The Genius of Venice

The seafaring republic borrowed from cultures far and wide but ultimately created a city that was perfectly unique

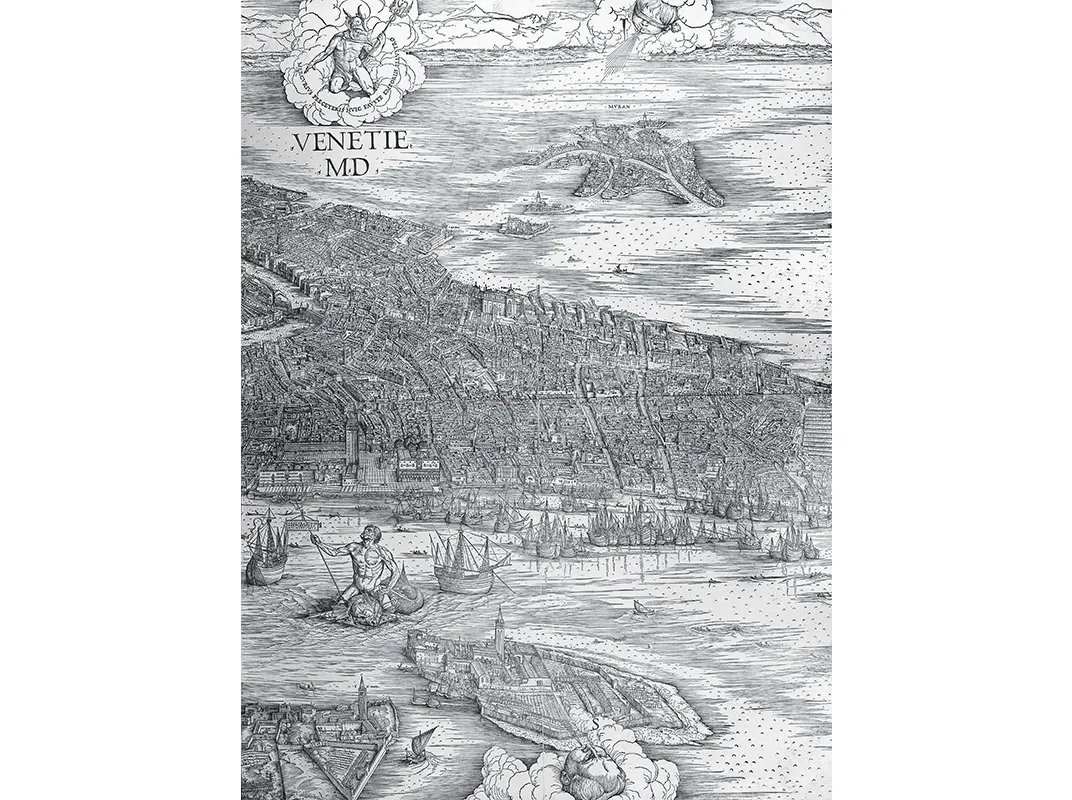

In the Correr Museum at the end of St. Mark’s Square, there’s a spectacular city map. It was produced in 1500 by Jacopo de’Barbari to celebrate the half millennium and the glory of Venice. At nearly three meters (ten feet) long, printed from six giant woodblocks on sheets of paper of unprecedented size, it was also an advertisement for Venice’s supremacy in the newfangled art of printing. The method behind its perspective was equally ingenious: Barbari had surveyed the city from the tops of bell towers to portray it in bird’s-eye view as if from a great height. Houses, churches, ships, the S-shaped meander of the Grand Canal—everything is laid out in magisterial detail, and the whole scene is watched over by Mercury and Neptune, the gods of commerce and the sea.

The Barbari map projects the image of a blessed place. Venice appears to be immortal, its greatness ordained in the classical past, its effortless wealth resting on a mastery of trade and navigation. This was very much how it struck visitors at the time. When the French ambassador, Philippe de Commynes, arrived in 1494, he was plainly astonished. To float down the Grand Canal past the grand palazzi of the merchant princes, such as the Ca’ d’Oro shimmering in its covering of gold leaf, was to be witness to an extraordinary drama of activity, color and light. “I saw 400-ton vessels pass close by the houses that border a canal, which I hold to be the most beautiful street,” he wrote. To attend Mass in St. Mark’s Basilica or observe one of the splendid ceremonies of the Venetian year—the marriage of the sea on Ascension Day, the inauguration of a doge or the appointment of an admiral, the parading of captured war trophies, the great processions around St. Mark’s Square—these theatrical displays seemed like manifestations of a state that was uniquely favored. “I have never seen a city so triumphant,” declared Commynes. Our modern reaction on sighting Venice for the first time is almost identical, no matter how many prior images we’ve been exposed to. We are also astonished.

