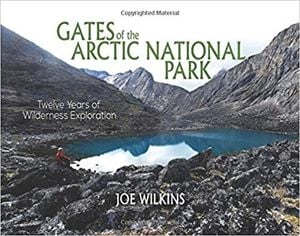

Photos Offer a Glimpse Into the Wild Corners of America’s Northernmost National Park

In his upcoming book, author Joe Wilkins gives an insider’s perspective of Gates of the Arctic

Life in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve isn’t for the weak. There are no roads leading to America’s northernmost and second largest national park and no designated trail system once inside. And if you’re hoping to see another human being during your journey, good luck, because with a total land area of 8.5 million acres, the only company you’ll likely have are the wolves and grizzly bears that inhabit this massive park. But that hasn’t stopped Joe Wilkins from returning year after to year to explore this rugged landscape deep within northern Alaska. Since 1966, Wilkins has made repeated trips into the wilds of Gates of the Arctic, navigating white-water rapids, coming face to face with grizzly bears and surviving off the land–often in complete solitude. Now, in his upcoming book, “Gates of the Arctic National Park: Twelve Years of Wilderness Exploration,” he takes a look back at some of his time in this harsh yet beautiful national park and offers advice for anyone who is brave enough to go there.

What initially drew you to Gates of the Arctic?

I first came to this area as a young military officer in 1966 to attend Arctic wilderness survival training, and then in the 1970s I would go hiking and backpacking around the Brooks Range. This area of Alaska is the northernmost national park and the second largest national park in the system. It’s also commonly known as a “black belt park,” meaning that when compared with other national parks, it’s the toughest of the tough. That’s what drew me—the challenge and the opportunity of visiting an area that’s really, in my opinion, the most magnificent national park in America.

In your book you describe Gates of the Arctic as the “wildest of the wild places.” Why?

Gates of the Arctic is about 8 million acres in size, which is only a little smaller than Switzerland, and it’s entirely wilderness. It’s rugged and remote, it contains these really rugged mountains, white-water rivers and wild animals, and the weather conditions there are challenging. For example, the temperature can drop 50 degrees in literally minutes with a shift in cloud cover or wind direction. When you go there, you have to be prepared for anything.

Is there one part of Gates of the Arctic that always draws you back?

There are six rivers that have been officially designated as "wild and scenic," and they provide an arterial network throughout the park. I’ve always been drawn to them, and over the years I spent a lot of time in canoes and packrafts crossing them. It’s a wonderful way to explore a fairly large area. In the 1930s, wilderness activist Bob Marshall coined the phrase “Gates of the Arctic” to describe the area where the North Fork of the Koyukuk River passes between the Boreal Mountain and Frigid Crags. There’s an inordinate amount of wildlife there, including grizzly bears, wolves and moose.

Can you describe what a typical day was like for you when you were staying in the park?

It varies by time of year, but during the summer months, when you have 24 hours of sunlight, I would start off my morning with coffee and breakfast. You wind up consuming a lot of food because you’re very active. I’d be hiking and backpacking, so I was constantly expending calories, so you eat a lot. One of the things that is kind of interesting in this environment is you can encounter a rainbow at midnight in the summer that’s both comforting and alien. It’s easy to get excited and carried away and lose track of time, especially when the sun is out all day, but you have to remember to pitch your tent, eat and sleep.

There are no roads to and within the park. How did you navigate such an expansive area without getting lost?

That’s one of the challenges for people visiting, since you have to figure out how to get in. [Editor’s note: most people access the park via seaplane.] I always carry a GPS and topographic maps; frankly, I never completely trust anything that runs on batteries. I depend on maps, which I laminate in plastic, since you’re going to get wet. I also carry a compass, but you have to remember there are many degrees of deviation on the compass, since you’re getting closer to the North Pole and the North Magnetic Pole. You’re risking your life with these things, so I always have two ways to navigate. After being out there many times, I know the area pretty well, and I’m familiar with what mountain that is in the distance or which river that is. When a person first starts going out there, it’s best to go with someone knowledgeable of the area.

What training prepare you for backcountry travel?

I had a lot of survival training specifically in this part of Alaska through Elmendorf Air Force Base, so I learned how to navigate in wilderness areas. The military is a magnificent place to start learning that. I also grew up in a fairly remote part of southern Illinois. My first job was on a small farm in what is now Shawnee National Forest where I had a trap line for muskrats, so I have literally spent most of my life being comfortable in the wilderness. The military helped enhanced my skills.

I understand that you’ve faced down a few grizzly bears during your time in the park. What was that like?

People need to be very aware of bears, and you need to learn skills for bear awareness and bear avoidance. You don’t want to get into close contact with them. Now having said that, it does happen. There are two types of charges from a grizzly bear: predatory, when it’s coming to kill, and defensive, when it’s establishing its territory. So you need to be trained and experienced in using bear spray. I also carry a 12-gauge shotgun. I’ve never had to fire either one of those, and, frankly, I would consider it my own failure if I ever got into a situation where I had to do that. That would be my fault, not the fault of the animal. There are no hard or fast rules, but it is possible for you to read the body language of the bear. Does the hair on the back of its neck stick up? Are its ears up or down? How is it holding its head? Is it clicking its teeth? Is it salivating? You can make a judgment of the intent of the bear by reading its body language. The only problem is you have to do that in the space of one or two heartbeats. So if you're new to this kind of wilderness, you’re probably not going to have that kind of experience. In my case during both of these charges, I determined it was a defensive charge, and I stood my ground, I spoke loudly to them and made sure they knew I was a person. In many cases out there they’ve never seen a human being before, so you’re new to them.

Often you would go days without seeing another human. How did you deal with the solitude?

It’s very likely that during your entire time out there you won’t encounter another human being. Encountering another person is the exception not the rule. For example, during a five-week trip I took with a friend down the Kobuk River, we never saw another human. This is an experience that can be so valuable. We’re all far too accustomed to tools and toys, like an iPhone or an iPad, but up there they don’t work. Getting away from the entangling bonds of modern civilization is a refreshing experience and allows you to submerge yourself in a beautiful and challenging experience.

In the years you traveled through Gates of the Arctic, have you noticed changes in the landscape?

There are several glaciers, and each year you see them retreating. You can also see deformities out on the tundra from the north slope of the Brooks Range to the Arctic Ocean. You can see places where the tundra is melting and holes have opened up. In my book, I have pictures of pingos, which are small hills formed by freezing and thawing. There’s much evidence of global warming up there.

What’s one piece of advice you have for someone visiting the park for the first time?

Self-sufficiency isn’t desirable—it’s mandatory. You’re out there in a very remote and pristine wilderness area, and you have to be prepared. You need to study and make preparations for your gear and food, and make sure that you have the appropriate kind of clothing for rain and snow. This park provides visitors with the ultimate wilderness experience in North America—it’s both delicate and dangerous and is vulnerable to damage—so you have to be careful to protect the environment out there. This area is where human history in North America began. The first people to inhabit it were descendants of the intrepid explorers who, thousands of years before, used a land bridge that connected Siberia to North America. For them this was not really wilderness, this was home. You can see remnants of their habitations throughout Gates of the Arctic. For example, you can see where people honed their tools and weapons and the chert flakes left behind. You can also see the inuksuk or vertical stone markers used by nomadic hunters to help guide caribou during migration. You almost have a literal handshake with the people across the millennia who lived there, since you can touch the stones they touched and the remnants of the tools they made. There’s just a tremendous amount of history here.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e1/01/e101d00e-ae10-4508-80ea-6f3244cfffab/6_developingperspective_jonkrakauer02.jpg)