Frank Lloyd Wright Buildings Nominated for Unesco World Heritage Status

It’s the first time the United States has nominated works of modern architecture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b3/e1/b3e150b4-6a49-4204-8d19-4414b92c1d21/rc001949.jpg)

Recognizing the international appeal and historic value of Frank Lloyd Wright's work, the United States has nominated ten of the architect's buildings for inclusion on the Unesco World Heritage List. This is the first time the United States has nominated examples of modern architecture and the first time it has nominated a new site since 2013. The ten sites span Wright's prodigious career, from his early Prairie period to his final buildings, and are located in seven states. According to Unesco, the World Heritage List seeks to recognize sites whose importance stretches beyond their home country, and whose "outstanding universal value” represents the best the built and natural world has to offer.

From the instantly recognizable Fallingwater home in Pennsylvania to Wright's only skyscraper, the ten sites create a snapshot of the architect's work. "They are the most iconic, fully realized and innovative of more than 400 existing works by Frank Lloyd Wright," the architect's foundation said in a press release. "Each is a masterwork and together they show varied illustrations of 'organic architecture' in their abstraction of form, use of new technologies and masterful integration of space, materials and site."

Individually, each of the sites have already been designated a U.S. Historic Landmark. Though inclusion on the Unesco list does not guarantee any special protection, it does encourage tourism, which can boost local economies and be potentially funneled back into preservation.

A few examples of modern architecture already on the Unesco list include Jørn Utzon's Sydney Opera House, the White City of Tel Aviv, the Bauhaus School in Germany and seven buildings from Spanish architect Antoni Gaudí. There are currently 1,007 World Heritage Sites, though only 22 in the United States. To gain inclusion on the list, the Frank Lloyd Wright sites will have to go through a vetting process that includes a series of site visits by two separate advisory boards, the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) and the World Conservation Union (IUCN), all meant to determine the universal value of the buildings.

In addition to proving "outstanding universal value," any heritage site must also meet at least one of ten seperate criteria dictated by the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. These criteria include representing "a masterpiece of creative genius," exhibiting "an important interchange of human values," bearing "unique testimony" to a culture or civilization and being an outstanding example of a "significant stage in human history," among others.

"Wright was the father of modern architecture, fundamentally redefining the nature of form and space during the early 20th century in ways that would have enduring impact on modern architecture worldwide," Richard Longstreth, president of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, said in a press release.

Once the vetting process is complete, the sites could be added to the list as early as the summer of 2016.

Unity Temple (1905, Oak Park, Illinois)

Unity Temple is the only remaining public example of Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie style, characterized by low, horizontal lines meant to blend in with flat landscapes, which spanned 1900 to 1919. The Universalist church was built in 1905 in Oak Park, Illinois; Wright was chosen to design it because he was a Unitarian Universalist himself, and his uncle had been a famous preacher within the congregation.