Yet the story Venice told about itself, the story behind the map, was a creative invention, like the city itself. It claimed the preordained patronage of St. Mark, but it had no connection with early Christianity nor any link with the classical past. Venice was comparatively new. It was the only city in Italy not to have existed in Roman times. People probably fled into the Venetian lagoon to escape the chaos of the empire’s collapse. Its rise from a muddy marsh to a miraculously free republic of unequaled prosperity was not the gravity-defying marvel it appeared. It was the result of centuries of self-disciplined effort by a hardheaded, practical people.

The original genius of Venice lay in its physical construction. Painstakingly reclaiming marshland, stabilizing islands by sinking oak piles in the mud, draining basins and repairing canals, maintaining barriers against the threatening sea: All required ingenuity and high levels of group cooperation. The ever shifting lagoon not only shaped the city but also gave rise to a unique society and way of life. Beyond the fish and salt of the lagoon, Venice could produce nothing. Without land, there could be no feudal system, no knights and serfs, so there was a measure of equality. Without agriculture, seafaring and trade were its only options, so the Venetians had to be merchants and sailors. They were literally all in the same boat.

From the start, building and living on a marsh required original solutions. Houses raised on wooden pontoons had to be lightweight and flexible. The brick or stone facades of even the great palazzi are a thin skin, the bricks supporting the roofs are hollow, the floors constructed of an elastic mixture of mortar and shards of stone or marble. Equally challenging was the provision of drinking water. One of the many paradoxes of livingin this unpromising place was its absence. “Venice is in the water but has no water,” it used to be said. The ornate wellheads that you can find in almost any campo conceal a complex scheme for water collection. Beneath the square a substantial clay-lined cistern was constructed, connected to an immense network of pipes and gutters that fed rainwater off the roofs and hard surfaces, through a sand filtration system and into the well. By the early 14th century, a hundred thousand people depended on these wells; at Venice’s height, more than 200,000.

