Full Speed Ahead

A railroad, finally, crosses Australia’s vast interior—linking not only the continent’s south with its north, but also its past to its future

Early on a warm January morning, I boarded a freight train emblazoned with aboriginal designs in Adelaide on Australia’s south-central coast, bound for Darwin, 1,800 miles away. Ours would be the first train ever to cross the length of the Australian continent, and as we clattered toward Australia’s desert interior, huge crowds of people, whites and Aborigines alike, lined the tracks to wave and cheer. They jammed overpasses. They stood under eucalyptus trees or atop utes, as Australians call pickup trucks. They clambered onto rooftops. Schoolchildren waved flags, mothers waved babies and, as the train rushed under a bridge, a blind man waved his white stick jubilantly above his head.

The first hours of the journey took us through the wheatgrowing district of South Australia. The harvest was in, and the fields were covered in fawn-colored stubble. Near Quorn, a tornado spiraled up, like a white cobra, scattering chaff across the ground. As we approached the Flinders Ranges, a wall of rock that glowed purple in the evening light, a ute appeared at the side of the track with a man and a woman standing on the back. They held up hand-lettered signs. Hers said, “AT.” On his was written: “LAST.”

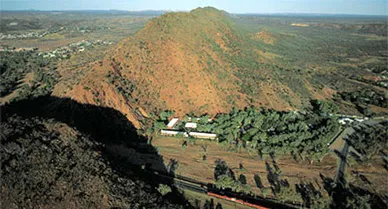

Trains have been rolling between Adelaide and Alice Springs, an oasis of 28,000 in the heart of the continent, since 1929, so our journey wouldn’t officially make history until we traveled beyond The Alice, as the town is known locally. But that didn’t seem to matter to the exuberant crowds, nor to the local politicians who gave speeches at each stop, taking their cue from Prime Minister John Howard, who had hailed the train as a “nation-building project.” Although 90 percent of the country’s population lives in coastal cities, making Australians the most urban people on the planet, the red center, as the desert interior is known, has always been their defining landscape. “We’re so aware of the emptiness,” says Adelaide-based economist Richard Blandy. “To cross that emptiness is emotionally significant for Australians.”

Australians have been dreaming of a railway across the red center since an Adelaide businessman first proposed it in 1858. The government promised to build it in 1911, but droughts, two world wars, economic downturns and doubts about its viability kept the project on the drawing board. Finally, in 1999, government and business leaders got behind the $965 million land bridge from the prosperous south to the increasingly important north, home to vast natural resources and a gateway to Australia’s trading partners in Asia. (In March 2003, ten months before our train rolled, Australia and East Timor agreed to divvy up an estimated $37 billion worth of fossil fuels in the waters between them.)

The transcontinental also has a military function. The Northern Territory has always been the most vulnerable part of the continent; Darwin is closer to Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, than to Australia’s capital, Canberra. To counter today’s threats—particularly from terrorist groups operating within Indonesia—the railway will provide supplies to a squadron of F/A-18’s based near the town of Katherine and also to the armed forces, many of which are based in the Northern Territory.

More broadly, says Australian historian Geoffrey Blainey, “there’s something symbolic about a railway. A road usually follows bush trails or other paths, but a railway is created in one grand gesture. We’re a visual people, and a line drawn across the map, almost dead center, captures the imagination.” Says Mike Rann, the premier of the state of South Australia: “Australians tell stories about their ancestors and the outback. So this train is not just about the future. It helps tell the story of our past, as well. It helps tell the Australian story.”

“Ok, fellas,” said Geoff Noble, the locomotive engineer, “let’s make some history!” We were stopped a few miles south of Alice Springs, on the second day of our journey, and I could hear the high-pitched whine of crickets, like a dentist’s drill, and feel the heat hammering down on the cab. He eased the throttle of the 3,800-horsepower diesel into gear, and we began moving again.

Among the crowd waiting to greet us as we got off the train in Alice Springs were camels decked with brightly colored saddlebags, tended by a bearded man in a blue turban and flowing robes. He was Eric Sultan, a descendant of one of the cameleers who helped found the town in the late 19th century. Camels first caught on as pack animals in the Australian desert beginning in 1840, and by 1910 some 12,000 had been brought in, mostly from Peshawar in present-day Pakistan. The camels hauled wool and gold, supplied cattle ranches and aboriginal missions, and helped build both the Overland Telegraph in 1871 and the first railway from Adelaide to Oodnadatta in the 1880s.

By the 1930s, the internal combustion engine had put the cameleers out of business; they turned their animals loose, and today there are some 650,000 feral camels in central Australia. They’ve long been regarded as a nuisance, because they trample fences and compete with cattle for food. Now, in an ironic twist, an Alice Springs company has begun shipping the animals to countries in the Middle East.

