After a rollercoaster 15 months of sudden closures and dismal occupancy rates, hotels across the United States are cautiously greeting travelers again thanks to a string of creative measures, with once-exotic technological novelties like laser temperature guns, HVAC filters and UV sterilizer wands now standard issue. But it's worth remembering that America's most famous hotels have survived crises other than Covid-19. The hospitality industry has had to adapt to wars, economic spirals, radical fashion changes—and yes, other, even more devastating epidemics—each of which forced somersaults that give new meaning to the contemporary buzzword "pivot."

The Spirit of 1906: Fairmont Hotel San Francisco

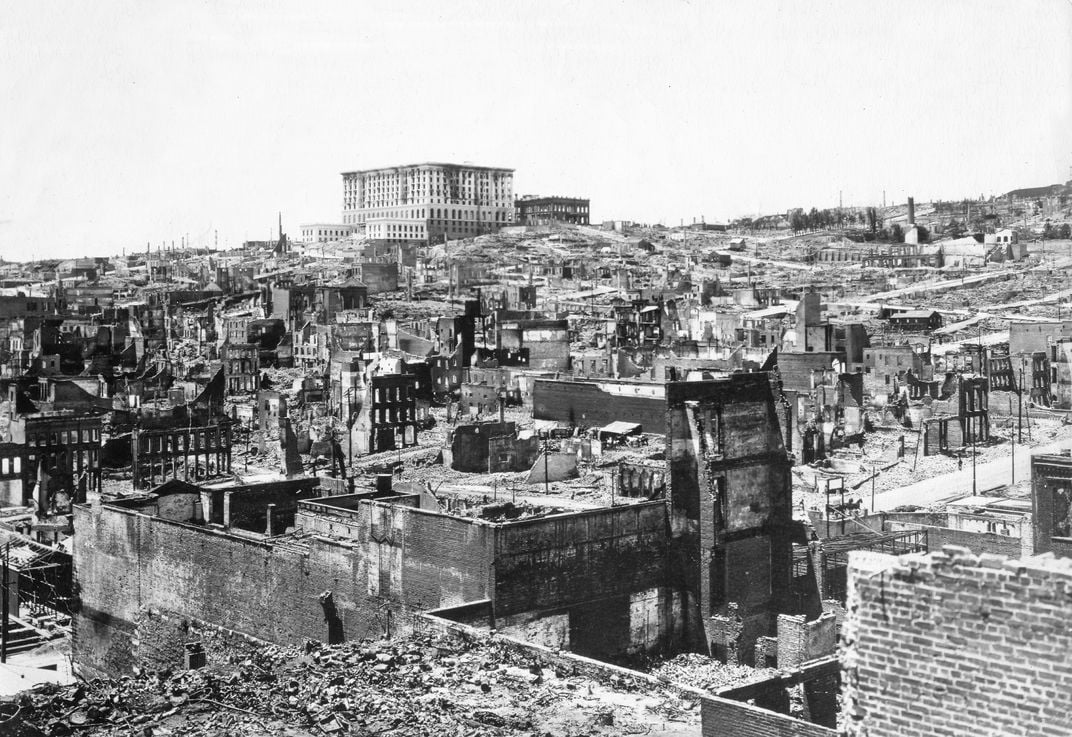

In the early morning of April 18, 1906, when San Franciscans staggered into the streets after one the most devastating earthquakes of U.S. history—it hit at 5:12 a.m.—several of its most luxurious hotels were still standing. Then came the aftermath: the fires that raged for three days and wiped out about 80 percent of the city. The most lavish newcomer, the Fairmont—perched in aristocratic glory high on the swank Nob Hill, with panoramic views over the city and glittering harbor—had been almost completed and was getting ready to open its gilded doors when the double disasters hit. Somehow the structure remained standing even though much of it had caught fire. A photograph taken from a balloon over the city about seven weeks later shows it sitting like a singed jewel box, with the charred and desolate streets all around as if they had been bombed. (The Palace Hotel, a favorite of visiting royalty, was not so lucky; a total ruin, it had to be rebuilt from scratch. The tenor Enrico Caruso, who was a guest at the time, escaped clutching a signed photograph of President Teddy Roosevelt and fled the city).

Still, while the Fairmont's majestic edifice survived, the interior damage was extensive. Many of the marble columns in the lower floors had buckled, and the burned-out upper floors were so twisted and contorted that photographs from the time evoke a funhouse mirror maze. Still, the crisis provoked innovation. Although male experts said the hotel should be leveled, the owners (three wealthy sisters who named the hotel after their father, James Graham Fair, a U.S. Senator and mining baron) hired one of America's first female architects and engineers, Julia Hunt Morgan, to repair it using reinforced concrete—a then little-known material that could resist future seismic activity.

