A Brief History of Food as Art

From subject to statement, food has played a role in art for millennia

Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was the first artist in the modern era to think of the preparation and consumption of food as art. The avant-garde Futurist movement, formed by Marinetti and other artists in Milan in 1909, embraced the industrial age and all things mechanical—from automobiles and planes to manufacturing methods and city planning. They thought cooking and dining, so central to everyone’s day-to-day lives, should also be central to their farsighted, far-out ideals.

In 1932, Marinetti published The Futurist Cookbook. It was not merely a set of recipes; it was a kind of manifesto. He cast food preparation and consumption as part of a new worldview, in which entertaining became avant-garde performance. The book prescribed the necessary elements for a perfect meal. Such dining had to feature originality, harmony, sculptural form, scent, music between courses, a combination of dishes, and variously flavored small canapés. The cook was to employ high-tech equipment to prepare the meal. Politics could not be discussed, and food had to be prepared in such a way that eating it did not require silverware.

Marinetti’s musings could not have predicted the role food would come to play in art nearly a century later. Contemporary artists have used food to make statements: political (especially feminist), economic, and social. They’ve opened restaurants as art projects, conducted performances in which food is prepared and served in galleries, and crafted elaborate sculptures from edible materials like chocolate and cheese. Horrifying as it might have seemed to Marinetti, some artists today even embrace food as a rejection of everyone and everything that is future-obsessed.

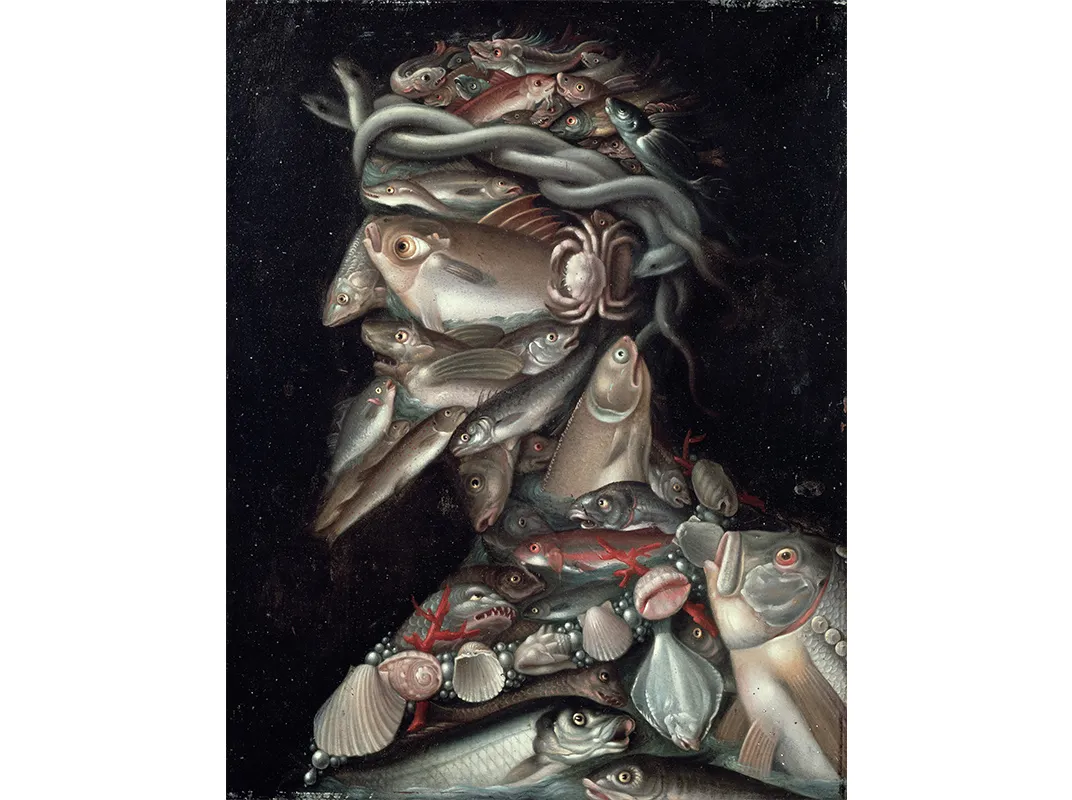

Looking back, food has always played a role in art: Stone Age cave painters used vegetable juice and animal fats as binding ingredients in their paints, and the Egyptians carved pictographs of crops and bread on hieroglyphic tablets. During the Renaissance, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, a painter for the Habsburg court in Vienna, and later, for the Royal Court in Prague, painted whimsical puzzle-like portraits in which facial features were composed of fruits, vegetables, and flowers.