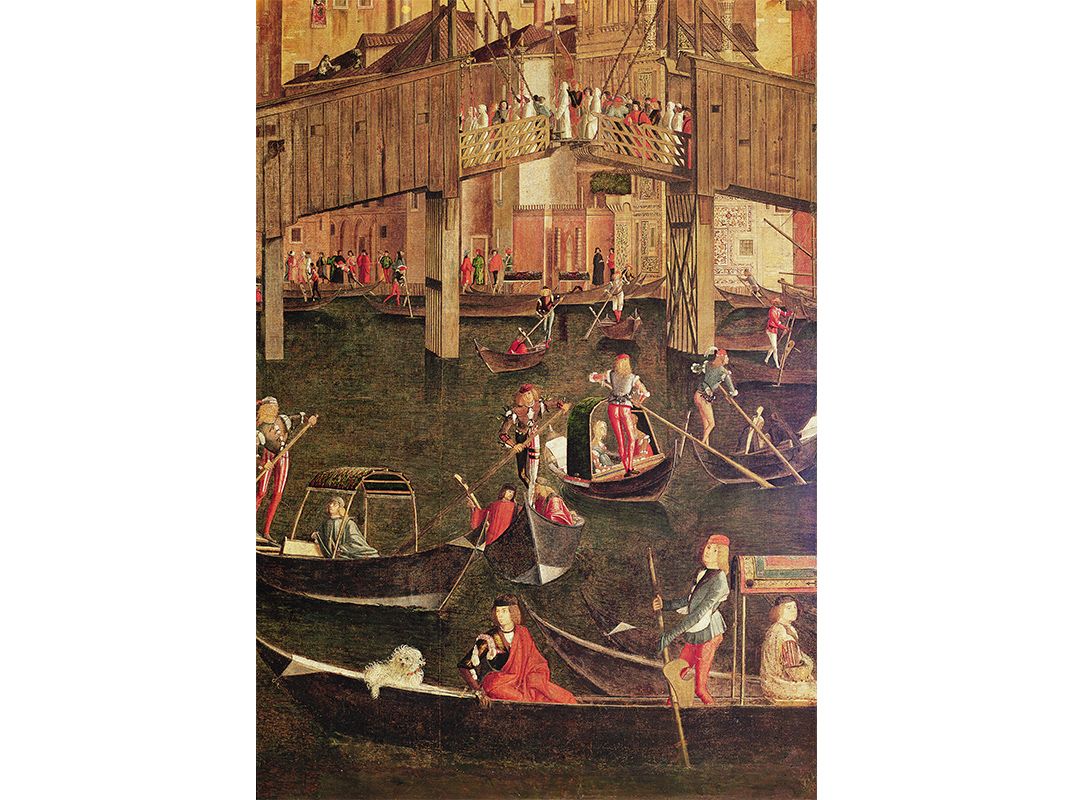

The ingenuity involved in building the city’s infrastructure may be hidden from view, but it’s as original as anything else the Venetians created. Even so, the wells were never sufficient. In the summer months, flotillas of boats plied back and forth bringing freshwater from the mainland. If we are startled now by the array of vessels shuttling about, the formerly absolute dependence on shipping has been reduced by the causeway that connects Venice to the rest of Italy. You have to look at Canaletto’s paintings to get any sense of Venice’s historical relationship with the sea. They depict a world of masts and spars, barrels and sails, ship repair yards and literally thousands of vessels, from tiny skiffs and gondolas to large sailing vessels and oared galleys. Embarkation was a central metaphor of the city’s life, frequently repeated in art. The walls of the Doges’ Palace, the very center of the state, are embellished with colossal paintings depicting the city’s maritime victories, maps of the oceans and allegorical representations of Neptune offering Venice the wealth of the sea.

**********

Sailing was Venice’s lifeblood. Everything that people bought, sold, built, ate, or made came in a ship: the fish and the salt, the marble, the weapons, the oak palings, the looted relics and the old gold; Barbari’s woodblocks and Titian’s paint; the ore to be forged into anchors and nails, the stone for palaces on the Grand Canal, the fruit, the wheat, the meat, the timber for oars and the hemp for rope. Ships brought people too: visiting merchants, pilgrims, tourists, emperors and popes. Because maritime supply was critical to survival, the Venetian Republic was obsessively attentive to detail and engineered revolutionary construction and management techniques.

The hub of all maritime activity was the state arsenal. To stand outside its magnificent front gate, embellished with an array of lions, is to behold one of the wonders of the Middle Ages. By 1500, the 60-acre site enclosed by high brick walls was the largest industrial complex in the world. Here the Venetians built and repaired everything necessary for maritime trade and war. Along with turning out merchant ships and war galleys, the arsenal produced ropes, sails, gunpowder, oars, weapons and cannons by methods that were hundreds of years ahead of their time. The Venetians analyzed every stage of the manufacturing process and broke it down into a prototype of assembly-line construction. Galleys were built in kit form by craftsmen who specialized in the individual components, so that in times of crisis ships could be put together at lightning speed. To impress the visiting French King Henry III in 1574, the arsenal workers assembled a complete galley during the length of a banquet.

Their concern for quality control was similarly cutting-edge. All work was subject to rigorous inspection; ropes were color tagged according to their intended use; every ship had a specified carrying capacity with a load line marked on its side, a forerunner of the Plimsoll mark. This care was a function of the city’s deep understanding of the demands of the sea. A vessel, its crew and thousands of ducats of valuable merchandise could founder on shoddy work. For all its visual splendor, Venice was a sober place. Its survival ultimately depended on practical materials—wood, iron, rope, sails, rudders and oars—and it made unconditional demands. Caulkers should be held accountable for split seams, carpenters for snapped masts. Poor work was punishable by dismissal.

