Five Places to See Trilobites in the United States

In a new book, fossil collector Andy Secher takes readers on a worldwide trek of trilobite hotspots

:focal(1454x969:1455x970)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/24/db/24dbd0be-b7c1-4255-8d75-189e1fcd9f5a/gettyimages-523645056.jpg)

Andy Secher remembers the first time he came face to face with a fossil. He was seven years old and riding the school bus when the bus driver showed him and the other students a specimen that he had unearthed during a weekend dig in Upstate New York.

“I was fascinated,” Secher says. “And after that, I was kind of hooked.”

Hooked is an understatement. Fast forward to adulthood and Secher has amassed a personal collection of some 5,000 fossils, which he houses inside his 1,650-square-foot Manhattan apartment. His passion for fossils, and specifically trilobites—extinct hard-shelled marine invertebrates that existed during the Paleozoic Era, a time period that stretched around 289 million years—led him to a career as a field associate in paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). There, for the past 15 years, he has been co-editor of the museum’s popular Trilobite website.

“I often joke that I have the largest trilobite collection on the Upper West Side,” Secher says. (The fact that the world-renowned museum, with its thousands of specimens, is less than a half-mile walk from his apartment makes the quip all the more humorous.)

So, what is it about trilobites that make them different from other fossils? For Secher, the answer is simple. In his book he writes, “Even at a very early stage in the history of life on our planet, the trilobite design had already proven to possess a certain degree of evolutionary perfection.” Add to that the fact that there’s such a variety of specimens out there, resembling everything from what he describes as a “hydrodynamic spaceship” to “nothing more than a primordial meatloaf,” and it’s easy to see why collectors like Secher are thirsty for trilobites.

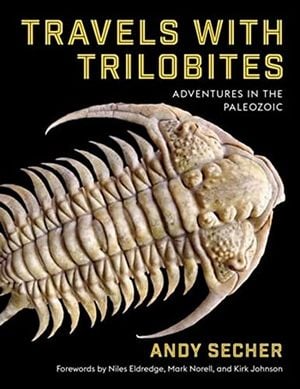

More recently, Secher added another bullet point to his résumé with the release of his book Travels with Trilobites: Adventures in the Paleozoic, which takes readers on a journey to some of the best places around the world to see these ancient arthropods, from museum collections to quarry fossil beds.

Travels with Trilobites: Adventures in the Paleozoic

Andy Secher invites readers to come along in search of the fossilized remains of these ancient arthropods. He explores breathtaking paleontological hot spots around the world―including Alnif, Morocco, on the edge of the Sahara Desert; the Sakha Republic, deep in the Siberian wilderness; and Kangaroo Island, off the coast of South Australia―and offers a behind-the-scenes look at museums, fossil shows, and life on the collectors’ circuit.

“I geared my book for the layman and not for experts,” Secher says. “When writing it, I looked to [the late chef and documentarian] Anthony Bourdain, who centered his own writings not just on food, but on the places he visited and the people he met. I took the same approach here.”

Which makes sense, considering that Secher started off his trilobite trek as a layman himself. For 30 years, he was the editor of the rock ‘n’ roll music magazine Hit Parader, while he honed his expertise in trilobites.

“My previous career allowed me to travel the world and visit museums, go to dig sites, and often write about trilobites for different science publications,” he says. “I began writing about them as an enthusiast, simply out of love and knowledge.”

Trilobites, or “bugs” as they’re often called within the paleontology community—they look eerily similar to insects and contain three main body segments as well, including the cephalon (head), thorax (body), and pygidium (tail)—are actually quite common as far as fossils go. With some 20,000 scientifically recognized trilobite species, they can be found all over the world. However, their presence is more abundant in some spots than others.

Anticosti Island, for example, is a remote landmass off the southeastern coast of Quebec, Canada, and a “trilobite treasure trove,” according to Secher, due to its thick sedimentary layers that reveal North America’s most complete geological strata stretching from the Silurian period (approximately 444 million to 419 million years ago) to the Ordovician period (approximately 485 million to 444 million years ago). Over the years, 52 trilobite species have been discovered on the island, including well-preserved Dicalymene schucherti, Failleana magnifica and Arctinurus anticostiensis specimens. Interestingly, trilobites found on Anticosti are known for being two to three times larger in size than similar ones found elsewhere around the world.

