Follow Ernest Hemingway’s Footsteps Through Havana

Sixty-five years after nabbing a Nobel, many of Papa Hemingway’s favorite haunts are still open to the public

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/13/a113cd1c-4eca-4330-99c7-c94bba8a1b3a/1024px-bodeguita_del_medio-hemingway_havana_cuba.jpg)

When Ernest Hemingway penned his novel The Old Man and the Sea at his farm outside Havana, he likely had no idea the success it would receive, garnering him both a Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1953 and a Nobel Prize in literature in 1954.

When it was announced, 65 years ago on October 28, that he had won the Nobel, Hemingway thought other writers were better suited to the award. "As a Nobel Prize winner I cannot but regret that the award was never given to Mark Twain, nor to Henry James, speaking only of my own countrymen," he told the New York Times, just two hours after the official word from Stockholm. "Greater writers than these also did not receive the prize. I would have been happy—happier—today if the prize had gone to that beautiful writer Isak Dinesen, or to Bernard Berenson, who has devoted a lifetime to the most lucid and best writing on painting that has been produced, and I would have been most happy to know that the prize had been awarded to Carl Sandburg. Since I am not in a position to—no—since I respect and honor the decision of the Swedish Academy, I should not make any such observation. Anyone receiving an honor must receive it in humility."

The Old Man and the Sea tells the story of a Cuban fisherman (supposedly inspired by a fisherman friend, Gregorio Fuentes, of Hemingway's and his own fishing trips) who caught a giant fish‚ only to have sharks eat the fish, leaving him with just a skeleton to bring home. Because he had such a connection with Cubans and the spirit of the country, Hemingway was considered a Cubano Sato, or garden variety Cuban, by residents. He became a regular at local establishments and even started a youth baseball team. Those close to him just called him Papa.

The writer first found his way to Cuba with his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, in April 1928. It was a simple layover in Havana en route from Paris to Key West, but the city captured his attention enough for him to return to the country multiple times and eventually purchase his own residence there in 1940 (this time with his third wife, Martha Gellhorn). His farm was built by Spanish architect Miguel Pascual y Baguer in 1886 and sits about 15 miles outside Havana, with a guesthouse and a view to downtown.

"I live in Cuba because I love Cuba—that does not mean a dislike for anyplace else," Hemingway once told Robert Manning at The Atlantic. "And because here I get privacy when I write."

Hemingway loved Cuba so much that he dedicated his Nobel Prize to the country, noting (according to the Independent) that “This is a prize that belongs in Cuba, because my work was conceived and created in Cuba, with my people of Cojimar where I’m a citizen.”

In 1960, about a year before his death, Hemingway left Cuba for good. But fans of the novelist today can still visit a handful of his favorite spots.

Finca Vigía

Hemingway and his third wife, Martha, bought this 1886 house in 1940, after Martha discovered it in local ads the year before. The author lived here for 20 years, penning The Old Man and the Sea and finishing For Whom the Bell Tolls, among other works, from within its walls. He and his fourth wife, Mary Welsh (who moved in after Ernest and Martha divorced in 1945) abandoned the house in 1960, following Castro’s rise to power. The house is now owned by the Cuban government and operated as a museum. Everything has been meticulously preserved as it was when Hemingway left—bottles still sit on a serving tray, thousands of books still line the shelves and magazines are still spread out on the bed. It's all authentic to the day the author and his wife left. His fishing boat, Pilar, is preserved at the house as well, tucked inside a shelter on the property. It's likely that Hemingway's old fishing pal, Gregorio Fuentes, inspired the main character in The Old Man and the Sea—though Hemingway never said for sure. For preservation purposes, visitors are not actually allowed to enter the house but are invited to peer in through the doors and windows, which are always open (unless it’s raining).

Hotel Ambos Mundos

Before moving into Finca Vigía, Hemingway lived mostly at the Hotel Ambos Mundos in Old Havana, a salmon-colored building with 52 rooms. Hemingway stayed on the 5th floor, in room 511, which has now been transformed into a permanent museum dedicated to the author’s time there. While he lived in the hotel from 1932 until 1939, he began working on For Whom the Bell Tolls. He preferred room 511 specifically because he could see both Old Havana and the harbor, from where he often took his boat out fishing. In the lobby, guests will find framed photos of the author, and in his former room, several of his belongings—including a typewriter, glasses and a writing desk. Although room 511 is a museum now, guests can still rent rooms on the same floor to share the view Hemingway loved. (Or at least part of it; the author's room was on a corner.)