Morgan's efficient work allowed the Fairmont to reopen only a year after the disaster, in April 1907. "It was like the Phoenix rising from the ashes," says the Fairmont's spokesperson and history buff, Michelle Heston, of the glamorous opening gala, which attracted the cream of Californian society as well as scions from the East Coast who were invited across the country in luxury Pullman trains. "It was a formal announcement that San Francisco was back on its feet."

The achievement won Morgan the admiration of William Randolph Hearst, among others, who hired her to design his famous "Castle" in San Simeon. Today the hotel continues to preside over San Francisco, having become a cultural presence in the city on every level. In 1945, for example, it hosted the key meetings that would lead to the foundation of the United Nations—and in the same year, opened the Bay area's most beloved tiki bar, the Tonga Room and Hurricane Bar.

1918: Mohonk vs. the Spanish Flu

The wood-paneled corridors and fantastical spires of Mohonk Mountain House evoke a lost age of Victorian gentility, but a tinted postcard on display in the New Paltz, New York resort's spa is jarringly contemporary: It shows holidaymakers at the golf link, all wearing masks over their noses and mouths, including the jaunty young caddie; only the sportsman about to take a swing is bare-faced. There is no doubt that it dates from 1918, when the Spanish flu, the world's deadliest epidemic, was wreaking havoc across the United States.

Founded by Quakers in the Hudson Valley in 1869, the venerable Mohonk has survived crises most of us are only dimly aware of today. (The 1893 economic crash, anyone?) But few disasters posed such challenges for America's early hospitality industry as the so-called Spanish flu. (Nobody knows the death toll, but it was probably between 20 to 50 million worldwide—compared to 17 million killed in World War I. The virus was unfairly called "Spanish" because Spain, as a rare neutral country, openly reported its ravages in the press, while most of Europe and the U.S. were locked under censorship; epidemiologists today prefer to call it "H1n1.") Mohonk's isolated natural setting, nestled by a pristine, cliff-lined lake on the wild Shawangunk Ridge, helped it through the crisis. Its guests, who generally holed up in the resort for months at a time, dodged cases through the spring and summer of 1918, when the epidemic was at its worst in New York City, 90 miles south. The first seven cases at the resort were only registered in late October, just before Mohonk traditionally closed for the winter. All were quarantined.

That October, the prospects for the 1919 season were daunting, to say the least, but Mohonk's owners, the Smiley family, sent an optimistic message in the hotel's weekly bulletin: “That next season may open in a greatly changed world, we fervently hope. If, however, a shadow still hangs over humanity, no less cheerfully will Mohonk accept its share of the work of lifting that shadow.” As it happens, by the time the resort reopened in spring 1919, the worst of the disease had passed in the U.S. The crisis even worked to Mohonk's advantage: Americans valued fresh air and open spaces more than ever, and the resort promoted its classic pursuits of hiking, horse-riding and rowing on the lake.

The challenge after World War I turned out to be entirely different, says Mohonk's archivist, Nell Boucher. Guests loved the setting, but a national passion for "modernization" led them to expect new luxuries. "Mohonk was still operating with 19th century farm technology: ice was cut from the lake in winter for refrigeration, horse-drawn carriages used for transportation, the kitchen was wood-fired. The rooms had shared bathrooms and Franklin Stoves for heating," Boucher adds. The owner, Daniel Smiley, scrambled to keep up with Jazz Age expectations. "Renovations continued through the 1920s, which was expensive!" says Boucher. Mohonk continued to adapt: Ice stopped being cut from the lake in the 1960s, and the last shared bathrooms were gone in the 1990s. Today, Mohonk's Victorian splendor mixes with other 21st century niceties—most recently, a gourmet farm-to-table restaurant that bends an old Quaker principle of not serving alcohol. One pandemic innovation, using the boat dock as a stage for musical concerts in the lake's natural amphitheater, proved so popular that it is being kept up this summer, with jazz artists like Sweet Megg performing in a subtle nod to the 1920s. And for 2021, Boucher adds, "There's plenty of outdoor dining."