Secher also points to the limestone rich Fillmore Formation in western Utah, which he describes as “America’s trilobite paradise” thanks to its storied history as a place to see trilobites outside the walls of a museum. The state’s native Ute tribe, in the 19th century and probably earlier, would drill holes into what they described as “animals of stone” and wear their creations around their necks for good luck.

“To further magnify the perceived protective powers of these impressive invertebrates, Native American petroglyphs depicting what clearly appear to be trilobites have been found adorning ancient cliff faces throughout the region,” Secher writes in his book. “The Ute may have been the first to recognize the state’s trilobite fauna as something extraordinary, but they certainly weren’t the last.”

So, what is it about trilobites that have made them collectibles for such a long period of time? For starters, part of the allure is that most trilobites “can be held in the palm of your hand,” Secher says.

“A complete trilobite specimen can be embedded into a single piece of limestone shale,” he says. “You definitely can’t say that about a dinosaur skeleton.”

Feast your eyes on trilobites at these five spots in the U.S.:

American Museum of Natural History (New York City)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/fa/69fadf0c-8f92-4e57-8401-dca5939c17dc/14759235339_243dbb41b5_k.jpg)

While the towering 122-foot-tall Titanosaur may be the museum’s biggest draw, its extensive collection of trilobites is also worth seeing, especially for its sheer breadth of specimens that come in a variety of shapes and sizes spanning the Paleozoic Era. Secher helped obtain the Levi-Setti collection several years ago that contains some 500 specimens collected by the late physicist and trilobite collector Riccardo Levi-Setti.

U-Dig Fossils (Delta, Utah)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/47/b3/47b35bfb-82be-4b1d-9616-623b40baa2d6/33304769586_67eaf34794_o.jpg)

Located in west-central Utah, this family-run facility offers visitors access to 40 acres of excavated shale to search for trilobites that date back millions of years to the mid-Cambrian period. In 1994, the facility began as part of a college project by the owner, Shayne Crapo, whose uncle happened to be leasing the land, and it has been attracting fossil hounds ever since. Rates for adults begin at $33 for a two-hour dig. During a four-hour dig, most visitors can expect to find anywhere from ten to 20 trilobites ranging in length from 1/8th of an inch to 2 inches. Some of the most commonly found species include Elrathia kingi, Asaphiscus wheeleri and Peronopsis interstricta.

National Museum of Natural History (Washington, D.C.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/83/33/833367ef-d31c-4d4d-8838-52dbc9c940c6/nmnh-hall_of_fossils.jpeg)

The museum’s permanent David H. Koch Hall of Fossils is renowned for many reasons, one being that it contains some of the rarest known trilobite specimens in the world. These include a Bathynotus holopygus from Vermont and a Trimerus vanuxemi from West Virginia. However, it’s the world’s only known complete Apianurus sp. specimen from New York’s Walcott/Rust quarry that has become the collection’s showpiece.

Penn Dixie Fossil Park and Nature Reserve (Blasdell, New York)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/62/ea/62ea1f11-4bed-4da9-b077-ea87b799d15d/penn_dixie_fossil_park.jpg)

Located on a former cement quarry near Buffalo, this 54-acre spot became a park and nature reserve in mid-1990s when the Hamburg Natural History Society acquired the land. Fossils found at the site date back approximately 380 million years to the Devonian Period and include trilobites in addition to shelled brachiopods and crinoids, a class of marine animals that include starfish and sea urchins. Penn Dixie features open-pit digging, but also offers a private collecting expedition where a trained guide takes groups of two to eight people to dig sites normally off limits to the general public. Penn Dixie claims that “everyone will find something,” and its website includes a gallery of previous treasures.

Tucson Gem and Mineral Show (Tucson, Arizona)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/d8/cd/d8cd09cc-5c44-4705-bb30-f95ff8a67c01/tucson_gem_and_mineral_show_tm.jpeg)

Everyone from serious collectors to fossil newcomers flock to this annual four-day event in southern Arizona. Advertised as the “largest, oldest, and most prestigious gem and mineral show in the world,” Secher describes it in his book as somewhere where you can “come face to cephalon [head of a trilobite] with a choice selection of spectacular trilobite specimens, each designed to test the bounds of both your knowledge and your bank account.” Over the years, he’s added many specimens to his collection from the show, including a large lichid from the Middle Ordovician of Russia. While this year’s event has already come and gone, next year’s is scheduled for February 9-12, 2023.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.