On the islet of Useppa, I was sleeping with the CIA. Not as part of any covert operation, needless to say; it just came with the décor.

I had taken the master bedroom at the Collier Inn, a mansion and fishing lodge that rises in whitewashed glory above the mangroves of Florida’s Gulf Coast, and plunged straight into a Cold War conspiracy. In one of the most peculiar twists in the history of American tourism, undercover CIA agents took over this former millionaire’s abode in the spring of 1960, when Useppa Island, then a down-at-the-heels holiday resort, transformed into a secret training camp for the invasion of Fidel Castro’s Cuba that would become known as the Bay of Pigs.

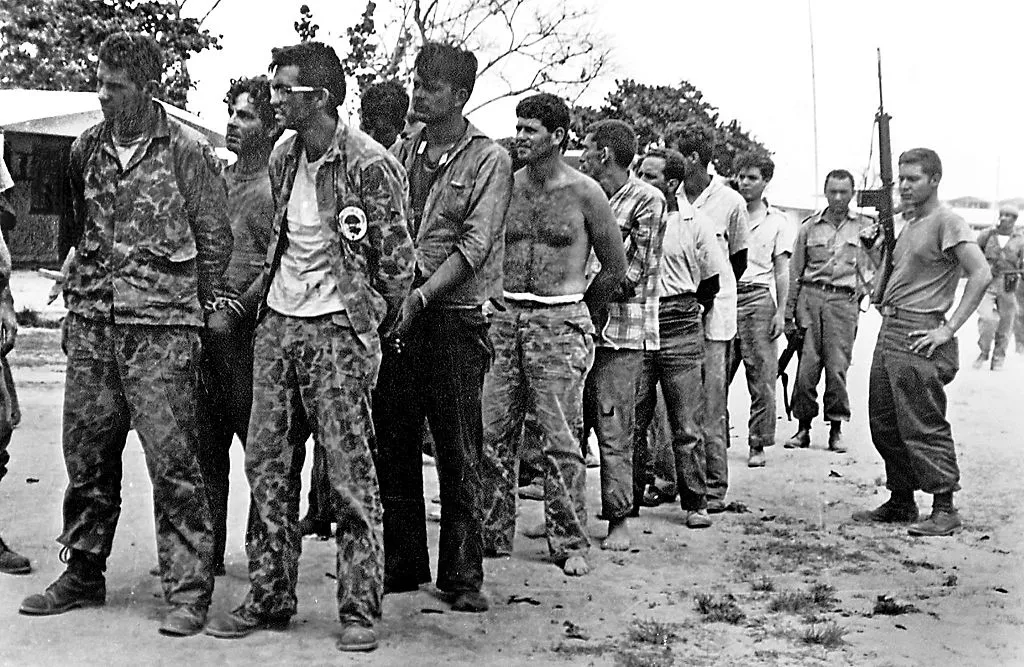

The amphibious assault on Cuba’s southern coast, which started 60 years ago on April 17, 1961, as an attempt to depose the leftist revolutionary, was a fiasco, one of the greatest humiliations for the United States. After three days of fighting, the surviving 1,200 or so CIA-trained troops surrendered to the Castro government, who put the invaders on public trial in Havana, then sent them to prison.

But that defeat must have seemed far away when the agency first chose Useppa.

The island has always had an otherworldly serenity. At dusk, I strolled from my four-poster bed in the Collier Inn to a balcony, framed by Grecian columns, that looked out through swaying palm trees to sparkling blue waters. Across the horizon, a rash of verdant mangrove islands glowed in the sunset. If nothing else, America’s Cold War spooks had excellent taste.