Gale Force Change: The Biltmore, Miami

The creator of the spectacular Biltmore, developer George Merrick, was not a superstitious man, so chose Friday March 13th for the groundbreaking ceremony in 1925. The future still looked rosy when the hotel opened its doors with a grand gala on January 15, 1926, attended by hundreds of socialites and journalists lured down from northeastern cities on trains marked "Miami Biltmore Specials," along with stars like Clark Gable and Esther Williams. The Gatsby-esque extravaganza saw guests quaffing champagne around what was then the largest hotel pool in the United States—lined with Greco-Roman sculptures—and dancing to three orchestras beneath the dramatically-lit Giralda tower, which was visible across the newly-designed neighborhood of Coral Gables, named after the coral rock used in landscaping. Seated at the overflow tables were 1,500 Miami locals.

Merrick's luck did not hold. Some eight months later, in September, one of the worst hurricanes in Miami's history—aptly known as "the Great Miami Hurricane"—swept in from the Bahamas, killing 373 in Florida. "The hotel became a refugee camp," says the Biltmore's historian, Candy Kakouris. "People squatted in the rooms, families crowded in and sleeping on the floor." The hotel never recovered, and the owner was bankrupted soon after. But a new owner defied the odds by reopening it in the depths of the Depression in 1931, creating a brief golden age: Guests included President Calvin Coolidge, baseball king Babe Ruth, Hollywood stars Douglas Fairbanks, Ginger Rogers and Judy Garland—and, perhaps most notoriously, the gangster Al Capone, who was shot at while staying in the 13th floor suite, which had been turned into a gambling den. Another mobster, Thomas "Fatty" Walsh was murdered in an unsolved gangland hit.

More benignly, Johnny Weissmuller (champion swimmer and the future Tarzan from the Tarzan film series of the 1930s and ‘40s) worked as a lifeguard in the grand pool. One day, he drunkenly streaked naked through the lobby, but when the hotel fired him, female guests petitioned to have him return.

For the ravishingly-decorated Biltmore, the real disaster came when the U.S. entered World War II at the end of 1941. The Federal government requisitioned the hotel as a military hospital, covering its marble floors with linoleum and painting its ornate walls a dismal battleship gray. In the 1950s, the hotel endured an even more Gothic existence under the Veterans Administration, with some rooms used as psych wards and morgues; there was a crematorium on the grounds and even a kennel for medical tests on dogs. Then, in 1968, the hotel was simply abandoned. Local teenagers would climb through its broken windows to explore the ghostly space and dare one another to spend the night on Halloween. Vagrants wandered the graffiti-covered halls and the once-grand pool was filled with tree limbs and snakes.

Various plans to demolish the gargantuan edifice fell through until the local Prescott family stepped in to purchase it. The Biltmore was restored and reopened in 1992—just before Hurricane Andrew hit. This time, the hotel survived, and even thrived. Over the last 30 years, Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama have both stayed in Al Capone's suite. A $35 million renovation completed in December 2019 seemed another example of unfortunate timing, with the pandemic lockdown coming soon after. But now the hotel is ready for 2021 with its landmark status burnished. "The building is a standing museum," boasts Tom Prescott, the current family business CEO, capitalizing on a recent interest in Florida history, as locals and outsiders have grown nostalgic for retro styles and antique glamour. His greatest pleasure, he says, is flying into Miami and hearing the pilot announce: "To the right is the world-famous Biltmore Hotel."

Star Power: Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel

Not every hotel could survive the Great Depression with the help of actor Errol Flynn making bathtub gin. But while many American hotels sank into economic ruin in the dark years after the 1929 Wall Street Crash, the Hollywood Roosevelt remained the glittering social epicenter of Los Angeles, thanks in large part to Flynn's bootleg activities conducted in the back room of the barber shop. The festive enterprise lured the actor's myriad celebrity friends, says the hotel historian, Juan Pineda, "The basement room where Flynn distilled his booze is now my office," he laughs.

Flynn's gatherings were in tune with the Roosevelt's ethos: it was built in 1927 with parties in mind. The hotel was financed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer head Louis B. Mayer, and the silent movie stars Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, so that Hollywood would have a space large enough for a decent movie premier gathering. Stars could stroll across the boulevard from Grauman's Chinese Theater or nearby El Capitan, into the soaring hotel lobby with palm trees and Moroccan flourishes, and gather in the ballroom, where, in fact, the first Academy Awards were held in 1929. (The World War I classic Wings took Best Picture; the entire ceremony, hosted by Fairbanks, lasted only 15 minutes).

Today, the sheer density of movie history in the Roosevelt is overwhelming. Shirley Temple practiced her dance steps on the stairs behind the lobby; Marilyn Monroe lived in a room above the pool for two years in 1949 and '50 as the then-little known Coppertone model named Norma Jean; and Clark Gable and Carol Lombard began their secret (and ultimately tragic) affair in the penthouse suite. It cost $5 a night then, today $3,500. ("Now even the crisps in the minibar will cost you $5," Pineda observes.)

