The Deadly Lake Where 75 Percent of the World’s Lesser Flamingos Are Born

Lake Natron will kill a human, but flamingos breed on its salty water

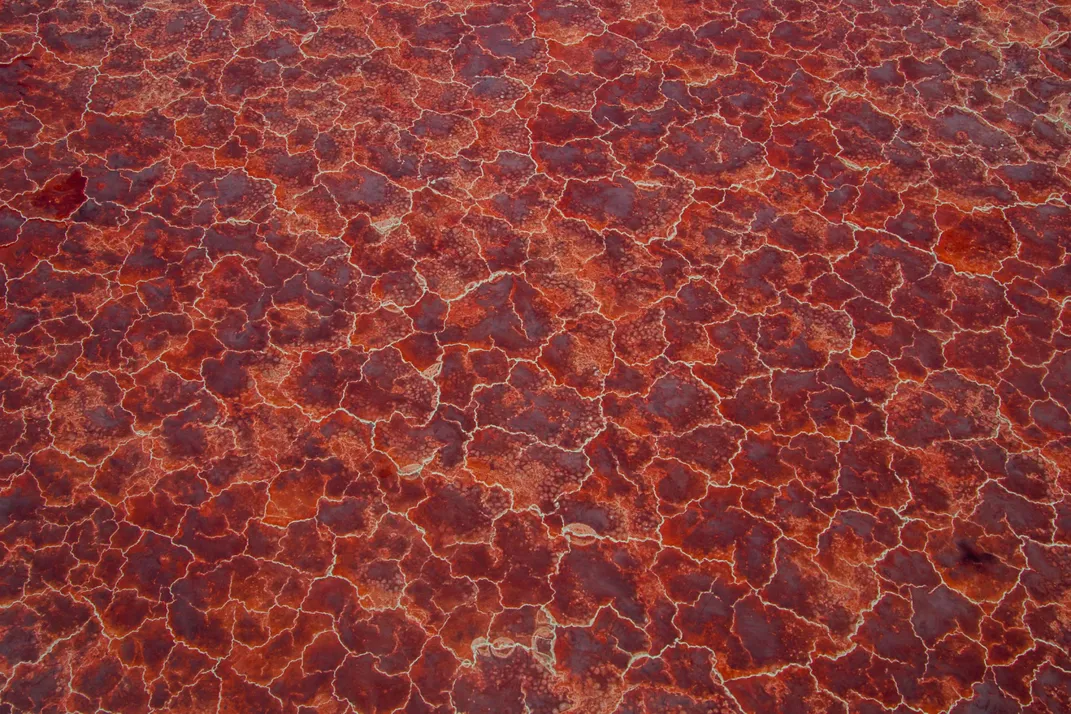

At the base of a mountain in Tanzania’s Gregory Rift, Lake Natron burns bright red, surrounded by the calcified remains of animals that were unfortunate enough to fall into the salty water. Bats, swallows and more are chemically preserved in the pose in which they perished; deposits of sodium carbonate in the water (a chemical once used in Egyptian mummification) seal the creatures in their watery tomb. The lake's landscape is surreal and deadly—and made even more bizarre by the fact that it's the place where nearly 75 percent of the world's lesser flamingos are born.

The water is oversaturated with salt, can reach temperatures of 140 degrees and has a pH between 9 and 10.5—so corrosive that it can calcify those remains, strip ink off printed materials and burn the skin and eyes of unadapted animals. The unique color comes from cyanobacteria that photosynthesize into bright red and orange hues as the water evaporates and salinity rises; before that process occurs during the dry season, the lake is blue.

But one species actually makes life among all that death—flamingos. Once every three or four years, when conditions are right, the lake is covered with the pink birds as they stop flight to breed. Three-quarters of the world’s lesser flamingos fly over from other saline lakes in the Rift Valley and nest on salt crystal islands that appear when the water is at a very specific level—too high and the birds can’t build their nests, too low and predators can waltz across the lake bed and attack. When the water hits the right level, the baby birds are kept safe from predators by a caustic moat.

“Flamingos have evolved very leathery skin on their legs so they can tolerate the salt water," David Harper, a limnology professor at the University of Leicester, tells Smithsonian.com. "Humans cannot, and would die if their legs were exposed for any length of time.” So far this year, water levels have been too high for the flamingos to nest.

Some fish, too, have had limited success vacationing at the lake—lower salinity lagoons form on the outer edges from hot springs flowing into Lake Natron. Three species of tilapia thrive there part-time. “Fish have a refuge in the streams and can expand into the lagoons at times when the lake is low and the lagoons are separate,” Harper said. “All the lagoons join when the lake is high and fish must retreat to their stream refuges or die.” Otherwise, no fish are able to survive in the naturally toxic lake.

This unique ecosystem may soon be under pressure. The Tanzanian government has reinstated plans to begin mining the lake for soda ash, used for making chemicals, glass and detergents. Although the planned operation will be located more than 40 miles away, drawing the soda ash in through pipelines, conservationists worry it could still upset the natural water cycle and breeding grounds. For now though, life prevails—even in a lake that kills almost everything it touches.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)