From this regal viewpoint, it was easy to imagine Useppa’s attraction as a base for furtive intrigue. In 1960, this entire stretch of the southern Gulf Coast was a tropical maze with a spirit closer to the wild, mythical era of pirates, smugglers and bootleggers than the tourist-friendly Sunshine State of modern times. Today, Useppa is hardly inaccessible, but it has remained largely undeveloped and a private island resort. It was purchased in 1993 by a Floridian magnate and its structures restored to their antique, Jazz Age grandeur; the Collier Inn has a particular Old World charm, decorated with mounted tarpon fish and antique photographs, including one of Teddy Roosevelt weighing his catch on the island’s jetty, evoking the fairytale vacations of America's leisured elite in ages past.

And while the island’s dramatic connection to the Bay of Pigs invasion is all but unknown to the outside world, it is a beloved part of local lore. A small museum run by a local historian highlights the saga, and veterans have returned for reunions over the years. “Useppa was a paradise,” sighed one, Mirto Collazo, when I found him later in Miami. “It was like a vacation.”

Particularly, he might have added, compared to what followed at the Bay of Pigs, whose very name has a “phantasmagorical” tinge, writes historian Jim Rasenberger in The Brilliant Disaster, “evoking bobbing swine in a blood-red sea.”

* * *

When I had first read about Useppa’s Cold War cameo, the details were obscure; I could only find a few stray references in specialist history books. The only way to unravel its mysteries, I realized, was to make the pilgrimage to the idyllic island itself. Soon I was flying into Tampa and driving a rental car south, emboldened by two vaccine shots safely in my arm but still packing an array of masks for social encounters. No sooner had I turned off the busy I-75 freeway than I entered Old Florida, following routes with names like Burnt Store Road to the hamlet of Bookelia on Pineland (a.k.a. Pine Island). There, the Useppa Island Club’s private ferry took me across dark, glassy waters as pelicans swept low and dolphins arched past. With each twist of the 20-minute ride, the decades fell away, and as I scrambled onto Useppa’s pier, a manatee slid lazily below. It was clear that Useppa had lost none of its retro atmosphere. No cars are allowed on the island, and the few residents —mostly elderly and deeply tanned—either power-walk or jog past, or trundle by on electric golf carts, always giving a friendly wave.

“This is where it all began!” said Rona Stage, the director of the museum as we strolled the “pink path,” a rose-hued trail that runs the length of the island shaded by lush flowers, palm trees and an ancient banyan. Like any good spy on a mission, my first step was to get the lay of the land—not a difficult project on Useppa, which is only a mile long and never more than a third of a mile wide. In fact, Stage’s guided CIA tour covered perhaps 300 yards.

The first highlight was the four now-privately-owned wooden bungalows where the 66 recruits, young Cuban exiles who were mostly in their 20s but with a few in their teens, were lodged. They had been built from heart pine so they wouldn’t rot, Stage said, and were once brightly painted; while three are now gleaming white, one had been restored by its owner to its original lemon tint. The Collier Inn, where the CIA agents took up residence and where I was to spend the night, also had its dining room converted into the mess hall for the trainees. Today’s pro shop building near the swimming pool and croquet court was where the agents and doctors conducted an array of tests on the men, including lie detector and Rorschach inkblot tests to ascertain their psychological stability and political reliability, intelligence assessments and extensive physical examinations.

We circled back to the charming museum, where a corner focuses on the Bay of Pigs expedition, including a replica camouflage uniform and some dramatic photos of the battle. It was sobering to see a plaque presented by the Useppa veterans with the names of the men who had trained here, including coded markers showing who had been killed in combat, executed by firing squad, killed in training or imprisoned in Havana.

The museum also revealed Useppa’s surprisingly rich backstory. It turns out that the CIA had chosen it for the same reason that had lured travelers for generations: the chance to fall off the map. Beloved by tarpon fishermen since the 1870s, Useppa’s golden age began in 1911, when the island was purchased for $100,000 by a high-living Floridian millionaire named Barron Collier, so he and his friends could relax—and party—far from prying eyes.