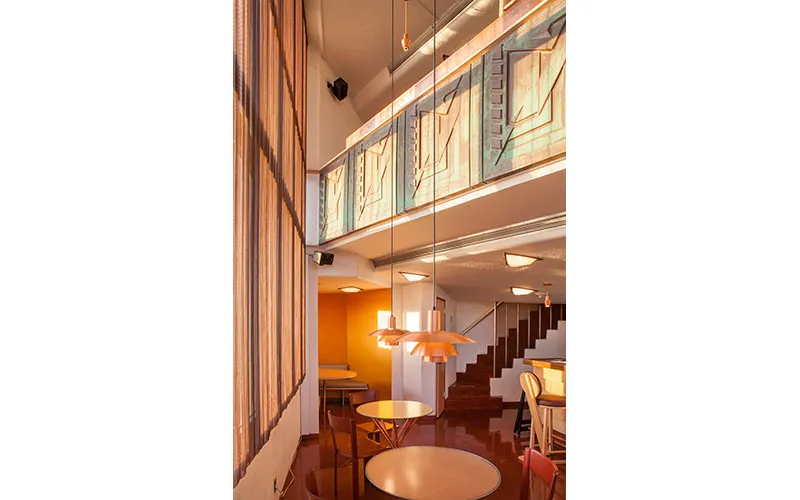

Wright wanted to create a space inspired by the Unitarian Transcendentalists, who encouraged looking inward, to the congregation, for spiritual guidance, rather than outward. His design was limited by a modest budget and urban location. To stay within his budget, Wright used an unconventional material: exposed, poured-in-place reinforced concrete—historically reserved for industrial buildings, not places of worship. The building's cubic exterior contrasts with the almost airy interior, which includes two sky-lit spaces, one for worship and one for social gatherings. The building was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1970.

Frederick C. Robie House (1908, Chicago, Illinois)

The most famous private home Wright designed during his Prairie period is arguably the Frederick C. Robie House, built in Chicago in 1909. Considered a masterpiece of Prairie style, the Robie House is conceived as a single unit—from the exterior to the furniture, all the elements are connected. Wright relied heavily on horizontal lines, meant to evoke the horizon of the Midwestern prairie. The dining room and living room were designed to be a single, open, flowing space, a radical design notion for the early 1900s.

Though considered for demolition in the 1940s and 1950s, today the building is owned by the University of Chicago and operates as a museum run by the Frank Lloyd Wright Trust. In 1991, the American Institute of Architects recognized the Robie House as one of the ten most significant buildings of the 20th century.

