Halloween Is Spooky. But So Are These Eight Other Celebrations Around the World

From Setsubun in Japan to Fèt Gede in Haiti, these festivals relish in the macabre

:focal(512x327:513x328)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8e/18/8e184a3e-9614-4f16-b115-bbb54d314910/gettyimages-1961123428.jpg)

For millions of people around the world, especially in the United States and Europe, Halloween is one of the most enjoyable and atmospheric times of the year. People of all ages dress up in scary costumes, carve jack-o’-lanterns, go trick-or-treating, and regale each other with spooky stories. With roots stretching back to the ancient Pagan festival of Samhain (pronounced SAH-win), when the barrier between the worlds of the living and dead was believed to be at its thinnest, Halloween—with its ghosts, ghouls, witches and werewolves—has captured our imaginations for centuries.

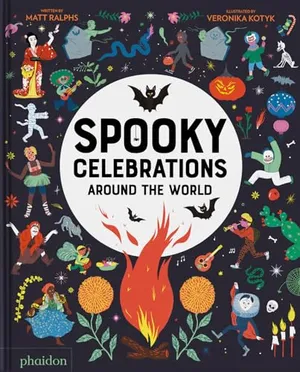

But Halloween is only one of many festivals around the world that focus, in one way or another, on the darker aspects of life. What struck me most while researching and writing my new children’s book on the subject, Spooky Celebrations Around the World, was not so much the differences between them (and they truly are a fascinatingly diverse collection of celebrations!), but the similarities: remembering and respecting the dead, family gatherings, traditional food and drink, incredible costumes, music, dancing, and telling stories. And in a world that often feels riven by bitter disagreement, these shared experiences can bring us closer together.

Spooky Celebrations Around the World

You’ll have heard of Halloween, and maybe Día de Muertos, or Obon too, but did you know there are spooky festivals all over the world?

Here are eight festivals that don’t fall short on fright.

Setsubun (Japan)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cb/3b/cb3b3b94-58e0-44f0-b912-3f3280fe86b1/gettyimages-1461643066.jpg)

Setsubun, which means “seasonal division,” is a centuries-old annual Japanese festival to welcome spring and drive out evil demons. Roasted soybeans called fukumame (meaning “fortune beans”) are thrown around the house to cries of “Oni wa soto! Fuka wa uchi!” (“Demons out! Happiness in!”). To add to the fun, adult family members and sometimes even schoolteachers don fearsome demon masks and pretend to terrorize the neighborhood. It’s up to the children to chase and pelt them with magic beans!

Like so many festivals (not just spooky ones), food plays an important part in Setsubun. It’s traditional to eat a sushi roll called ehomaki (“lucky direction roll”). Made from seven ingredients (the number 7 is lucky in Japan), ehomaki is eaten in silence while facing the direction that is considered luckiest; this direction changes annually. It’s also customary to eat the same number of beans as your age to ensure a year of good health.

Día de los Muertos (Mexico)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/66/ad/66ad27a9-66d5-4e7a-96fb-874a063e230b/gettyimages-1760556155.jpg)

It’s November 1 and the villages, towns and cities of Mexico are alive with the dead! On Día de los Muertos—Day of the Dead—the veil between the world of the living and the dead becomes thin, allowing the souls of the departed to return and reunite with their families. This is a happy time, a holiday filled with music, color, food and drink. Día de los Muertos originated in ancient Mesoamerica (now Mexico and Central America), where it was celebrated around July. But after the Aztecs were conquered by the Spanish in the 1520s, the date was moved to November to coincide with the Christian holiday of All Saints’ Day.

Alongside decorated floats, people in elaborate costumes, macabre masks and faces painted as skulls parade down the streets, all strung up with multicolored paper flags called papel picado. Families set up tables decked out with pictures of their departed loved ones. Ofrendas (“offerings”) of water, fruit, sugar skulls and sweet bread are also placed as gifts for their visiting spirits to enjoy. The atmosphere is one of fun and frivolity, because Día de los Muertos is a celebration of life and a vibrant demonstration that death is nothing to be afraid of.

Correfoc (Catalonia)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/33/f0/33f0c7ea-787f-4d11-a51d-bcad0811b031/gettyimages-1088159612.jpg)

Celebrated in Catalonia throughout the year on Catholic saint days, Correfoc is one of the noisiest, brightest and most exciting spooky festivals in the world. It’s also a little bit dangerous! It begins after dark. People gather expectantly on the streets or gaze from their windows, and then the performers arrive, all garbed in red devil costumes, complete with horns and pitchforks covered in sparkling fireworks. Drummers beat time, firecrackers burst and fizz, and demons cavort and dance.

It’s believed these riotous revelries date back to a type of medieval Catalonian street theater called ball de diables (“devils’ dance”). These religious performances included angels as well as devils, and represented the eternal battle between good and evil. Nowadays, the emphasis is on fun and, because spectators can get close to the performers in order to run with the fire, an element of risk, too. The dragons are perhaps the most dramatic part of Correfoc. Controlled by people inside them, these huge costumes are covered with fireworks to make them look like real beasts spitting out fire and brimstone.

Awuru Odo (Nigeria)

In some eerie festivals, the dead who return from the other side are to be feared, avoided or appeased to stop them from doing harm to the living. But this is not the case during Awuru Odo. This festival is celebrated by the Igbo people (pronounced EE-boh), most of whom live in Nigeria. The Igbo believe that those who have died remain as protective spirits who guide the living along their way. And for several months every two years, they return from the afterlife to live with their families again.

