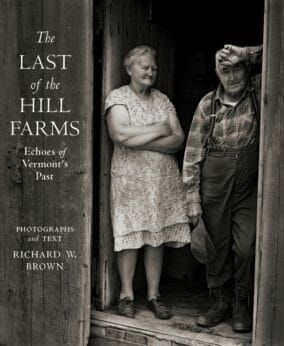

This Photographer Spent 46 Years Documenting the Vanishing World of Vermont’s Remote Northeast Kingdom

Photographer Richard Brown moved to Vermont’s remote Northeast Kingdom in 1971, then spent the next 46 years (and counting) documenting the region’s agricultural community. Brown’s book, The Last of the Hill Farms, chronicles a way of life long since vanished.

I have always been drawn to the closeness of Vermont’s past.

When I was a kid, my family took trips to the state’s Northeast Kingdom to camp on Burke Mountain. Winding up Route 5, I became aware of the uncommon views passing by our car windows. Derelict tractors rusted away at the edges of fields. Tethered goats grazed on lawns. I thought they were the most beautiful things I’d ever seen. I wished that someday I could live in one of those farmhouses and that this paradise would never change.

The first wish came true. In 1971, I moved to a small village here and started photographing the land and people. Back then, the 20th century still stretched thinly over its predecessor, and I was able to catch glimpses of a bygone era lurking just beneath the surface. At dawn’s light, I would set out, my VW loaded with a couple of Nikons, an 8-by-10 view camera, a tripod and a dozen sheet-film holders. No map. No plan. I might head for North Danville and eventually come out in Greensboro Bend, never encountering a paved road. The idea was to get lost and maybe end up somewhere before 1900—or somewhere that at least looked that way.

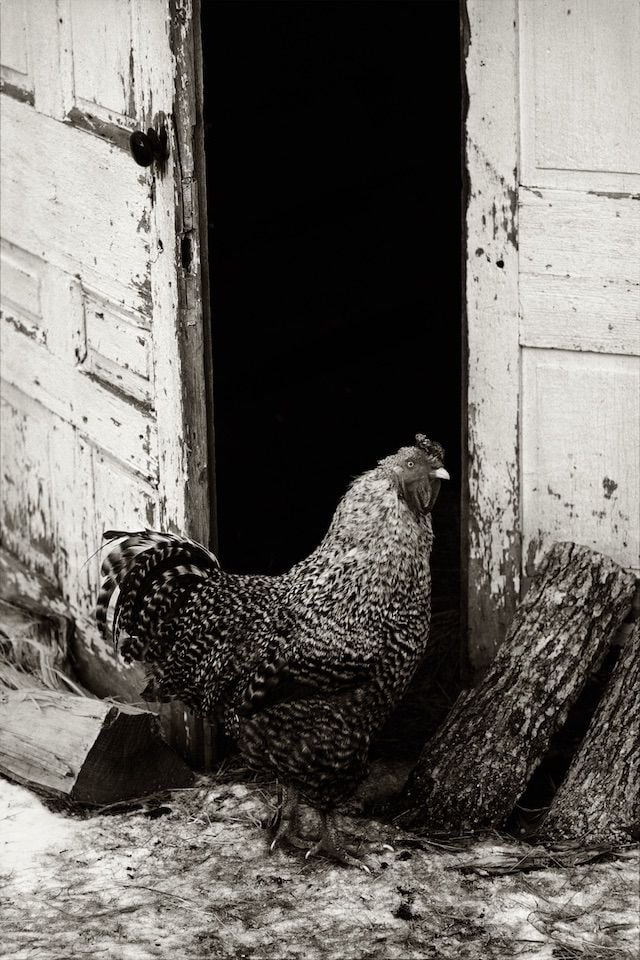

The small homesteads scattered along these back roads represented the last of Vermont’s hill farms. Anyone tired of cultivating rock-strewn ground had left. Those who stayed and worked Vermont’s stubborn hills did so with a quiet yet fierce attachment. They inhabited old houses that creaked and moaned when the mercury hit 30-below, amid familial relics: cane-seated chairs missing legs, cracked ironstone china, sap yokes and grain cradles. Dirt-floored basements held canned applesauce, mustard pickles, and stewed tomatoes glinting in rows on sagging wooden shelves. Winters were spent cutting firewood. A long mud season meant enough income from maple syrup to cover taxes. And on autumn mornings, the sharp fragrance of woodsmoke and rotted manure laced the air, and the maples began to blaze.

I felt like I’d died and gone to photographer’s heaven. It was too good to last. But during that brief interval, while the ghosts of the Northeast Kingdom remained palpable, my camera bore witness to the worn-out and obsolete; the Jersey cows and Belgian draft horses; the ancestral portraits hung from crumbling plaster; and the region’s latest strata of human geology, farmers who faced my lens with forbearance and rough-hewn dignity. Photographs capture moments. Moments that reach backward, not forward. In a 60th of a second, the blink of an eye, the click of a shutter, past and present collide. The image that glows on the ground glass is captured forever in silver.

More stories from Modern Farmer:

- 7 Presidents Who Farmed

- Where Have All the Womyn Farmers Gone?

- The Strange, Horrifying History of Cherry Research Farm in North Carolina

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/be/23/be2322e5-89c2-4ee1-9d01-841be74499bf/theronboyd_thelastofthehillfarms.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/51/81510931-08cf-4d91-9620-7e65dc36a5f8/milopersons_thelastofthehillfarms-768x946.jpg)