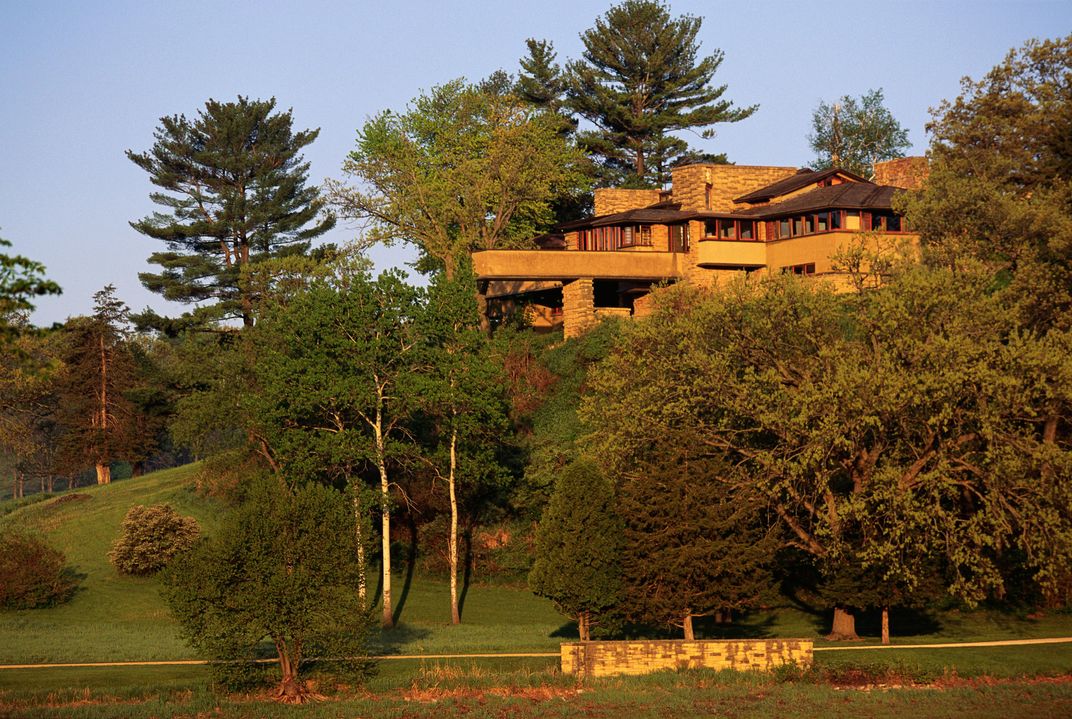

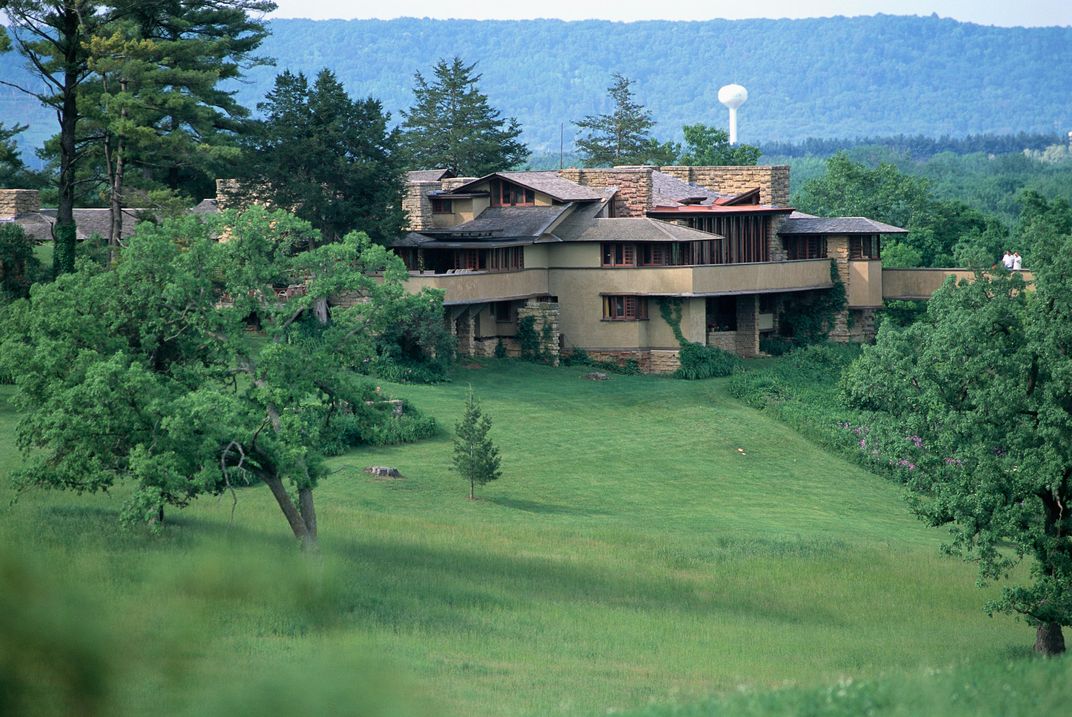

Taliesin (1911, Spring Green, Wisconsin)

Taleisin, first built beginning in 1911 in Spring Green, Wisconsin, was Frank Lloyd Wright's personal home and studio for almost half a century, covering 600 acres in the green hills of Wisconsin. The site was destroyed twice by fire—including one blaze in 1914 that killed his mistress along with two of her children and four others. Wright saw each destruction as a chance to rebuild the estate. Most of the rooms are entered at a corner, drawing the visitor's eye to the wide interior space and windows, which display the Wisconsin countryside beyond.

Today, the house is both a museum and an architecture school. Managed by the non-profit Taliesin Preservation, the home was named a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