This happy visitation occurs between September and November. To represent the spirits’ return, men dress in masks and plant-fiber costumes and dance through the streets accompanied by drums and xylophones. Once the spirits have settled into their family homes to live and share meals as honored guests, more living relatives travel from far and wide to bring gifts and pay their respects. But bitterness must balance the sweet, and soon enough it’s time for the spirits to depart again. They do so accompanied by the prayers and good wishes of their hosts, and the masked-and-costumed men re-enacting their departure. Until the next time ...

Basler Fasnacht (Switzerland)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/2c/4a/2c4adab3-11dc-48df-b4d2-a8fdc6fd6b67/gettyimages-513178948.jpg)

For 72 hours during the festival of Basler Fasnacht, the Swiss city of Basel is transformed. Music, merriment, light and color fill the streets. All work stops, and bars and restaurants stay open all night. It begins at 4 a.m. on the Monday following Ash Wednesday. Crowds gather, excitedly waiting for the revelry to start. First, all the lights—even streetlamps—are turned off; from then on, illumination is cast by a sea of painted lanterns placed all over the city, some over 13 feet high. Then, through the multicolored lights, hundreds of musicians and masked performers march and carry colorful banners.

Basler Fasnacht is thought to be based on an ancient Celtic ritual performed to welcome summer. During the middle ages it became associated with knightly jousts, and then military musters—which could explain the emphasis on uniforms and marching bands. These days, costumes range from fairy-tale characters, clowns and harlequins to Napoleonic soldiers and celebrities. The three days of Basler Fasnacht are filled with more parades, concerts and performers riding on floats tossing sweets, confetti and flowers to the crowd. Tuesday is Kinderfasnacht—a special day for children when they can dress up and parade down the streets playing drums and pipes.

Gai Jatra (Nepal)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bb/53/bb536bc5-ed91-465c-af8d-954391935148/gettyimages-2166953599.jpg)

The Nepalese festival of Gai Jatra (usually occurring around August and September) is a joyful celebration, but it is rooted in tragedy. In the 17nth century, the son of King Pratap Malla was killed by an elephant. Desperate to comfort his grieving wife, Pratap Malla asked anyone in his kingdom who had lost a family member to dress up and perform a lighthearted parade for her. Upon seeing her subjects laugh and joke in spite of their sadness, the queen drew enough strength to find some cheer in her heart. And so, the Gai Jatra festival was born and has been celebrated ever since.

The tone of Gai Jatra is one of levity and laughter, and events include colorful parades traveling from holy place to holy place, music, dancing and comedy routines. As was Pratap Malla’s intention all those years ago, the aim is to provide some comfort to those who are grieving. The main religion in Nepal is Hinduism, and Hindus believe that cows are sacred. During Gai Jatra, families who have lost a loved one in the past year lead a cow in the procession, because cows guide the souls of the dead into heaven. And if a family doesn’t own a cow, they can dress a child as one and have them take part instead.

Matariki (Aotearoa New Zealand)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cb/9a/cb9af525-7ee9-47a9-90db-05d1ed029d8a/gettyimages-805162168.jpg)

To the Indigenous Māori people of Aotearoa New Zealand, the appearance of the beautiful star cluster Matariki (or Pleiades) on the horizon heralds a time called te mātahi o te tau: the new year. This usually occurs in the summer, and when it does, families gather to play music, tell stories and think about what is most important: remembering loved ones who have died, giving thanks to the good things they have in the present, and making plans for a prosperous, happy future. They also relate traditional Māori stories of how Matariki formed in the night sky.

One story features Tāwhirimātea, the god of weather. When Tāwhirimātea discovered that his parents, Ranginui the Sky Father and Papatūānuku the Earth Mother, had separated, he tore out his eyes in rage and threw them into the sky—where they became the shining Matariki star cluster. The word Matariki is a shortened version of Ngā mata o te ariki Tāwhirimātea, which means “the eyes of the god Tāwhirimātea.” The Māori believe that the unpredictability of the winds is caused by Tāwhirimātea’s self-inflicted blindness.

Fèt Gede (Haiti)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c7/95/c795a9dd-79d1-4660-bb20-fc69948ead26/gettyimages-1244404296.jpg)

Fèt Gede is celebrated by followers of the Voodoo religion on the Caribbean island of Haiti. Like many spooky festivals, Fèt Gede (which begins on November 1 and can last all month) is a time to remember the dead. But this is far from a sad occasion; rather, it is more of a joyful celebration of the lives lived by those who have passed. Revelers gather to dance, play music and take part in vibrant parades. Processions usually end at cemeteries, where people place food (including fried plantains, grilled sweet corn and sweet cakes), drink (rum and coffee) and lit candles on graves.

Adherents to the Voodoo religion believe in spirits called Iwa, who can be asked for help or protection in troubled times. Of the many different Iwa, a group called Gede is most closely associated with death and Fèt Gede (Fèt Gede means “Festival of the Dead”). The spirit Papa Gede is believed to be the first person who ever died. It is he who guides the souls of the dead to the afterlife and looks after the people of Haiti. In return, they honor him during Fèt Gede by dressing in his favorite colors of purple, black and white, and donning top hats.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.