By the Roaring Twenties, Collier had built cottages, the golf course, his mansion and a lavish hotel where Prohibition could be ignored. The Gatsbyesque magnate reputedly filled the rooms with showgirls while his wife and children slept in distant bungalows, and celebrity guests arrived from every walk of American life. According to (possibly exaggerated) legend, they included Vanderbilts, Rockefellers and Roosevelts; Thomas Edison and Henry Ford; and the boxer Jack Dempsey, who partied with employees on a speck of land nearby dubbed Whoopee Island after the hit song “Making Whoopie.” Old Hollywood stars Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy chose the private island for trysts, as did, rumor holds, Shirley Temple.

Collier died in 1939, and Useppa fell into decay. During World War II, the larger hotel was battered by hurricanes and finally burned down, but the family maintained Collier's personal plantation-style mansion, today's Collier Inn, as a fishing lodge. By 1960, this aura of genteel tropical dereliction evidently made the island the perfect base for the CIA to gestate its wildly ambitious plan to violently overthrow the Castro government, which President Eisenhower had authorized and his successor, John F. Kennedy, would uneasily inherit. In May 1960, a Miami businessman named Manuel Goudie y de Monteverde leased the island for the CIA, and recruits arrived soon after to form what would be called Brigade 2506.

Combining the references I had unearthed and Stage’s stories, I pieced together makeshift proceedings. The young Cubans had been recruited from the growing anti-Castro exile community in Miami—the CIA’s name was never mentioned—and they were summoned after dark in groups of eight to ten in the carpark of the White Castle diner downtown. Without being told their destination, they were driven in a van with the windows blacked out for three hours across the Everglades to a fishing shack and then piled into a speedboat. Three armed Americans met them on the dark island dock and showed them their quarters.

For the next two months in this unlikely boot camp, the CIA agents went through the barrage of tests and trained the recruits in cryptology, radio operation, outdoor survival and demolition techniques. They also provided them with weapons—leftover World War II-era rifles and Thompson machine guns for practice in the mangroves near the overgrown golf course. The agents insisted the guns had been donated by a wealthy Cuban benefactor—certainly not the U.S. government. Nobody was fooled, and the young men joked that they were working with a new “CIA,” the “Cuban Invasion Authority.”

Even in Useppa, total secrecy was hard to maintain. The police sheriff for the area had been told by the CIA to turn a blind eye to the nocturnal comings and goings on the island, but rumors did spread in the tight-knit fishing communities nearby. “The locals definitely knew something was going on,” Stage said. “They knew all these groceries were coming in from [nearby] Punta Gorda.” According to another story, a yacht full of drunken revelers in swim shorts and bikinis tried to land on the pier but were turned away by machine gun-toting camouflaged guards, igniting further speculation.

* * *

Of all the history in the Useppa museum, the most exciting to me was correspondence between veterans who had attended reunions there, almost all of whom lived in Miami. It is the twilight of the Cold Warriors—the majority are in their 80s, the youngest is 77—and so while in southern Florida, I traveled to "the so-called Capital of Latin America" to hear their eyewitness accounts myself before they are lost forever.