When I think of food and art, intuitively I recall the big, beautiful still lifes of the Dutch golden age that I first encountered in a northern Renaissance art history class. In these glorious paintings, each surface, from the glistening feathered coats of duck carcasses on shiny silver platters to the dewy skin of fruit and berries, is carefully rendered to create the illusion that the feast is sitting right in front of the viewer. In the 1600s, such paintings attested to the owners’ wealth and intellectual engagement. The foods depicted had symbolic significance often related to biblical texts, and how the objects were arranged—and which had been consumed— conveyed a message about the fleeting nature of time or the need for temperance.

As a young artist, I studied Cezanne’s chunky renderings of apples and oranges. For Post-Impressionist painters like Cezanne, observation from life was just the beginning of a largely imaginative process. They valued vivid color and lively brushstrokes over the hyperrealism of the past.

During the pop art era, food became a social metaphor. Wayne Thiebaud painted rows of pies and cakes in bright pastel colors that brought to mind advertisements and children’s toys. Presented like displays at a diner, rather than homely features of private life, his arrangements reflected an itinerant society in which sumptuous desserts signified American abundance.

At around the same time, artists began using real food as an art material. In 1970, the sardonic Swiss-German artist Dieter Roth, also known as Dieter Rot, made a piece titled “Staple Cheese (A Race)”—a pun on “steeplechase”—that comprised 37 suitcases filled with cheese, and other cheeses pressed onto the walls with the intention that they would drip, or “race,” toward the floor. A few days after the exhibition opened in Los Angeles, the exhibition gave off an unbearable stench. The gallery became overrun with maggots and flies, and public health inspectors threatened to close it down. The artist declared that the insects were in fact his intended audience.

The feminist artists of the late 1960s and early 1970s regarded the American relationship with food in terms of the constraints it put on women. Feminists asserted that the personal—including the most mundane aspects of daily life—was political. In 1972, Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago rented a vacant 17-room house in Los Angeles that was scheduled for demolition and turned it into a massive art installation. Schapiro and other female artists created an immersive installation in the dining room, mimicking the process girls follow when decorating dollhouses. Their project, both a performance and an installation, condemned society’s double standard—the disparity in expectations and opportunities for men and women. While boys were trained to succeed in the world, girls were expected to keep house for their husbands. Later, feminist artists like Elizabeth Murray would suggest that women are sufficiently powerful to handle both the worldly and the domestic in works like “Kitchen Painting” (1985), in which a globby spoon bound to a figure presiding over a kitchen seems to bolt from the picture plane and confront the viewer.

In 1974, Chicago riffed on the dining room theme again when she began “The Dinner Party,” a conceptual tour de force now housed in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, at the Brooklyn Museum. With a team of talented artisans, over the course of several years, Chicago crafted a 48-foot-long triangular dinner table with place settings for 39 culturally notable women, some real and some mythical, from prehistory to the modern women’s movement. Each setting includes a handmade napkin, a ceramic plate, a goblet, and a runner, all with iconography customized for the specific woman. As the time line converges on the present, the plates become more and more three-dimensional, symbolizing women’s growing freedom and political power.

During the 1990s, many artists became attuned to the personal alienation that would result from the introduction of the home computer and other screen-based activities. To remedy nascent anomie, some inaugurated the discipline of “relational aesthetics”—now known less opaquely as “social sculpture”—according to which human interaction, including eating together, was conceived as an art form in itself. One of the most prominent practitioners was Rirkrit Tiravanija, who began cooking and serving food to viewers at galleries, leaving the pots, pans, and dirty dishes in the gallery for the duration of his exhibitions.

Today, beginning artists still learn to paint still lifes of fruit and vegetables. Many later turn away from painting to pursue newer, more experimental media, but food-centered artists often continue to believe in the power of pigment on canvas. New York–based painters Gina Beavers, Walter Robinson, and Jennifer Coates are good examples. Beavers combs the Internet for photographs of food, which she then combines into multi-image collages and paintings on large canvases. Robinson is pre-occupied with whiskey, cheeseburgers, and other objects of longing. Coates focuses on junk food, making paintings in which s’mores, mac ‘n’ cheese, and pizza take on abstract forms. Overall, there’s a healthy tension between tradition and iconoclasm in contemporary food art. Some 85 years after its publication, Marinetti’s cookbook still seems ahead of the curve, though perhaps not too far ahead.

Related Reads

Arcimboldo

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.