**********

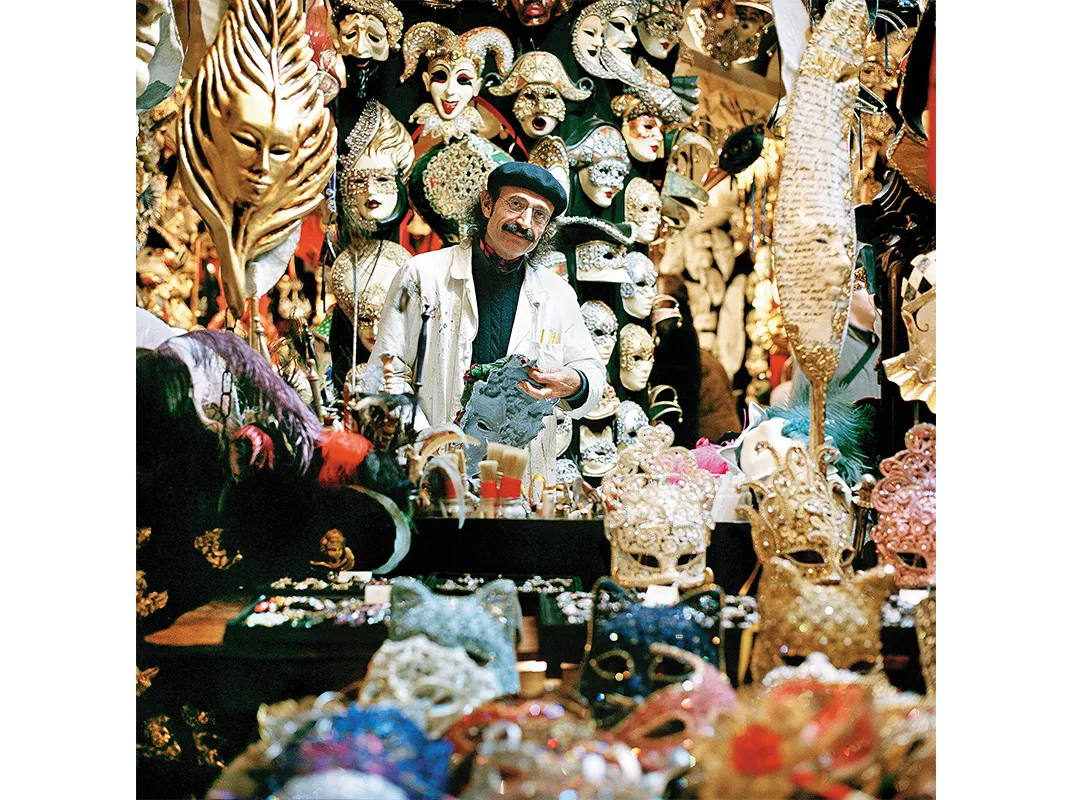

If Venice seems unique, it was the wide area of its maritime trade that allowed it to be so. This most original of cities is paradoxically a treasure trove of borrowings. Along with obtaining food and merchandise, the Venetians acquired from overseas architectural styles and consumer tastes, the relics of saints and industrial techniques. They spirited the bones of St. Mark away from Alexandria, hidden from the gaze of Muslim customs officials in a barrel of pork, and made him their protector. Out of such imported elements they conjured a city of fantasy, complete with its legends, saints and mythology. Gothic arches, orientalist domes and Byzantine mosaics carry reminders of other places—Bruges, Cairo, or Constantinople—but ultimately Venice is itself.

No place expresses this alchemy so strongly as St. Mark’s Basilica. It’s a rich assortment of artistic elements, many stolen during the notorious Fourth Crusade that set out to retake Jerusalem and ended up sacking and plundering Christian Constantinople. The building is modeled on that city’s great churches but embeds an assemblage of visual styles. The domes feel Islamic; the facade is studded with columns from Syria; there’s a quaint statue of four small Roman emperors on one corner; the horses (now only replicas) that once graced the Constantinople hippodrome paw the soft lagoon air as reinvented symbols of Venetian freedom.

The two pillars nearby that greet visitors at the waterfront are equally extraordinary concoctions. The columns are of granite from the Middle East, crowned with capitals in a Byzantine style. On the top of one is the figure of St. Theodore, fashioned from a classical Greek head joined to a slightly newer Roman torso, with his feet on a crocodile sculpted in Venice in the 14th century. On the adjacent column, the immense lion, weighing three tons, may be of ancient Middle Eastern or even Chinese origin. The wings were most likely added in Venice and an open Bible inserted between its paws to create that most potent symbol of Venetian power: the lion of St. Mark. The Venetian genius was to transform what its traders and merchants imported from far and wide into something expressly its own, with the purpose of advancing “honor and profit,” as city fathers liked to put it. The Venetians were particularly active in the theft or purchase of holy relics from across the eastern Mediterranean. These conferred respect on the city and attracted pious tourists. So plentiful was this collection that at times they forgot what they had. The American historian Kenneth Setton discovered “the head of St. George” in a church cupboard in 1971.