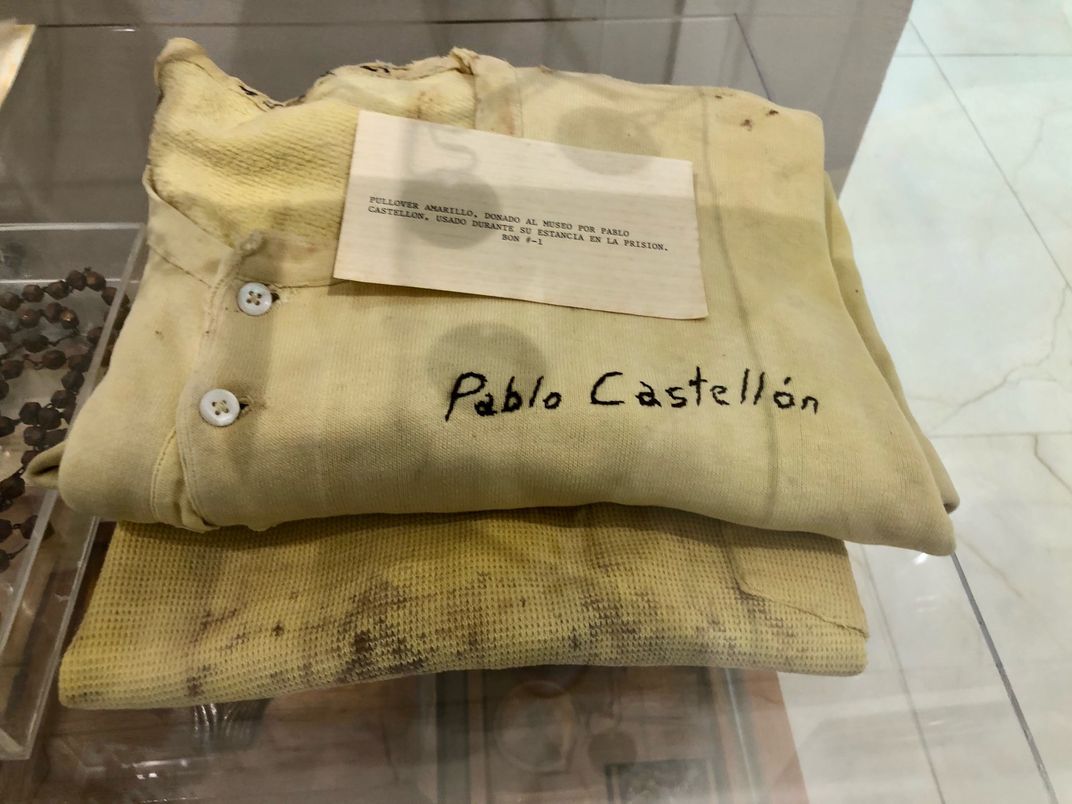

I dropped by the veterans’ traditional social hub, the Bay of Pigs Museum and Library of Brigade 2506, which has operated since the 1980s in a pleasant house on Calle 9 in Miami’s Little Havana. Then I took a taxi to the new Hialeah Gardens Museum Honoring Assault Brigade 2506, a bright, purpose-built structure in a quiet residential Cuban community, with a vintage tank and B-26 fighter bomber sitting on the grounds. Both museums are filled with relics from the invasion, including an array of weapons, uniforms and personal items brought back from their time in prison, such as toothbrushes and drawings done in the cells.

The Bay of Pigs story had always seemed abstract to me, but it took on a new reality as the veterans relived it. The amphibious assault began before dawn on April 17 and went awry from the start, as the landing craft hit coral and the 1,300 or so men were forced to wade 75 yards through the waves. The CIA’s grand plan turned out to be wildly misconceived. It was hoped that after the “Liberation Army" secured a foothold, a provisional government would be flown in and the Cuban population would rise up in rebellion against Castro.

But most Cubans in 1960 still strongly supported Fidel and the revolution, and any slim chance of success was undermined by U.S. equivocation as the invasion unfolded. Fearing a military reaction of the Soviets, JFK refused to have Americans openly implicated by using U.S. airplanes or navy destroyers: he limited promised air strikes on the first day of the attack and canceled them entirely on the third. The tiny Cuban air force was able to strafe and harass the landing craft and the CIA-trained force on the beaches as Castro’s militia descended on them on land; promised reinforcements and supplies simply did not materialize. By the end of April 20, most of the 1,200 survivors had thrown down their arms; the rest were soon rounded up in the nearby Zapata swamp. Some 114 men on the CIA side had been killed, and (officially) around 175 Cubans died, although the numbers may be higher.

The surviving "mercenaries" (as Cubans called them derisively) were tried in Havana and sentenced to 30 years in prison. Almost all Brigade 2506 prisoners were released to the U.S. after 20 months in exchange for cash, food and medical supplies, and in December 1962, were greeted as heroes by the President and Jackie at the Orange Bowl in Miami.