The Aborigines, Australia’s indigenous people, settled on the continent at least 24,000 years ago from Papua New Guinea. According to aboriginal legend, the landscape was formed by creatures such as the Euro, a large kangaroo, that traveled particular routes, known as songlines. Asongline can stretch for hundreds, even thousands, of miles, passing through the territory of several different clans or family groups. Each aboriginal clan must maintain its part of the songline by handing down the creation stories.

Before the first bulldozer began work on the transcontinental railroad, local authorities commissioned a survey of the aboriginal sites that would be affected. Every sacred site and object identified by the survey was bypassed. To avoid a single corkwood tree, an access road was shifted some 20 yards. To protect an outcrop of rock called Karlukarlu (or as it’s known in English, the Devil’s Marbles), the entire rail corridor was moved several miles to the west.

As a result of this flexibility, aboriginal communities have largely embraced the railroad and liken it to a songline. “It’s two lines going side by side,” said Bobby Stuart, an elder of central Australia’s Arrernte people. “There’s the white line. And there’s the aboriginal line. And they’re running parallel.”

The Northern Territory has the highest concentration of indigenous people in Australia: almost 60,000 out of a total state population of about 200,000. Thanks to the Aboriginal Land Rights Act of 1976, the Aborigines now own 50 percent of the Northern Territory, giving them an area roughly equivalent in size to the state of Texas. But poverty and prejudice have kept them exiles in their own country.

Near Alice Springs is an aboriginal housing project of some 20 cinder block dwellings, the Warlpiri camp, where men and women sleep on filthy mattresses on porches. There are flies everywhere. Mangy dogs root among the garbage. Burned-out wrecks of cars lie with doors ripped off and windshields smashed.

The Aborigines’ plight is Australia’s shame. For the first hundred years of white settlement, they were regarded as animals, and were shot, poisoned and driven from their land. During much of the 20th century, government officials routinely separated aboriginal children from their families, moving them into group institutions and foster homes to be “civilized.” Aborigines were not granted the right to vote until 1962. The first Aborigine didn’t graduate from an Australian university until 1966.

Sweeping civil rights legislation in 1967 marked the beginning of a slow improvement in their status, but aboriginal life expectancy is still 17 years less than the rest of the population. (In the United States, Canada and New Zealand, which also have relatively large indigenous populations, life expectancy of indigenous people is three to seven years less than that of the general population.) Aboriginal rates of tuberculosis rival those of the third world. Rheumatic fever, endemic in Dickens’ London, is common. Diabetes, domestic violence and alcoholism are rife. “There are dozens of places here in the Northern Territory where there is no reason for people to get out of bed in the morning,” says Darwin-based historian Peter Forrest, “except perhaps to play cards or drink a flagon of wine.”

They are so disenfranchised that on my journey in the Northern Territory, no Aborigine sold me a book, drove me in a taxi, sat next to me in a restaurant or put a chocolate on my hotel pillow. Instead, I saw aboriginal men and women lying in the street at midday, apparently passed out from drinking, or sitting on the ground staring into space as white Australians hurried past.

The transcontinental railroad has sent a ray of hope into this gloomy picture. Indigenous people were guaranteed jobs, compensation for the use of their land and 2 percent equity in Asia Pacific Transport Consortium, the railroad’s parent company. For the first time, Aborigines are shareholders in a major national enterprise.

As the train left Alice Springs and began to climb the Great Larapinta Grade up to Bond Springs, at 2,390 feet the highest point on the line, the excitement onboard grew palpable: we were the first people to cross this part of Australia by train. My favorite perch was an open doorway between two carriages. The engineer had warned me that if the driver braked suddenly, I could be pitched onto the track. But I spent hours watching what the Australian novelist Tom Keneally called the “sublime desolation” of central Australia, as we thundered across a wilderness of rust-colored dirt, saltbush and spinifex grass stretching toward a horizon so flat, and so sharply defined, that it looked as if drawn with a pencil. I saw no sign of human

life: not a house, not a person, not a car, just some scrawny emus, which scampered into the bush at our approach.

The emptiness took on even more menace about three in the afternoon when our train broke down—and with it the air conditioning. (Our 50-year-old German-built car had come to Australia as part of World War II reparations.) As we sat in the carriage with sweat pouring down our faces, I remembered that explorer Charles Sturt’s thermometer had burst in 1845 during his journey across the desert. “The ground was so heated,” he wrote in his journal, “that our matches, falling on it, ignited.”

