Following Beethoven’s Footsteps Through Vienna

For the composer’s 250th birthday, visit the apartments where he lived, the theaters where he worked and his final resting place

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/d0/13d09742-b2f8-42e6-8389-a9a510c05da9/beethoven_statue_bonn.jpg)

Composer Ludwig van Beethoven moved to Vienna twice. The first time, in 1787, he was only 17 years old and meant to study under Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s tutelage. But as soon as he’d arrived, he got word his mother was near death. He traveled back to Bonn, Germany, his hometown, to stay by her side. Beethoven ended up staying in Bonn for five years, and while he was there, Mozart became ill and died in December 1791. This time intent on studying under Franz Joseph Haydn, Beethoven moved back to Vienna in 1792.

Vienna is where Beethoven remained for 35 years, through his worsening and ultimately total deafness, composing the entire time. The composer moved more than 60 times while he lived there, and performed throughout the city at various theaters and halls—and sometimes in palaces. He died in 1827, when he was 56, from liver cirrhosis.

In 2020, the world will celebrate Beethoven’s 250th birthday. More than 1,000 performances are planned throughout Germany, incuding in both Bonn (his birthplace) and Vienna, to mark the occasion. Expect to hear his works from the London Symphony Orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra, and more. Take in one of the many concerts, perhaps, but also consider honoring Beethoven's legacy with this guided tour to sites in Vienna tied to the composer's life.

Beethoven Museum, Probusgasse 6

With Beethoven’s hearing continuing to get worse, he moved in 1802 to a small apartment with a courtyard at Probusgasse 6 with the intent to try and heal his ears. The area, Heiligenstadt, was known for mineral-rich baths thought to have restorative powers. Plus, his doctor recommended he move to the quieter village to give his ears a rest. In 1802, though, he learned the increasing deafness was not going to get any better and fell into a deep depression. From his apartment, he wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament. It was a letter to his brothers, where he spoke of his condition and the emotional pain it brought him.

“O ye men who think or say that I am malevolent, stubborn or misanthropic, how greatly do you wrong me,” it began. “You do not know the cause of my seeming so. From childhood my heart and mind was disposed to the gentle feeling of good will. I was ever eager to accomplish great deeds, but reflect now that for six years I have been in a hopeless case, made worse by ignorant doctors, yearly betrayed in the hope of getting better, finally forced to face the prospect of a permanent malady whose cure will take years or even prove impossible.”

Beethoven, then 32 years old, discussed his suicidal thoughts, but felt he hadn’t produced enough music yet to go peacefully. He never mailed the letter, and it was only found among his things years after his death.

Now, that apartment, where he composed the Tempest sonata and first passes at his Third Symphony known as Eroica, has been expanded and turned into the Beethoven Museum, chronicling the life and work of the composer. Visitors to the museum can see ear pipes (early hearing aid devices) and a projection box that magnified sound when placed on Beethoven’s piano, as well as simulate Beethoven's deafness at an interactive station.

Austrian Theater Museum

The Austrian Theater Museum—filled with more than 2 million stage models, props, costumes, art and documents—is in the former Palais Lobkowitz, named so because it was once home to one of Beethoven’s patrons, Franz Joseph Maximilian, 7th Prince Lobkowitz. In 1799, Lobkowitz set up a festive concert hall, currently known as Eroica Hall, in the palace. Beethoven held several performances here—including a famous piano duel between him and German composer Daniel Steibelt in 1800. It was a piano improvisation contest. Lobkowitz sponsored Steibelt, and Karl Alois, 2nd Prince Lichnowsky, sponsored Beethoven. Steibelt lost spectacularly, and refused to return to Vienna ever again. Four years later, Beethoven performed his Third Symphony, Eroica, at the palace, in its first private performance; he had dedicated it to Lobkowitz after angrily taking the dedication away from Napoleon. Beethoven was furious that Napoleon declared himself emperor, saying it showed he was no different than any other man ignoring human rights. Then, in 1807, Beethoven premiered his Fourth Symphony, also in Eroica Hall. Curiously, Lobkowitz didn’t become an actual patron of Beethoven’s until 1809.

Beethoven’s Grave, Central Cemetery

Beethoven died in 1827—but he was buried three times, finally resting in a grave in Central Cemetery. The first burial was in Währinger Ortsfriedhof, a cemetery a bit outside Vienna proper. He was exhumed in 1863 when his gravesite was repaired; at that time, he was transferred to a more secure metal coffin and then reburied in the same spot. That cemetery closed in 1873, and 15 years later in 1888, Beethoven was exhumed once again. His body was moved to Central Cemetery and placed in a grave of honor, now alongside composers Johannes Brahms, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (though this one’s only a memorial), Franz Schubert and Johann Strauss.

