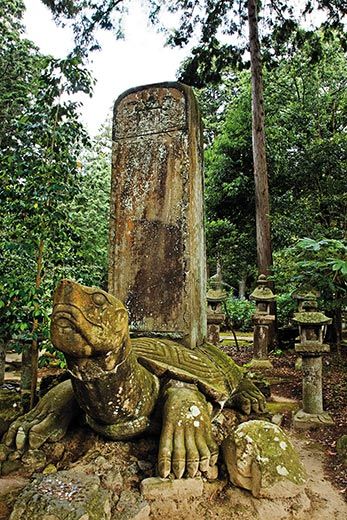

On the April morning when my husband, Howie, and I visit Gesshoji, the cherry blossoms are just beginning to drop from the trees. The pointed foliage in the iris bed promises an early bloom, and the temple is celebrated for the 30,000 blue hydrangeas that will flower later in the season. It is also famous for the immense statue of a ferocious-looking tortoise, its reptilian head raised and telegraphing a fierce, rather untortoiselike alertness, positioned in front of the tomb of the sixth Matsudaira lord. According to one superstition, rubbing the turtle's head guarantees longevity, while another claims that, long ago, the beast lumbered off its stone slab each night, crawled through the gardens to drink water from the pond and wandered through the city. The tall stone pillar that rises from the middle of its back was put there, it is said, to discourage the turtle's nightly strolls.

Leaving the temple, I see a sign, noting that the writer Lafcadio Hearn was especially fond of the temple and that he wrote about the tortoise. The quote from Hearn, which the sign reproduces in part, begins with a description of certain sacred statues reputed to have a clandestine nocturnal life: "But the most unpleasant customer of all this uncanny fraternity to have encountered after dark was certainly the monster tortoise of Gesshoji temple in Matsue....This stone colossus is almost seventeen feet in length and lifts its head six feet from the ground.... Fancy...this mortuary incubus staggering abroad at midnight, and its hideous attempts to swim in the neighbouring lotus-pond!"

Sometime in the early 1970s I saw a film that so haunted me that for years I wondered if I might have dreamed it. It didn't help that I could never find anyone else who had seen it. The film was called Kwaidan, and, as I later learned, was directed by Masaki Kobayashi, based on four Japanese ghost stories by Hearn. My favorite segment, "Ho-ichi the Earless," concerned a blind musician who could recite the ballad of a historic naval battle so eloquently that the spirits of the clan members killed in the fighting brought him to the cemetery to retell their tragic fate.

Subsequently, I grew fascinated by the touching figure of the oddly named writer whose tales had provided the film's inspiration. The son of a Greek mother and an Irish father, born in Greece in 1850, Hearn grew up in Ireland. As a young man, he emigrated to Ohio, where he became a reporter for the Cincinnati Enquirer—until he was fired for marrying a black woman. The couple ended the marriage, which had never been recognized, and he spent ten years reporting from New Orleans, then two more in Martinique. In 1890, he moved to Japan, about which he intended to write a book and where he found work as a teacher at a secondary school in Matsue.

Tiny in stature, nearly blind and always conscious of being an outsider, Hearn discovered in Japan his first experience of community and belonging. He married a Japanese woman, assumed financial responsibility for her extended family, became a citizen, had four children and was adopted into another culture, about which he continued to write until his death in 1904. Though Hearn took a Japanese name, Yakumo Koizumi, he saw himself as a foreigner perpetually trying to fathom an unfamiliar society—an effort that meant paying attention to what was traditional (a subject that fed his fascination with the supernatural) and what was rapidly changing. Though his work has been criticized for exoticizing and romanticizing his adopted country, he remains beloved by the Japanese.

I had always wanted to visit the town where Hearn lived for 15 months before career and family obligations led him to move elsewhere in Japan, and it seemed to me that any impression I might take away about the traditional versus the modern, a subject of as much relevance today as it was in Hearn's era, might begin in the place where Hearn observed and recorded the way of life and the legends that were vanishing even as he described them.

In the weeks before my departure, friends who have made dozens of trips to Japan confess that they had never been to the San-in coast, which borders the Sea of Japan, across from Korea. The relative scarcity of Western visitors may have something to do with the notion that Matsue is difficult or expensive to reach, a perception that is not entirely untrue. You can (as we did) take an hour-and-a-half flight from Tokyo to Izumo, or alternately, a six-hour train journey from the capital. When I tell a Japanese acquaintance that I am going to Matsue, he laughs and says, "But no one goes there!"