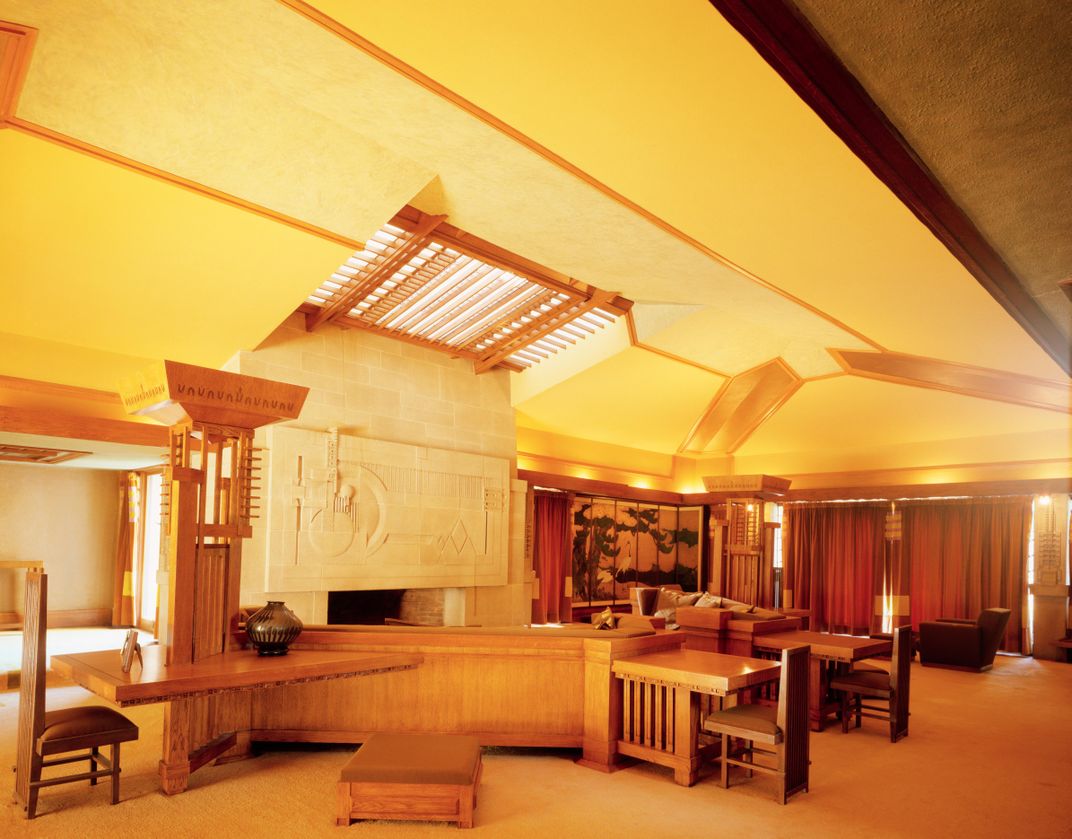

Hollyhock House (1918, Los Angeles, California)

Commissioned by oil heiress and experimental producer (and noted bohemian free spirit) Aline Barnsdall in 1918, the Hollyhock House was Wright's first commission in Southern California. While designing the house, Wright drew inspiration from the traditional forms of Spanish California and Pre-Columbian Mexico—in the years prior, he had become fascinated with the temples of Uxmal and Chichén Itzá, which he had first seen in photographs at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in 1915. Wright's fascination with these forms is reflected in the home's monolithic, temple-like structure and its construction material, which is meant to look like solid stone (it's actually plaster over lath). The building opens toward a central courtyard encircled by rooftop terraces. Barnsdall wanted a space whose many rooms would serve as not only a personal residence but as a theater, studio and home for actors. Though she only lived in the building until 1927, the house has served many purposes throughout its life, from an art gallery to a U.S.O. facility.

Since the mid-1970s, the home has functioned as a public museum. Recently, it underwent a massive restoration, spanning six years and costing $4 million. The house was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007.