**********

Many of the innovations that revolutionized Venice’s trade and industry also had their origins elsewhere. Gold currency, marine charts, insurance contracts, the use of the stern rudder, public mechanical clocks, double-entry bookkeeping—all were in use in Genoa first. Printing came from Germany. The manufacture of soap, glass, silk and paper, and the production of sugar in Venetian Cyprus were learned from the Middle East. It was the use to which they were put that set Venice apart. In the case of silk manufacture, the city acquired raw silk and dyes through its unique trading links and encouraged the immigration of skilled workers from the mainland city of Lucca, which had an initial lead in the industry. From this base, it developed a novel trade in luxury silk fabrics that it exported back to the East—to the silk’s point of origin.

The city’s advantage was its access to these raw materials from across the world. Its genius was to master technical skills and exploit their economic potential. Glass manufacture on the island of Murano—still one of the most celebrated artisanal skills—is a supreme example. The know-how and ingredients were imported. Production began with window glass and everyday utensils; in time, through skillful innovation, the glassmakers developed a high-end business. Venice became famous for enameled and exotic colored ware and glass beads. The glassmakers revolutionized the mirror industry with the introduction of crystalline glass, and they produced eyeglasses (another outside invention) and fine chandeliers. State management and monopoly were the keys to industrial development. Glassmaking was tightly regulated and trade secrets jealously guarded. Its workers were forbidden to emigrate; those absconding risked having their right hands cut off or being hunted down and killed. Venetian glass came to dominate the European market for nearly two centuries and was exported all the way to China.

Even more dramatic was the development of printing. The city was not particularly noted as a center of learning, but it attracted skilled German printers and foreign capital. Within half a century of printing’s introduction into Europe, Venice had almost cornered the market. The city’s printers developed innovative presses and woodcut techniques. They published the classics, in Greek as well as Latin, with texts prepared by the scholars of the day; they saw the potential for printed sheet music and illustrated medical texts. And they improved reader experience: Aldus Manutius and his descendants invented punctuation and italic type, and they designed elegant typefaces. Sensing a desire for both fine editions and affordable reading, they anticipated the paperback by 500 years, quickly following up initial publication with cheaper pocketbook versions in innovative bindings. Print runs soared. By 1500, there were more than a hundred print shops in Venice; they produced a million books in two decades and put a rocket under the spread of Renaissance learning. All of Europe turned to Venice for books as it did for mirrors, woven silk, fine metalwork and spices.

**********

It was in the streets around the Rialto Bridge—now stone, once wood—that the fullest expression of Venice’s commercial skill could be appreciated. Today, the area is still a hubbub: the water alive with boats; the bridge thronged with people; the fish and vegetable markets a colorful swirl of activity. At its height it was astonishing.

Goods arriving at the customs house on the point opposite the Doges’ Palace were transshipped up the Grand Canal and unloaded here. The Rialto, situated at the midpoint of the canal, was the center of the whole commercial system. This meeting point became the axis and turntable of world trade. It was, as the diarist Marino Sanudo put it, “the richest place on Earth.”

The abundance dazzled and confounded. It seemed as if everything that the world might

contain was landed here, bought and sold, or repackaged and re-embarked for sale somewhere else. The Rialto, like a distorted reflection of Aleppo, Damascus, or medieval Baghdad, was the souk of the world. There were quays for unloading bulk items: oil, coal, wine, iron; warehouses for flour and timber; bales and barrels and sacks that seemed to contain everything—carpets, silk, ginger, frankincense, furs, fruit, cotton, pepper, glass, fish, flowers.

The water was jammed with barges and gondolas; the quays thronged by boatmen, merchants, porters, customs officials, thieves, pickpockets, prostitutes and pilgrims; the whole scene a spectacle of chaotic unloading, shouting, hefting and petty theft.