In fact, he couldn't be more wrong. While the area is mostly unexplored by Americans and Europeans, it's very popular with the Japanese, many of whom arrange to spend summer vacations in this region known for the relatively unspoiled, rugged beauty of its shoreline and the relaxed pace and cultural riches of its towns. It offers a chance to reconnect with an older, more rural and traditional Japan, vestiges of which still remain, in stark contrast to the shockingly overdeveloped and heavily industrialized San-yo coast, on the opposite side of the island. The Shinkansen bullet train doesn't reach here, and a slower private railroad line wends its way up a coast that features dramatic rock formations, white beaches and (at least on the days we visited) a calm turquoise sea. During the tourist season, it's even possible to travel through part of the area on a steam locomotive.

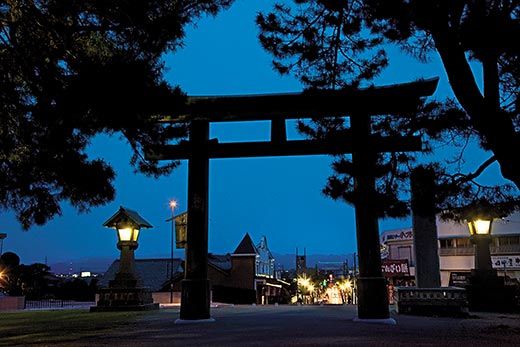

Shimane Prefecture, at the heart of the San-in region, is the site of several celebrated religious shrines. The most important of these is Izumo-taisha, a few miles from Izumo. One of the oldest (its date of origin is unclear, though it is known to have existed in the eighth century), largest and most venerated pilgrimage destinations in the country, Izumo-taisha is where, it is believed, eight million spirit gods congregate for their official annual conference, migrating from all over Japan every October; everywhere except Izumo, October is known as the month without gods, since they are all presumably in Izumo, where October is called the month with gods.

Izumo-taisha is dedicated to Okuninushi, a descendant of the god and goddess who created Japan, and the deity in charge of fishing, silkworm culture and perhaps most important, happy marriages. Most likely, that explains why on a balmy Sunday afternoon the shrine—which consists of several structures surrounded by an extensive park—is crowded with multi-generational families and with a steady stream of ever-so-slightly anxious-looking couples who have come to admire the cherry blossoms and ask the gods to bless their unions.

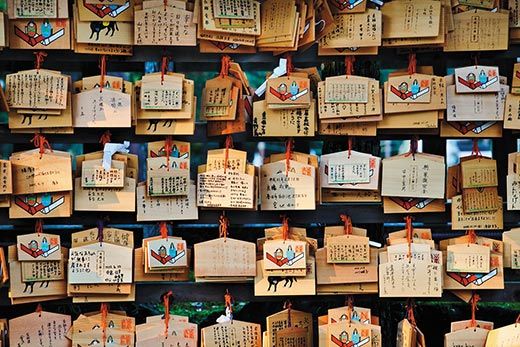

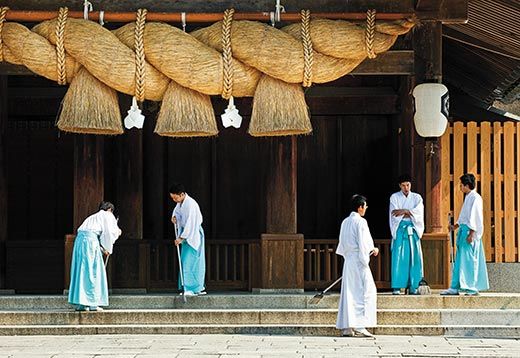

As at every Shinto shrine, the faithful begin by symbolically purifying themselves, washing their hands and rinsing their mouths with water poured from delicate dippers hung above a trough. Then, approaching the main hall, they clap their hands to attract the attention of the gods, and bow to express respect. Some clap twice, others four times because four was the sacred number in ancient Japan; it was thought that both gods and people had four types of souls. It takes a certain amount of concentration for these newlyweds-to-be to focus on their heartfelt prayers while, all around them, people—children especially—are excitedly flinging coins into the air, trying to lodge them (doing so successfully is said to bring good fortune) in the huge, elaborately coiled straw ropes that guard the entrance to the central buildings. These ropes, thought to prevent unwelcome visitations from evil spirits, are characteristic of Shinto shrines, but the colossal ones at Izumo-taisha are unusually imposing.