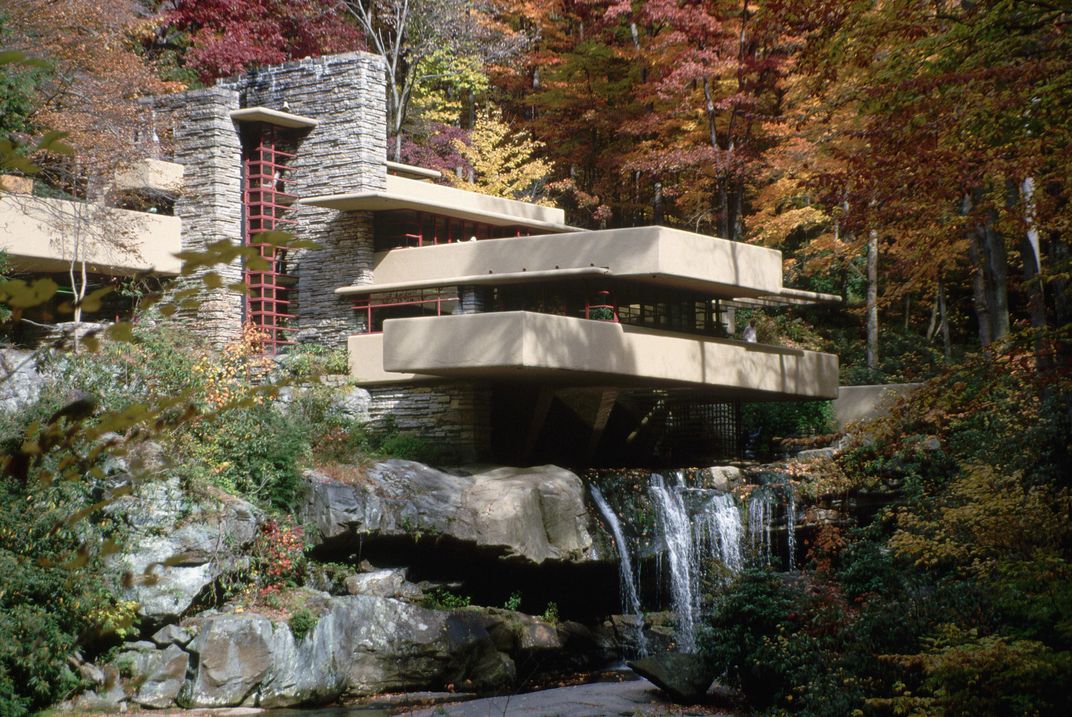

Fallingwater (1935, Mill Run, Pennsylvania)

Considered one of the country's most beautiful houses—and one of Wright's most iconic works—Fallingwater was built between 1936 and 1939 in the mountains of western Pennsylvania. Commissioned by the Kaufmanns, a wealthy Pittsburgh family, it was meant to provide them with a peaceful, secluded escape from the dirt and grime of the city.

Built along Bear Run, a mountain stream, the house is perched on top of a waterfall. Wright wanted the family to have more than just a view of the falls—he wanted them to live in it, and experience its sound on a daily basis. The house, which cost $155,000 to build, was featured on the cover of TIME magazine in 1938. It provided the family with a private residence until the 1960s; in 1964, it opened to the public as a museum.

Herbert and Katherine Jacobs House (1936, Madison, Wisconsin)

Built as a modest home for a typical family, the house Wright designed for Herbert and Katharine Jacobs was constructed in 1937 on the outskirts of Madison. The building is small—just 1,550 square feet—and composed of board walls, bricks and glass doors. Though small, the interior was designed to feel spacious, and it opens toward a terrace and garden, creating a continuous sense of flow between the inside and outside. Today, the house is a private residence, though tours are available by appointment. The American Institute of Architects ranked it as one of the 20 most influential residential designs of the 20th century.

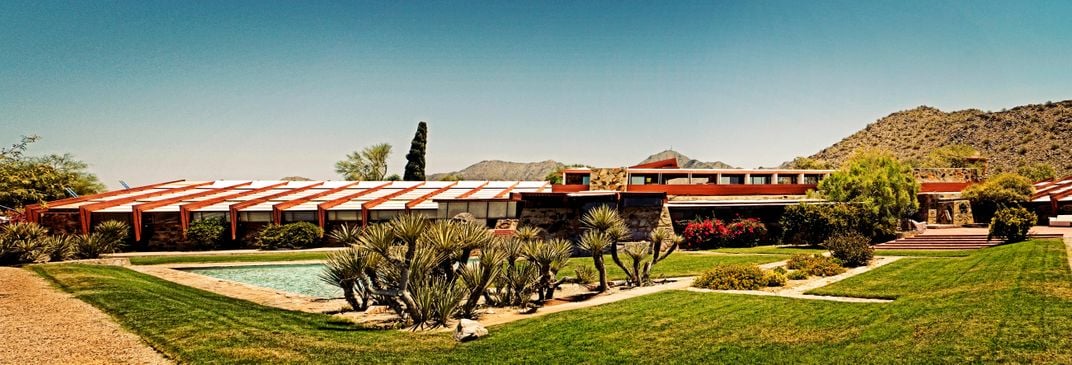

Taliesin West (begun 1938, Scottsdale, Arizona)