It was a searing reminder that building this railroad had required epic endurance, teamwork and hard yakka, as Australians call tough physical work. Six days a week, around the clock, a workforce of 1,400 labored in temperatures that sometimes reached 120 degrees Fahrenheit, laying nearly 900 miles of steel railway across the heart of Australia in just 30 months. There were no mountains to cross or giant rivers to ford—just deadly snakes, blowflies, monstrous saltwater crocodiles (at the Elizabeth River, a loaded rifle was kept close at hand in case workers who ventured into the water met up with a croc), and one of the most extreme climates in the world. Here it was the heat. And in the tropical upper half of the Northern Territory, known as the top end, there are only two seasons: the dry and the wet, as Australians call them. Between April and September there’s no rain at all, and during the next six months you need a diving suit to pick a tomato.

At their peak, the construction crews were laying more than two miles of track per day, and with every mile racist stereotypes of feckless Aborigines drunk on grog or simply disappearing from work, known derisively as “going walkabout,” were overturned. “There has never been a major project in Australia with this sort of indigenous participation,” says Sean Lange, who ran a training and employment program for the Northern Land Council (NLC), an aboriginal land management organization based in Darwin. The NLC had originally hoped that 50 Aborigines would work building the railway; more than three times that many found jobs. The railroad-tie factory in the town of Tennant Creek, where the workforce was about 40 percent aboriginal, was the most productive that Austrak, the company that ran it, had ever operated.

One aboriginal worker was Taryn Kruger, a single mother of two. “When I started at the training class in Katherine, there was only one white bloke,” she told me, a pair of welding goggles round her neck. “On the first day he looked round the classroom and said, ‘Hey, I’m the only white fella!’ So I leant over to him and said: ‘Hey, if it helps you, I’m the only girl!’ ”

Her first job on the railroad was as a “stringliner,” signaling the drivers of bulldozers and scrapers grading the track how much earth they had to remove. “I loved the rumble,” she said, referring to the sound made by the earthmoving vehicles. “When they went past, I would reach out and touch them. It was a rush.” Kruger eventually got to drive a piece of heavy machinery called a “cat roller,” which she pronounces with the same relish that others might use for “Lamborghini.” Now, she said, “sometimes I take my children up to Pine Creek. There’s a bit where you can see the railway from the road. And they say: ‘Mummy, you worked there!’ And I say: ‘That’s right, baby. And over here too. Look! You see that bit of track down there?

Mummy helped build that.’ ”

After the train had spent an hour sitting motionless in the outback’s infernal heat, a sweating Trevor Kenwall, the train’s mechanic, announced between gulps of water that he had fixed the problem.

At our next stop, Tennant Creek, some of the 1,000 or so people who greeted our arrival stared at the locomotive as if it had arrived from outer space. Squealing children waved balloons. A group of elderly women from the Warramunga tribe performed a dance, naked except for saffron-colored skirts and white cockatoo feathers in their hair.

As we headed north, the land seemed emptier and more mysterious. We were now entering the top end, where the wet season was in full deluge. With the water came wildlife: ducks, turkeys, hawks and nocturnal birds called nightjars rose up in a commotion of wings. Akangaroo appeared at the side of the track, mesmerized by the locomotive’s headlamp. My stomach tightened. Aconductor switched off the light to break the spell and give it a chance to escape, but moments later there was a loud bang, then a sickening sound.

Opening my cabin blinds at the start of our final day, I looked out on a wet, green world. Cockatoos zipped in and out of the trees. A wallaby found refuge under a palm tree. The humid air smelled of moist earth and vegetation. “Hallo train . . . welcome to Darwin!” a sign said as we pulled into the new Berrimah Yard freight terminal, the end of our journey across Australia. Darwin is Crocodile Dundee country, a hard-drinking, tropical city of 110,000 people where the average age is 32, men outnumber women by almost two to one, and the bars have names like The Ducks Nuts.

Before the Stuart Highway into Darwin was made into an all-weather road in the 1970s, the city was regularly cut off during the wet season. It used to be said that there were only two kinds of people in Darwin—those paid to be there and those without enough money to leave. Today, the city wants to be a player in Australia’s economy, and the transcontinental is a key part of that dream. “For the first time in our history, we’re connected by steel to the rest of Australia,” said Bob Collins, who as federal transport minister in the early 1990s was a passionate advocate of the project. “And that’s exciting.”

Collins, a white man who is married to an aboriginal woman, applauds what the train will do for indigenous people. Sean Lange says the coming of the railroad may spawn as many as 5,000 jobs. “There are 4 or 5 billion dollars’ worth of projects happening here in the Northern Territory over the next five years,” he says. “We’re determined that indigenous people are going to get some of those jobs.”

The railroad will also become part of the aboriginal story: a steel songline across the heart of their world. “It will be incorporated into aboriginal knowledge,” says anthropologist Andrew Allan. “Aboriginal people who have worked on the railroad will recall it, and tell stories about it. And they’ll tell their children. And so the railway will become part of the historical landscape.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.