Beethoven's publisher sent a dozen bottles of wine as a gift just before the composer's death, allegedly prompting Beethoven’s last words: “Pity, pity—too late!” And there's a bit of intrigue that surrounds Beethoven’s death, stemming from a letter found posthumously. It was a love letter, addressed to his “Immortal Beloved,” and began with “My angel, my everything, my very self”—but no one knows who the letter was actually for.

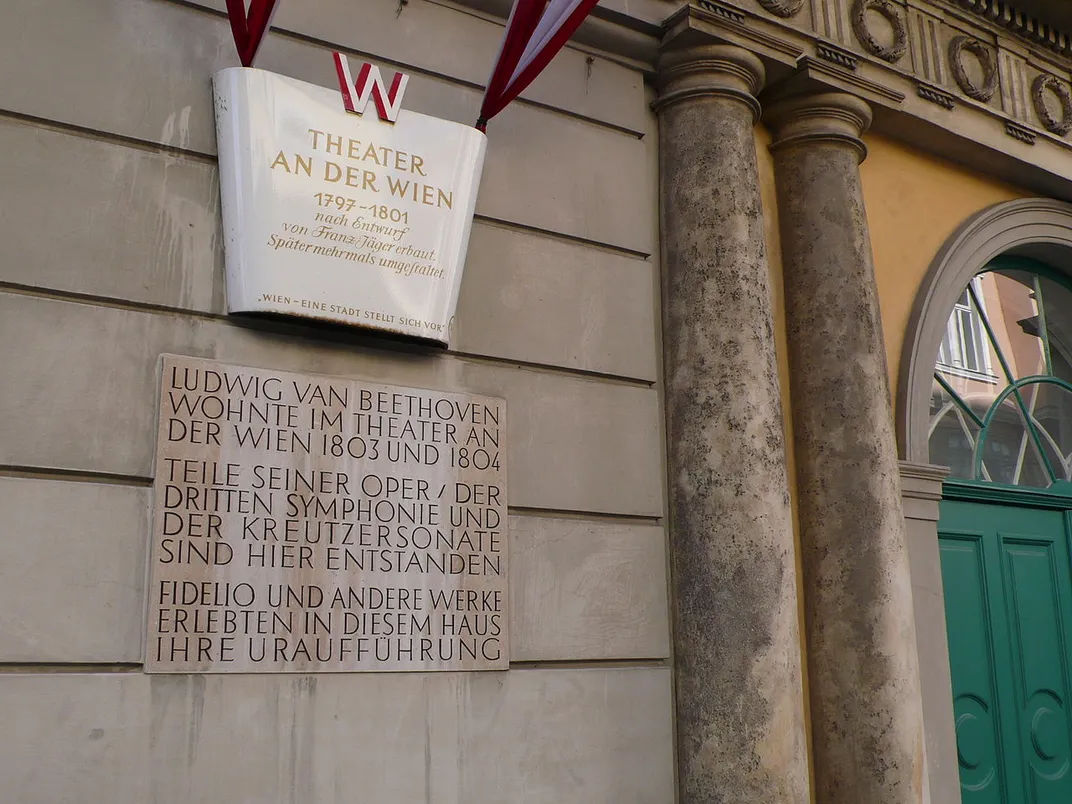

Theater an der Wien

In 1803, composer Emanuel Schikaneder hired Beethoven on as the director of music and resident composer at Theater an der Wien, an opera house that had only been open two years. That same year, Beethoven premiered a few of his compositions there while living on the premises: Christ on the Mount of Olives, the Second Symphony and the Piano Concerto in C Minor. In 1805, while he was still living in the apartment, he also premiered Fidelio (Beethoven’s only opera), Eroica, and other works—sometimes he conducted and sometimes he played piano.

Ignaz von Seyfried, a Viennese composer and Beethoven’s friend, explained what it was like when Beethoven lived at the opera house:

“He liked to go to the opera and see productions multiple times, particularly at the Theater an der Wien which was flourishing so beautifully at the time. Also out of sheer convenience as all he really had to do was walk out of his room and take his place in the arena. In his household a truly admirable confusion … books and music strewn in every corner, there the remains of a cold snack – here sealed or half-empty bottles – there on top of the piano on scrawled sheets the material for a magnificent, still embryonic, symphony [...].”

Currently, the theater is primarly an opera house with its own company. Tours are available, and this year, there will be a series of lectures and performances of Beethoven's works. Sadly, his apartment no longer exists.