In Izumo, a helpful young woman who tells us where to stow our luggage provides our first introduction to the patient sweetness with which the Japanese try to aid foreigners, even if it means locating the one person in the building—or the town—who speaks a little English, all of which makes traveling in this comparatively out-of-the way region easier and more fun than (as I had worried) daunting. From Izumo City, it's less than a half-hour by train, past farmhouses and kitchen gardens, to Matsue. The so-called "City of Water," bordered by the Tenjin River and by Lake Shinji, which is famous for its spectacular sunsets, Matsue also has an extensive system of moats surrounding its 17th-century castle. On clear days, a sparkly aquatic light blends the pinkish aura of Venice with the oceanic dazzle of the Northern California coast.

A 15-minute taxi ride from downtown Matsue is Tamatsukuri Onsen, the hot spring resort where we are staying and where the gods are said to enjoy an immersion in the healing waters. Running through this bucolic suburb is the Tamayu River, edged on both sides by blossoming cherries that shade groups of family and friends picnicking on the peacock-blue plastic tarps that are de rigueur for this 21st-century version of the ancient custom of cherry-blossom viewing.

The most familial, genially celebratory version of this time-honored custom is transpiring on the grounds of Matsue Castle on the late Sunday afternoon we visit. Lines of brightly colored stands sell toys, trinkets, masks, grilled squid and fried balls of dough stuffed with octopus. The most popular stalls offer still-warm egg cookies (shaped a bit like madeleines) and freshly baked bean-paste dumplings, playing to the (somewhat mystifying, to me) Japanese passion for what one might call extreme sweets. Meanwhile, on a shaded platform, a flute and shamisen orchestra produces the rippling phrases of classical Japanese music.

Matsue Castle rises like a stone wedding cake, its monumental walls supporting a series of terraced gardens. On its northern slope is a wooded park meticulously groomed to create the impression of untouched wildness. At the top of the hill is the castle itself, an ornate, harmonious, stately structure rising five stories and built in a fashion known as the "plover" style for its roofs, which rising to steep peaks and curving outward and upward, suggest the spread wings of a shorebird.

The castle is one of those places that make me wish I knew more (or to be truthful, anything at all) about carpentry, so that I could properly appreciate the craftsmanship that enabled the structure to be built without nails, assembled by artful joinery in what must be the supreme incarnation of tongue-and-groove construction. I can only admire the burnished richness of the wooden siding; the art objects, samurai helmets, antique kimonos; the historical murals and architectural models in the castle museum; and the vertiginous view of the distant mountains from the open platform on the highest floor.

Our capable companion, Chieko Kawasaki—many of the smaller Japanese cities and towns provide volunteer English-speaking guides through the municipal tourist bureaus, if you contact them in advance—explains the many superstitions associated with the castle. According to one, construction was plagued by problems until workers discovered a skull pierced by a spear; only after the skull was given a proper ceremonial burial did the building proceed smoothly. And as we stand on the top level, looking out over Lake Shinji, Chieko tells us that the island in the middle of the lake—Bride Island—is believed to have sprung up when a young wife, mistreated by her mother-in-law, decided to return to her family via a shortcut over the frozen lake. When the ice melted unexpectedly and she fell through and drowned, a goddess took pity on her and turned her into an island.

As Chieko speaks, I find myself thinking again of Lafcadio Hearn, and of the delight he took in hearing—and recording—such stories. In his essay "The Chief City of the Province of the Gods," Hearn repeats the tale, which he calls "The Island of the Young Wife." His summary is an abbreviated version of what Chieko has just told us. Perhaps the myth has continued to evolve and grow over the intervening decades, and perhaps it is as alive today as it was in Hearn's time, and in the centuries before that.

Hearn's former house and the museum next door, at the base of the castle hill, are located in an old samurai neighborhood. At the Hearn Museum, as at Izumo-taisha, we again find ourselves among pilgrims. Only this time they are fellow pilgrims. A steady parade of Japanese visitors files reverently past vitrines containing a range of memorabilia, from the suitcase Hearn carried with him to Japan to handsome copies of first editions of his books, photographs of his family, his pipes and the conch shell with which he allegedly called his servants to relight his pipe, letters in his idiosyncratic handwriting and tiny cages in which he kept pet birds and insects. What seems to inspire particular interest and tenderness among his fans is the high desk that Hearn had specially made to facilitate reading and writing because he was so short and his vision so poor (one eye had been lost in a childhood accident). Beginning writers everywhere might take a lesson from Hearn's working method: when he thought he was finished with a piece, he put it in his desk drawer for a time, then took it out to revise it, then returned it to the drawer, a process that continued until he had exactly what he wanted.

