Goodbye My Coney Island?

A new development plan may alter the face of New York’s famous amusement park

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/coney_astroland.jpg)

It takes less than an hour and a subway fare of two dollars to get from midtown Manhattan to the southwestern edge of Brooklyn. There, crowds gather just off Surf Avenue, attracted by a barker with the handle of a screwdriver protruding from one nostril. Some turn their attention toward Serpentina, Insectavora or Diamond Donny V, who boasts "unnatural acts with animal traps." Slightly beyond the arcades, concession stands and haunted house rides, the wooden Cyclone rollercoaster clacks its way towards an 85-foot drop.

For more than a century, visitors to Coney Island have been able to ride the rides, swim in the ocean (year-round, for Polar Bear Club members) and explore Astroland Park, which stretches six blocks between Surf Avenue and the boardwalk. Within the past year, however, regulars may have noticed that go-karts, bumper boats, a miniature golf course and batting cages have gone missing. Their removal is the first step in the extinction of the three-acre Astroland. Last November, the land was sold to development company Thor Equities and will close for good in September 2007.

The change may signal the end of an era. In June, the New York Times reported that Thor plans to build a $1.5 billion year-round resort on the site of Astroland, to include an indoor water park, hotels, time shares, movie theaters and arcades, among other attractions. Some feel this could revitalize the area, but opponents fear Thor's plan will turn a charming—if somewhat run-down—neighborhood into a noisy, oceanfront shopping mall.

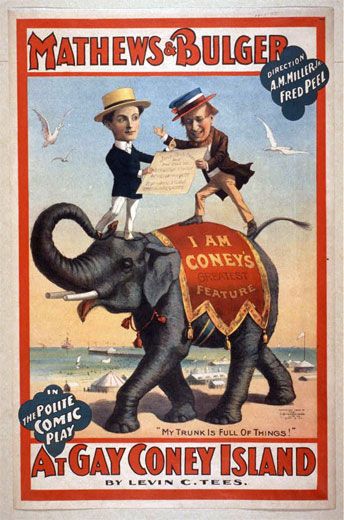

Whatever form it takes next, Coney Island has evolved greatly since the 1600s, when Dutch farmers are thought to have named the land for the rabbits—or konijn—inhabiting it. The site blossomed into a tourist destination after the Civil War when visitors could ride hand-carved carousels or stay in the Elephant Hotel, a building shaped like the animal, with a view of the ocean from the elephant's eyes and a cigar shop in one of its rear legs. Developers began changing the island into a peninsula in the early 20th century by filling in Coney Island Creek—a process that unfolded over several decades.

The period between 1904 and 1911 can be considered Coney Island's heyday, says Charles Denson, author of Wild Ride! A Coney Island Roller Coaster Family and head of the Coney Island History Project. As railroads allowed more city-dwellers to take daytrips to the beach, the area became "one of the most unusual places on Earth," he says, serving as a "testing ground for amusement park entrepreneurs." Together, the big three parks of the early 1900s—Steeplechase Park, Luna Park and Dreamland—gave Coney Island a reputation as the "People's Playground."

The attractions at these parks ranged from awesome to absurd. At Luna Park, gondoliers sailed through simulated Canals of Venice as elephants and camels wandered the grounds. At night, more than a million electric lights illuminated the park's towers and minarets. Dreamland's white, crisp attractions surrounded Coney Island's highest structure, the 375-foot-tall Beacon Tower. One Dreamland attraction, called Fighting the Flames, gave spectators the thrill of watching the simulated burning of a six-story tenement and subsequent rescue of its residents. Ironically, when this park also burned to the ground in 1911, it was the work not of Fighting the Flames but of light bulbs from a water ride.

Fires were a major problem at each park. (When Steeplechase burned in a 1907 blazer, founder George C. Tilyou promptly raised a sign offering: "Admission to the Burning Ruins—10 cents.") Gradually, as the number of car owners increased, people started turning down the subway trip to Coney Island in favor of a drive out to Long Island's beaches. By the mid-1960s, all three parks had closed.

When Dewey and Albert Jerome founded Astroland Amusement Park in 1962, they took over Coney Island's ailing amusement industry. They did not charge admission to their park, allowing visitors to wander freely among the rides and stands. The park remains best-known for the Cyclone, the wooden-tracked roller coaster built in 1927, which celebrated its 80th birthday in June. The famous ride, which lasts less than two minutes, has spawned clone Cyclones as far away as Japan. It has been named a New York City Landmark and part of the National Register of Historic Places, and it is one of the few rides that will remain intact after the property transfer.

Today, Coney Island offers more than just the beach and Astroland. The Brooklyn Cyclones play baseball at Keyspan Park from June through September. Professional eaters compete at a crowd favorite, Nathan's Famous International July Fourth Hot Dog Eating Contest; this year's winner, Joey "Jaws" Chestnut, ate 66 hotdogs (buns included) in 12 minutes. Free fireworks explode from the boardwalk every Friday night from late June through Labor Day. And this year marked the 25th anniversary of what has been called "the Mardi Gras of the North," the annual Mermaid Parade, a tradition inspired by the parades that took place in Coney Island for the first half of the 1900s.

Denson attributes Coney Island's uniqueness to the way it allows people of all means to mix. "It's still the People's Playground," he says. As for the fate of the neighborhood, that's still undecided. As Denson says, "Coney Island is always evolving."

Marina Koestler is a writer in Silver Spring, Maryland.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.