Tiring of the cold Wisconsin winters, Wright chose to build his winter home and studio, dubbed Taliesin West, outside Phoenix in Scottsdale, Arizona—a project that took the last 20 years of his life to complete. He used the property as a sort of testing ground for new materials and designs—all inspired by the desert—which he would then incorporate into designs for clients. (Desert stones and boulders, for example, were employed to create a type of "desert masonry.") Today, the building houses the offices of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, as well as the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. Named a National Historic Landmark in 1982, it is open year-round to visitors.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (1943, New York, New York)

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City was meant to match the modernity of the art it would house: The building itself is a sculpture, with spiral ramps leading upward toward a sky-lit dome. Though the building has undergone a few modifications—and an addition—since it was completed in 1959, it remains true to Wright's initial vision. "A monument to modernism ... " reads the Guggenheim's website, which also calls it "arguably the most important building of Wright's late career." Today, the museum is one of New York City's most popular attractions, with more than one million visitors annually.

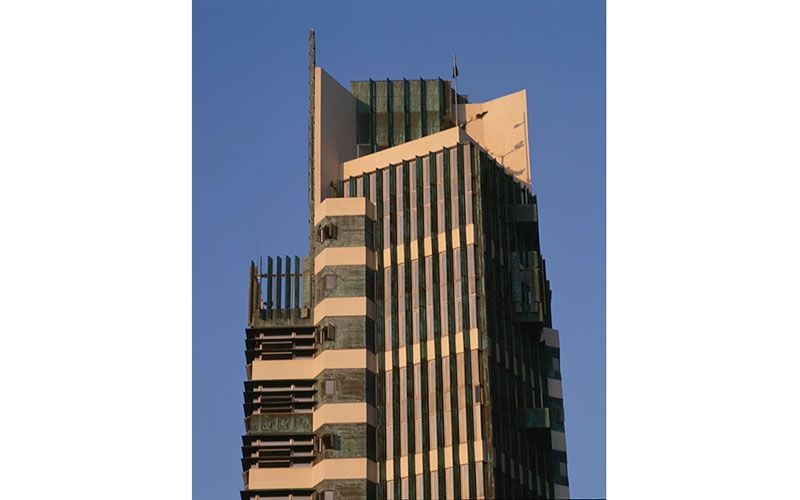

Price Tower (1952, Bartlesville, Oklahoma)

Despite the fact that he designed hundreds of buildings throughout his career, only one of Wright's free-standing skyscrapers was ever completed: the Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. As with all his designs, Wright's skyscraper reimagined the form—using the shape of a tree as his inspiration, Wright conceived of a central "trunk" and floors that project out almost like branches. The 19-story building was originally supposed to be only two stories, but Wright convinced Oklahoma oil baron Hal Price to agree to a taller structure. Designed for mixed-use, with room for commercial and residential spaces, the building has changed little from its original plan.

Marin County Civic Center (1957, San Rafael, California)

Wright's last major work was the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael, California, which was completed in 1957, just two years before his death. Wright designed the center to, in his own words, "melt into the sunburnt hills" that surround it. "We know that the good building is not the one that hurts the landscape, but is one that makes the landscape more beautiful than it was before that building was built," he said of the project.

The only one of Wright's buildings to have been built for government use, the center is comprised of two buildings—one for the county's administration, and one for its courts. The buildings are set at a slight angle to one another and connected by a circular rotunda; circular forms are utilized throughout the center, from gold spheres that line the roofline to circular courtrooms. The Civic Center was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1991.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)