From Brooklyn to Worthington, Minnesota

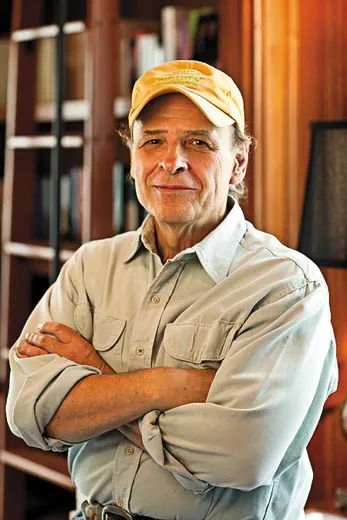

Novelist Tim O’Brien revisits his past to come to terms with his rural hometown

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/My-Town-Worthington-MN-cornfield-631.jpg)

From the year of his birth in 1914 until the outbreak of war in 1941, my father lived in a mostly white, mostly working-class, mostly Irish Catholic neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York. He was an altar boy. He played stickball and freeze tag on safe, tree-lined streets. To hear my dad talk about it, one would've thought he had grown up in some long-lost Eden, an urban paradise that had vanished beneath the seas of history, and until his death a few years ago, he held fast to an impossibly idyllic, relentlessly romanticized Brooklyn of the 1920s and '30s. No matter that his own father died in 1925. No matter that he went to work as a 12-year-old to help support a family of five. No matter the hardships of the Great Depression. Despite everything, my dad's eyes would soften as he reminisced about weekend excursions to Coney Island, apartment buildings festooned with flower boxes, the aroma of hot bread at the corner bakery, Saturday afternoons at Ebbets Field, the noisy bustle along Flatbush Avenue, pickup football games on the Parade Grounds, ice-cream cones that could be had for a nickel and a polite thank-you.

Following Pearl Harbor, my father joined the Navy, and soon afterward, without the dimmest inkling that he had stepped off a great cliff, he left behind both Brooklyn and his youth. He served on a destroyer at Iwo Jima and Okinawa, met my mother in Norfolk, Virginia, got married in 1945, and, for reasons still unclear to me, set off with my mom to live amid the corn and soybeans of southern Minnesota. (True, my mother had grown up in the area, but even so, why didn't they settle in Brooklyn? Why not Pasadena or even the Bahamas?)

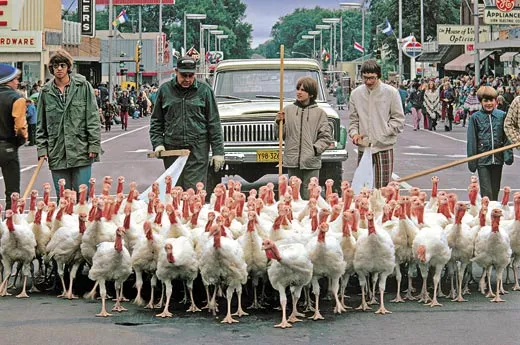

I showed up in October 1946, part of an early surge that would become a great nationwide baby boom. My sister, Kathy, was born a year later. In the summer of 1954, after several years in Austin, Minnesota, our family moved across the state to the small, rural town of Worthington, where my dad became regional manager for a life insurance company. To me, at age 7, Worthington seemed a perfectly splendid spot on the earth. There was ice skating in winter, organized baseball in summer, a fine old Carnegie library, a decent golf course, a Dairy Queen, an outdoor movie theater and a lake clean enough for swimming. More impressively, the town styled itself Turkey Capital of the World, a title that struck me as both grand and a bit peculiar. Among the earth's offerings, turkeys seemed a strange thing to boast about. Still, I was content for the first year or two. I was very close to happy.

My father, though, did not care for the place. Too isolated. Too dull and pastoral. Too far removed from his big-city youth.

He soon began drinking. He drank a lot, and he drank often, and with each passing year he drank more. Over the next decade he twice ended up in a state treatment facility for alcoholics. None of this, of course, was the fault of the town, any more than soybeans can be faulted for being soybeans. Rather, like a suit of clothes that may fit beautifully on one man but too snugly on another, I have come to believe that Worthington—or maybe the rural Midwest in general—made my dad feel somehow limited, consigned to a life he hadn't planned for himself, marooned as a permanent stranger in a place he could not understand in his blood. An outgoing, extravagantly verbal man, he now lived among famously laconic Norwegians. A man accustomed to a certain vertical scale to things, he lived on prairies so flat and so unvaried that one spot could be mistaken for any other. A man who had dreamed of becoming a writer, he found himself driving down lonely farm lanes with his insurance applications and a halfhearted sales pitch.

Then, as now, Worthington was a long way from Brooklyn, and not just in the geographical sense. Tucked into the southwestern corner of Minnesota—12 miles from Iowa, 45 miles from South Dakota—the town was home to about 8,000 people when our family arrived in 1954. For centuries the surrounding plains had been the land of the Sioux, but by the mid-1950s not much remained of that: a few burial mounds, an arrowhead here and there, and some borrowed nomenclature. To the south was Sioux City, to the west Sioux Falls, to the northeast Mankato, where on December 26, 1862, a group of 38 Sioux were hanged by the federal government in a single mass execution, the result of a bloody revolt earlier that year.