But while the hotel had shrugged off the Depression—and World War II as a busy R-and-R venue—it could not defeat changing fashions. Hollywood sunk into decay in the 1960s and '70s, and developers began tearing down iconic buildings. Angelenos referred to the Roosevelt as "that old hotel," and the lobby was filled with travel agents and people waiting for nearby buses. "It felt like a Greyhound station," says Pineda. The ballroom where the first Oscars were held in 1929 had been painted over. ("They tried to hide the history," Pineda adds indignantly. "You can't do that to a hotel like this!")

In 1985, workers began demolishing the Roosevelt to build a parking garage—until they removed the lobby's false ceiling and discovered the beautifully ornate original from 1927. The building was declared a historic landmark, and new owners arrived to begin a renovation. Among other wonders, the original chandelier was discovered in 60 pieces in the basement and reconstructed. The artist David Hockney was brought in to create an "underwater mural" in the swimming pool, beneath 250 palm trees. The "luxury diner" was restored with its Venetian Murano glass chandeliers.

After the Roosevelt reopened in 1991, a new generation of stars including Paris Hilton and Lindsay Lohan put it back on the celebrity map. Around the pool are clothing pop-ups and the high-end tattoo parlor, Dr. Woo; a "secret" bowling alley and cocktail lounge has opened in the mezzanine; and a new restaurant, The Barish, opened in April to carry the hotel into the post-pandemic age. But its true allure is a new appreciation for Old Hollywood glamor. "Our cocktails are from the vintage 1927 recipes,” says Pineda.

Oil Dreams: La Colombe d'Or, Houston

In Houston, the oil crash of the 1980s was a cataclysm almost on par with an earthquake or city fire. "In 1986, the price of oil was sinking," recalls Steve Zimmerman, who had just opened a boutique hotel in the genteel Montrose district with only five art-filled rooms, each one named after a French Impressionist. "I said, 'If it goes down any more we'll have to eat the damn stuff!'" To survive, he came up with a creative idea: The hotel restaurant would offer a three course prix fix lunch for the price of a barrel of crude.

To promote the "Oil Barrel Special," Zimmerman put a real barrel of oil in the lobby with a computer on top where guests could check the day's price. "It got down to $9.08," he laughs now. "I was losing my fanny at lunch time! But it was worth it." The idea was a stroke of PR genius, provoking newspaper stories from New York to Tokyo and Berlin, and guaranteeing that the hotel would cruise through the crisis. It didn't hurt that one of the early fans was the news anchorman Walter Cronkite, who was charmed by the tiny hotel and its quirky history: the 1923 mansion was once owned by Francophile Texan billionaire and art collector Walter Fondren (founder of Humble Oil, the predecessor of ExxonMobil) who had gone on a buying spree to Europe and returned with rooms full of classic paintings, one of Marie Antoinette's bathrooms and a Parisian Metro station entrance, which sat in his backyard. But when it opened, the five-room La Colombe d'Or (named after an auberge in Provence beloved by Picasso) was a contrarian concept in a city happily knocking down its antique architecture in favor of gleaming glass towers. "In the 1980s, Houston hotels were going for big, bigger and biggest," Zimmerman says. "Montrose was cheap, and had a more human-sized feel. I thought: 'I'm going to make the littlest hotel in Houston. Nobody can out-little us!'" The success of the Oil Barrel Special and the hotel's alluring decor, with lush wallpaper, over 400 artworks, fine sculptures in the garden and assorted "Gallic bric a brac," meant that the hotel became the Houston address for visiting celebrities, from Peter Jennings to Bishop Tutu and Madonna.

Zimmerman's PR master stroke has had a long afterlife. In 2015, when oil prices fell radically to about $45 a barrel, Zimmerman revived the idea for a three-course dinner—although Houston's economy had diversified by then, and was no longer reliant on black gold. More recently, La Colombe d'Or hardly missed a beat in the pandemic. The hotel had already closed for renovations and it reopened in March with two lavish new additions: a set of secluded New Orleans-style bungalows, and a modern 34-story residential tower with 18 guest suites and an exterior emblazoned with a 45-foot-high mural by French street artist Blek Le Rat. In Houston, oil and art are forever intertwined.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/7d/c17d6907-5f24-4f66-9827-462ef87fc889/mohonk_mountain_house_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/49/a4/49a4a49c-da0a-48d2-b0ea-51ab81cb814c/mohonk_mountain_house_banner.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)