In the nearby square of San Giacomo, under the gaze of its enormous clock, the bankers conducted business in long ledgers. Unlike the bawl of the retail markets, everything was undertaken demurely in a low voice, without disputes or noise, as befitted the honor of Venice. In the loggia opposite, they had a painted map of the world, as if to confirm that all its goods might be concentrated here. The square was the center of international trade. To be banned from it was to be excluded from commercial life. Around lay the streets of specialist activities: marine insurance, goldsmithing, jewelry.

It was the sensuous exuberance of physical stuff, the evidence of plenty that overwhelmed visitors to the quarter. It hit them like a physical shock. “So many cloths of every make,” wrote one amazed onlooker, “so many warehouses full of spices, groceries, and drugs, and so much beautiful white wax! These things stupefy the beholder … Here wealth flows like water in a fountain.” It was as if, on top of everything else, the Venetians had invented consumer desire.

But perhaps the most radical invention of the Venetian spirit was the creation of a state and society focused entirely on economic goals. Its three centers of power, the Doges’ Palace, the Rialto and the arsenal—the seats of government, trade and shipping—were situated so close together they were almost within shouting distance. They worked in partnership. Outsiders were particularly impressed by the good order of St. Mark’s Republic. It seemed like the model of wise government—a system free from tyranny where people were bound together in a spirit of cooperation. They were led by a doge whom they elected through a complex voting system designed to prevent vote rigging, then shackled with restraints. He was forbidden to leave Venetian territory or to receive gifts more substantial than a pot of herbs. The aim was political stability for a common end: the pursuit of business.

**********

Trading was hardwired into the Venetian psyche. “We cannot live otherwise and know not how except by trade,” the city fathers wrote in a petition to a pope to lift a ban on trading with the Islamic world. Venetians hailed the man of business as a new kind of hero. Everyone traded: doges, artisans, women, servants, priests. Anyone with a little cash could lend it on a merchant venture. There was no merchant guild in the city. Everyone was a merchant and sold whatever people would buy and to whomsoever: Indian pepper to England and Flanders; Cotswold wool and Russian furs to the Mamluks of Cairo; Syrian cotton to the burghers of Germany; Chinese silk to the mistresses of Medici bankers and Cyprus sugar for their food; Murano glass for the mosque lamps of Aleppo; war materials to Islamic states. Merchants were frequently lambasted for their commercial ethics. There was even a trade in ground-up mummies from Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, sold as medicinal cures, and around 1420 the Venetians spotted a market in carrying pilgrims to the Holy Land and launched the first all-inclusive “package cruises.

The Venetians possessed a precocious grasp of economic laws. Following Genoa’s lead, they created a stable currency, the ducat, three and a half grams of pure gold. It became the dollar of its day, recognized and valued all the way to India, and retained its integrity for 500 years. They understood the need for rational taxation, disciplined and long-term policies and just-in-time delivery, ensuring their merchant convoys delivered goods on schedule for the great trade fairs that attracted buyers across Europe. And they lived with an unusually acute sense of time.

Venice’s public timepieces—the ornate clock tower in St. Mark’s Square, the merchant’s clock in San Giacomo’s—were both prestige statements and working tools. They set the pattern of the daily round; the ringing of the Marangona, the carpenter’s bell, from the campanile in St. Mark’s Square called the shipwrights to their tasks; auctions were conducted on the life of a candle. Time itself was a commodity. It could make the difference between profit and loss, riches and ruin. Venetian people counted carefully the dates for repaying debts, for the return of the spice fleets from Alexandria and Beirut, for trade fairs, festivals and religious processions.

The Venice of 1500 was almost the first virtual economy, an offshore bonded warehouse with no visible means of support. It rested on an abstract: money. The lion of St. Mark was its corporate logo. It’s all somehow shockingly modern. And yet, as visitors, we don’t perceive this. In quiet back alleys beside still canals, you can lose all sense of time; you feel you might slip between centuries and come out in some other age. And returning from the Lido on a vaporetto, Venice appears hazily in the distance, with the angel Gabriel gleaming golden from the summit of the campanile. It seems an unfeasible mirage. You have to rub your eyes and look twice.

Read more from the Venice Issue of the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1510_Venice_Contrib_03.jpg)