Founded in the 1870s as a railroad watering station, Worthington was an agricultural community almost from the start. Tidy farms sprang up. Sturdy Germans and Scandinavians began fencing in and squaring off the Sioux's stolen hunting grounds. Alongside the few surviving Indian names—Lake Okabena, Ocheyedan River—such solidly European names as Jackson and Fulda and Lismore and Worthington were soon transposed to the prairie. Throughout my youth, and still today, the town was at its core a support system for outlying farms. No coincidence that I played shortstop for the Rural Electric Association's Little League team. No coincidence that a meatpacking plant became, and remains, the town's primary employer.

For my father, still a relatively young man, it had to be bewildering to find himself in a landscape of grain elevators, silos, farm implement dealerships, feed stores and livestock sales barns. I don't mean to be deterministic about it. Human suffering can rarely be reduced to a single cause, and my dad may well have ended up with similar problems no matter where he lived. Yet unlike Chicago or New York, small-town Minnesota did not allow a man's failings to disappear beneath a veil of numbers. People talked. Secrets did not stay secret. And for me, already full of shame and embarrassment at my dad's drinking, the humiliating glare of public scrutiny began eating away at my stomach and at my self-esteem. I overheard things in school. There was teasing and innuendo. I felt pitied at times. Other times I felt judged. Some of this was imagined, no doubt, but some was as real as a toothache. One summer afternoon in the late '50s, I heard myself explaining to my teammates that my dad would no longer be coaching Little League, that he was in a state hospital, that he might or might not be back home that summer. I did not utter the word "alcohol"—nothing of the sort—but the mortification of that day still opens a trapdoor in my heart.

Decades later, my memories of Worthington are as much colored by what went on with my father—his increasing bitterness, the gossip, the midnight quarrels, the silent suppers, the bottles hidden away in the garage—as by anything having to do with the town itself. I began to hate the place. Not for what it was, but for what it was to me, and to my dad. After all, I loved my father. He was a good man. He was funny and intelligent and well read and conversant in history and a terrific storyteller and generous with his time and great with kids. Yet every object in town seemed to shimmer with an opposite judgment. The water tower overlooking Centennial Park seemed censorious and unforgiving. Main Street's Gobbler Café, with its crowd of Sunday diners fresh from church, seemed to hum with a soft, persistent rebuke.

Again, this was partly an echo of my own pain and fear. But pain and fear have a way of influencing our attitudes toward the most innocent, most inanimate objects in the world. Places are defined not just by their physicality, but also by the joys and tragedies that transpire in those places. A tree is a tree until it is used for a hanging. A liquor store is a liquor store until your father almost owns the joint. (Years later, as a soldier in Vietnam, I would encounter this dynamic again. The paddies and the mountains and the red clay trails—all of it seemed to pulse with the purest evil.) After departing for college in 1964, I never again lived in Worthington. My parents stayed on well into their old age, finally moving in 2002 to a retirement community in San Antonio. My dad died two years later.

A few months ago, when I paid a return visit to Worthington, a deep and familiar sadness settled inside me as I approached the town on Highway 60. The flat, repetitive landscape carried the feel of eternity, utterly without limit, reaching off toward a vast horizon just as our lives do. Maybe I was feeling old. Maybe, like my father, I was conscious of my own lost youth.

I stayed in Worthington only a short while, but long enough to discover that much had changed. In place of the almost entirely white community of 50 years ago, I found a town in which 42 languages or dialects are spoken, a place teeming with immigrants from Laos, Peru, Ethiopia, Sudan, Thailand, Vietnam and Mexico. Soccer is played on the field where I once booted ground balls. On the premises of the old Coast to Coast hardware store is a thriving establishment called Top Asian Foods; the Comunidad Cristiana de Worthington occupies the site of a restaurant where I once tried to bribe high-school dates with Cokes and burgers. In the town's phone book, alongside the Andersons and Jensens of my youth, there were such surnames as Ngamsang and Ngoc and Flores and Figueroa.

The new, cosmopolitan Worthington, with a population of around 11,000, did not arise without tensions and resentments. A county Web page listing incarcerations contains a hefty percentage of Spanish, Asian and African names, and, as might be expected, few newcomers are among Worthington's most prosperous citizens. Barriers of language and tradition haven't completely vanished.

But the sadness I'd felt on returning home was replaced by a surprised, even shocked admiration for the community's flexibility and resilience. (If towns could suffer heart attacks, I would've imagined Worthington dropping stone-dead at such radical change.) I was astonished, yes, and I was also a little proud of the place. Whatever its growing pains and residual problems, the insular, homogenized community of my youth had managed to accept and accommodate a truly amazing new diversity.

Near the end of my visit, I stopped briefly in front of my old house on 11th Avenue. The day was sunny and still. The house seemed deserted. For a while I just sat there, feeling all kinds of things, half hoping for some closing benediction. I suppose I was seeking ghosts from my past. Maybe a glimpse of my dad. Maybe the two of us playing catch on a summer afternoon. But of course he was gone now, and so was the town I grew up in.

Tim O'Brien's books include Going After Cacciato and The Things They Carried.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.