To find out more about Useppa, I was invited to return to the Hialeah museum during a Sunday memorial for one of their recently deceased compañeros, fighter pilot Esteban Bovo. As their families chatted, several veterans who had trained on its shores reminisced about that spring in 1960. Vicente Blanco-Capote, was only 17 when he had been ferried to the island after dark with eight others. “I didn’t know where I was,” he said. “A big tall blonde American guy met us on the dock.” This turned out to be one of three CIA instructors the recruits knew simply as “Bob,” “Nick” and “Bill.” Another garrulous veteran, 82-year-old former Cuban Army soldier Mirto Collazo, said he had been suspicious that the mysterious transfer from Miami was a trap. “A friend gave me a pistol. He said, ‘Hide it, because you don’t know what is going to happen!’ Of course, they took it from me when I arrived.”

But once the young recruits had settled into the quarters, they realized Useppa was no Devil’s Island, the notorious French penal colony. “It was luxury!” Blanco-Capote marveled. “An island of millionaires! There was no air conditioning in the bungalows, but they had hot and cold running water.” And the next morning, the fresh-faced recruits could hardly believe their luck as they explored the eerie setting, surrounded by lush greenery and turquoise waters. The trio of CIA agents were nothing if not accommodating, Blanco-Capote added. “‘Can we get you anything?’ they asked. ‘You want a pipe?” They got me one and also one for everyone else. And any food you wanted! So long as it was American-style—and, of course, no rum.” Days went by like summer camp, as the young Cubans swam, and played soccer and beach volleyball. They lifted old wooden railway sleepers for weight training. At night, they played cards and watched TV.

On July 4, 1960, the holiday ended, and the CIA shipped the 66 Cubans off to two other secret training camps in the mosquito-filled jungles of Panama and mountains of rural Guatemala—both with far harsher conditions, rusting lodging, bad food and grueling physical training regimes. There, they were joined by other recruits, who eventually numbered 1,500 and took the name Brigade 2506 (after the code number of a popular member from the original Useppa troupe, Carlos Rodríguez Santana, who died accidentally when he fell off a cliff in Guatemala). But the trials in Central America paled in comparison to the situations the men would soon face in Cuba, as I realized when one Useppa alumnus, 85-year-old Jorge Guitíerrez Izaguirre, nicknamed "El Sheriff," opened his shirt to reveal a wound in the middle of his chest, the exit hole from a bullet. He said that he was caught in a shootout during the covert operation.

History rightly remembers the Bay of Pigs as a resounding failure. Not only was it a massive embarrassment for the U.S. as undeniable evidence of CIA involvement piled up, it achieved the precise opposite of its aim. Castro’s right-hand man Che Guevara cheekily thanked JFK for the attack through an intermediary: “Before the invasion, the revolution was shaky. Now, it is stronger than ever.” Cuba was pushed towards its unique brand of tropical communism—and the waiting arms of the U.S.S.R.

* * *

For the 50th anniversary of the invasion in 2011, a reunion brought some 20 veterans to Useppa Island with their families. Standing in a group outside the museum, "El Sheriff" Jorge Guitíerrez had recited a poem written by one of their leaders about the young Useppa recruit who died while training in Guatemala, the first casualty of the invasion. “It was very moving,” Stage recalled.

For the 60th anniversary this year, under the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic, the dwindling membership of Brigade 2506 decided against scheduling a reunion. It is unclear whether there will be another. But hopefully the memory of this peculiar Cold War episode will live on in the small island, perplexing and bemusing guests to this lovely outpost in the mangroves for generations to come.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bd/18/bd1834b5-d8a6-4720-803d-28c1a7aabad4/useppa_island_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/0e/400ef8a3-5592-4dd8-a3ae-c0bf5a44d112/useppa_island_banner.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tony.png)