Hearn's image is everywhere in Matsue; his sweet, somewhat timid and melancholy mustachioed face adorns lampposts through the city, and in souvenir shops you can even purchase a brand of tea with his portrait on the package. It is generally assumed that Hearn's place in the heart of the Japanese derives from the fervor with which he adopted their culture and attempted to make it more comprehensible to the West. But in his fascinating 2003 book about the relationship between 19th-century New England and Japan, The Great Wave, literary critic and historian Christopher Benfey argues that Hearn, who despised the bad behavior of foreign travelers and deplored the avidity with which the Japanese sought to follow Western models, "almost alone among Western commentators...gave eloquent voice to...Japanese anger—and specifically anger against Western visitors and residents in Japan."

"Hearn," notes Benfey, "viewed Japan through an idealized haze of ghostly ‘survivals' from antiquity." Fittingly, his former residence could hardly seem more traditionally Japanese. Covered in tatami mats and separated by sliding shoji screens, the simple, elegant rooms are characteristic of the multipurpose, practical adaptability of Japanese homes, in which sitting rooms are easily converted to bedrooms and vice versa. Sliding back the outer screens provides a view of the gardens, artful arrangements of rocks, a pond, a magnolia and a crape myrtle, all of which Hearn described in one of his best-known essays, "In a Japanese Garden." The noise of the frogs is so perfectly regular, so soothing, so—dare I say it?—Zenlike that for a moment I find myself imagining (wrongly) that it might be recorded.

In his study, Hearn worked on articles and stories that got steadily less flowery (a failing that dogged his early, journalistic prose) and more evocative and precise. In "The Chief City of the Province of the Gods," Hearn wrote that the earliest morning noise one hears in Matsue is the "pounding of the ponderous pestle of the kometsuki, the cleaner of rice—a sort of colossal wooden mallet....Then the boom of the great bell of Zokoji, the Zenshu temples," then "the melancholy echoes of drumming...signaling the Buddhist hour of morning prayer."

These days, Matsue residents are more likely to be awakened by the noise of traffic streaming along expressways bordering the lake. But even given the realities of contemporary Japan, it is surprisingly easy to find a place or catch a glimpse of something that—in spirit, if not in precise detail—strikes you as being essentially unchanged since Hearn spent his happiest days here.

One such site is the Jozan Inari Shrine, which Hearn liked to pass through on his way to the school at which he taught. Located not far from the Hearn Museum, in the park at the base of Matsue Castle, the shrine—half-hidden amid the greenery and a bit difficult to find—contains thousands of representations of foxes, the messengers of the god (or goddess, depending on how the deity is represented) Inari, who determines the bounty of the rice harvest and, by extension, prosperity. Passing through a gate and along an avenue of sphinxlike foxes carved in stone, you reach the heart of the shrine, in a wooded glade crowded with more stone foxes, pitted by weather, covered with moss, crumbling with age—and accompanied by row after row of newer, bright, jaunty-looking white and gold ceramic foxes. Inari shrines, which have become increasingly popular in Japan, are thought by some to be haunted and best avoided after dark. When we reach the one in Matsue, the sun is just beginning to set, which may be part of the reason we are all alone there. With its simultaneously orderly and haphazard profusion of foxes, the place suggests those obsessional, outsider-art masterpieces created by folk artists driven to cover their homes and yards with polka dots or bottles or buttons—the difference being that the Inari Shrine was generated by a community, over generations, fox by fox.

It's at points like this that I feel at risk of having fallen into the trap into which, it is often claimed, Hearn tumbled headlong—that is, the pitfall of romanticizing Old Japan, the lost Japan, and ignoring the sobering realities of contemporary life in this overcrowded country that saw a decade of economic collapse and stagnation during the 1990s and is now facing, along with the rest of us, yet another financial crisis.

Our spirits lift again when we reach Hagi. Though the population of this thriving port city on the Sea of Japan, up to five hours by train down the coast from Matsue, is aging, the city seems determined to preserve its history and at the same time to remain vital and forward-looking, to cherish what Hearn would have called the "savings" of an older Japan and to use what remains of the past to make life more pleasurable for the living. So the ruins of Hagi Castle—built in 1604 and abandoned in the late 19th century—have been landscaped and developed into an attractive park enjoyed by local residents.