Floridita Bar

Hemingway can still be seen leaning one elbow at the bar in the Floridita, a restaurant and pub he frequented—though, this Hemingway is a life-size bronze statue. The author frequently walked the ten minutes from Hotel Ambos Mundos to Floridita, so he could enjoy a drink—often his beloved daiquiri—made by the "Cocktail King of Cuba," bartender Constantino Ribalaigua Vert. Constante (as the locals called him) died in 1952, but not before making a certain daiquiri famous at the Floridita: the Papa Doble, or the Hemingway Daiquiri, made with less sugar and more rum as Hemingway preferred it.

La Bodeguita del Medio

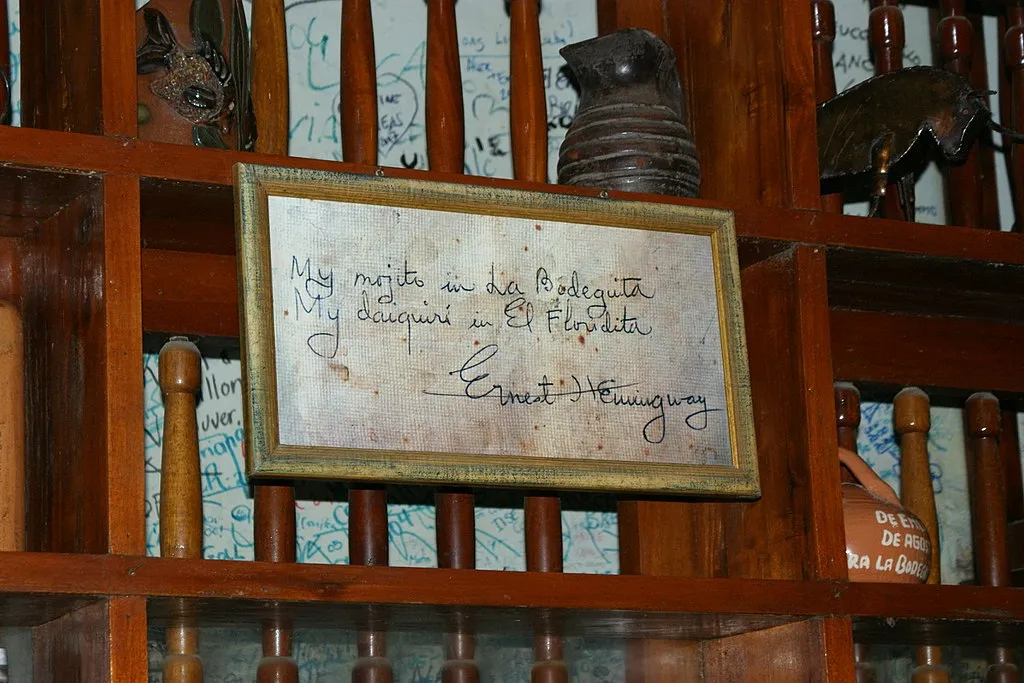

Rumored to be the birthplace of the mojito, La Bodeguita actually began its life as a small grocery store and corner shop. In 1942, the new owner started serving meals to friends and family, and by 1949, had turned the shop into a restaurant. Celebrities galore have come to La Bodeguita—Hemingway, Nat King Cole and Brigitte Bardot—and even Fidel Castro. Nearly all have signed the walls, which are covered in a cacophony of greetings and scrawls paying tribute to the bar. Hemingway supposedly left his own mark on one of the walls there as well; a framed reproduction (or an authentic signature, or a complete forgery, depending on who you ask) of his scribble proclaims “My mojito in La Bodeguita, my daiquiri in El Floridita” from its place hanging behind the bar.

Tropicana

This open-air cabaret has drawn the high-class jet-setting crowd for nearly 80 years, hitting its high point in the 1950s when guests included notables like Hemingway, Marlon Brando and John F. Kennedy. To this day, every show is stuffed full of showgirls in feathers and sequins, dancing and singing. It's an all-out party in the crowd, as people take to the aisles to dance alongside other revelers. Guests can toast to Hemingway’s legacy as a frequent visitor to the shows at the Tropicana; included in the ticket price is a cigar for the men, a flower for the women, and a bottle of rum for four people to share.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)