Notable Residences

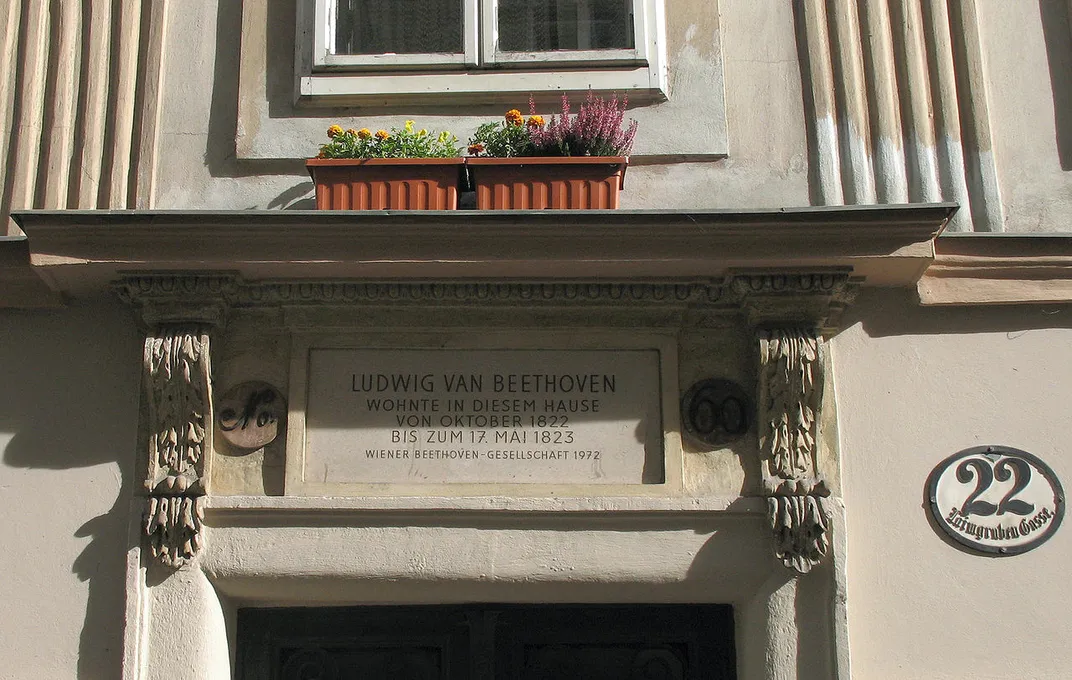

Laimgrubengasse 22

From October 1822 to March 1823, Beethoven lived in the building at Laimgrubengasse 22, in an apartment that faced the courtyard. He used this space to compose parts of some of his most famous works: the Missa Solemnis, the Ninth Symphony and the Piano Sonata in C Minor, op. 111. Today, the building is home to a restaurant named after the composer, Ludwig Van, offering classic and modern interpretations on Viennese cuisine.

Mayer on Pfarrplatz

For a short time in 1817, Beethoven lived in a house at the winery Mayer on Pfarrplatz, which has been producing wine since the 1600s. There, he worked on his Ninth Symphony. The house is now a restaurant within the winery, which honors Beethoven’s legacy by prominently featuring his image on the wine bottles.

Pasqualati House, Mölker Bastei 8

Beethoven spent eight years on and off living on the fourth floor of the Pasqualatihaus, an apartment building owned by Josef Benedikt Baron Pasqualati. Some of the compositions he worked on here include Fidelio; his Fourth, Fifth, Seventh and Eighth symphonies; and some piano pieces—including Fur Elise. The house has a small memorial and museum now (though not in Beethoven’s original apartment, which is off limits to the public) containing some of his personal items, like a salt and pepper pot set and some reproductions of his sheet music.

Beethoven-Grillparzer Haus, Grinzinger Str. 64

In the summer of 1808, Beethoven moved to the house at Grinzinger Strasse 64, where an 18-year-old Franz Grillparzer (one of Austria’s famous writers and poets) lived with his mother. The house is now appropriately called the Beethoven-Grillparzer Haus. While the group lived there, Beethoven would often practice his works on the piano—until an incident with Grillparzer’s mother made him stop. Beethoven’s apartment faced the street; the Grillparzers’ faced the courtyard. There was an entryway and staircase between the two rooms.

“…When [Beethoven] played it was heard all over the house,” Grillparzer said, recounted in the book Memories of Beethoven. “In order to hear it better, my mother often opened the door to the kitchen, which was closer to his lodgings. Once she went out into the vestibule...By chance, Beethoven happened to stop just at that moment and came out of his door into the corridor. When he saw my mother, he hurried back in, came out with his hat on and stormed out and—never played again all summer.”

Though his exit was abrupt that day, the friendship between Beethoven and Grillparzer endured the eavesdropping; Grillparzer even wrote the eulogy for Beethoven’s funeral. When you visit, keep in mind this is a private residence. There’s a commemorative plaque outside noting the home's history.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)