Long established as a center for pottery, Hagi has nurtured its craftsmen, and is now known for the high quality of the ceramics produced here and available for sale in scores of studios, galleries and shops. Hagi boasts yet another lovingly restored samurai district, but here the older houses are surrounded by homes in which people are still living and tending the lush gardens that can be glimpsed over the whitewashed walls. Sam Yoshi, our guide, brings us to the Kikuya residence, the dwelling of a merchant family dating from the early 17th century. Perhaps the most complex and interesting of the houses we've visited in this part of Japan, the Kikuya residence features a striking collection of domestic objects (from elaborate hair ornaments to an extraordinary pair of screens on which a dragon and tiger are painted) and artifacts employed by the family in their business, brewing and selling soy sauce. Yasuko Ikeno, the personable docent who seems justifiably proud of the antiquity and beauty of the Kikuya house, demonstrates an ingenious system that allows the sliding outside doors—designed for protection against the rain—to pivot around the corners of the building. She also takes us through the garden in which, as in many Japanese landscapes, the distance of just a few paces radically changes the view, and she encourages us to contemplate the flowering cherries and ancient cedars.

Our visit to Hagi culminates at the Tokoji temple, where the young, charismatic Buddhist abbot, Tetsuhiko Ogawa, presides over a compound that includes a burial ground reminiscent of the one at Gesshoji. The crows, I can't help noticing, are almost as loud as those in Matsue. But the temple is far from deserted, and while rows of the stone lanterns attest to the imminence of the dead, in this case the Mouri clan, the living are also very much in evidence. In fact, the place is quite crowded for an ordinary weekday afternoon. When I ask the abbot what constitutes a typical day in the life of a Buddhist priest, he smiles. He wakes at dawn to pray, and prays again in the evening. During the rest of the day, though, he does all the things other people do—grocery shopping, for example. And he devotes a certain amount of time to comforting and supporting the mourners whose loved ones are buried here. In addition, he helps arrange public programs; each year the city stages a series of classical chamber music concerts within the temple precincts.

As it happens, it's not an ordinary afternoon after all. It's the Buddha's birthday—April 8. A steady procession of celebrants have come to honor the baby Buddha by drinking sweet tea (the abbot invites us to try some—it's delicious!) and by pouring ladles of tea over a statue of the deity. While we are there, Jusetsu Miwa, one of Hagi's most famous potters, arrives, as he does each year on this date, to wish the Buddha well.

Just before we leave, Tetsuhiko Ogawa shows us a wooden bell, carved in the form of a fish, that is traditionally used at Zen temples to summon the monks to meals. In the mouth of the fish is a wooden ball that symbolizes earthly desires, and striking the bell, the abbot tells us, causes the fish (again, symbolically) to spit out the wooden ball—suggesting that we too should rid ourselves of our worldly longings and cravings. As the sound of the bell resonates over the temple, over the graves of the Mouri clan, over the heads of the worshipers come to wish Buddha a happy birthday, and out over the lovely city of Hagi, I find myself thinking that the hardest thing for me to lose might be the desire to return here. Even in the midst of travel, I have been studying the guidebooks to figure out how and when I might be able to revisit this beautiful region, this welcoming and seductive melding of old and new Japan, where I understand—as I could not have before I came here—why Lafcadio Hearn succumbed to its spell, and found it impossible to leave the country, where, after a lifetime of wandering, he at last felt so fully at home.

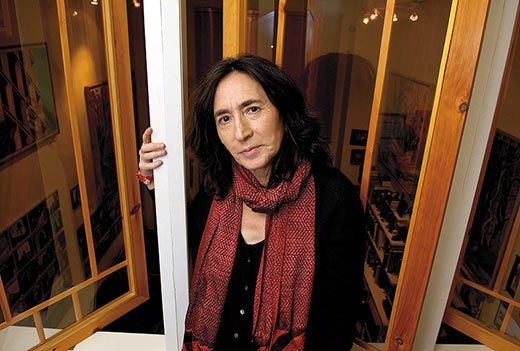

Francine Prose's 20th book, Anne Frank: The Book, The Life, The Afterlife, will be published this month. Photographer Hans Sautter has lived and worked in Tokyo for 30 years.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.