This Austrian Ossuary Holds Hundreds of Elaborately Hand-Painted Skulls

Step inside Europe’s largest intact collection of painted remains

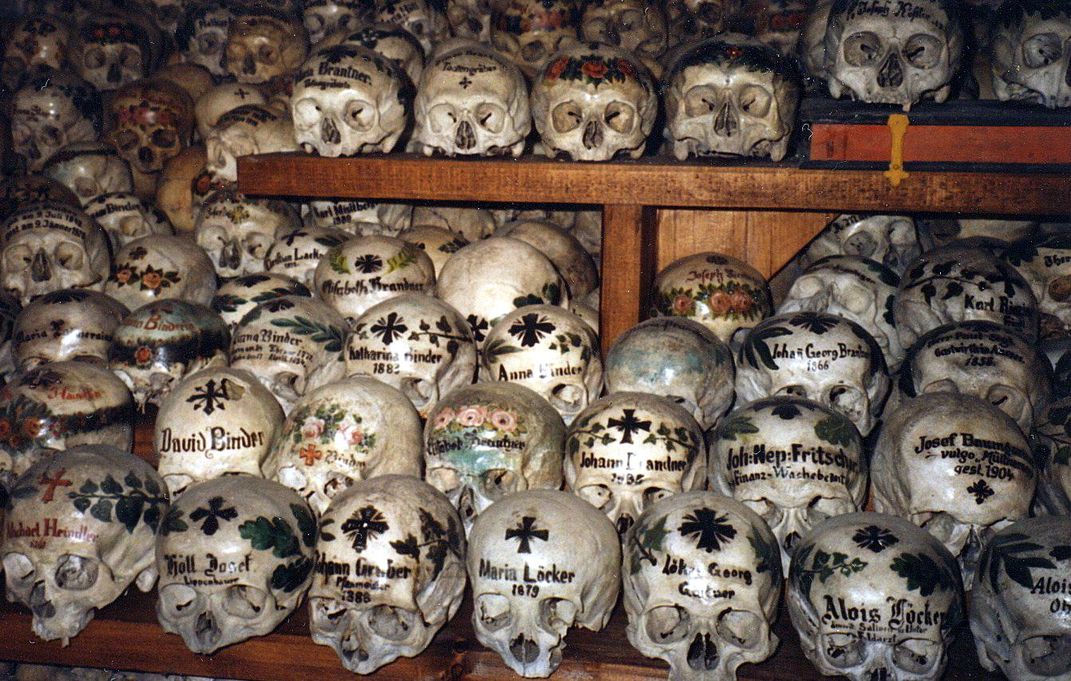

Nestled into the hillside of a small Austrian mountain town, the Hallstatt graveyard offers resting souls a spectacular view. Overlooking the Alps and a deep blue alpine lake, a few hundred gabled wooden grave markers stand in neatly clustered and carefully tended rows. But the modest collection of headstones grossly undercounts the number of permanent residents resting there. Only a few steps away, in the subterranean charnel house, more than a thousand skulls stand neatly stacked. 610 of these have been delicately hand painted, the largest intact collection of painted skulls anywhere in Europe.

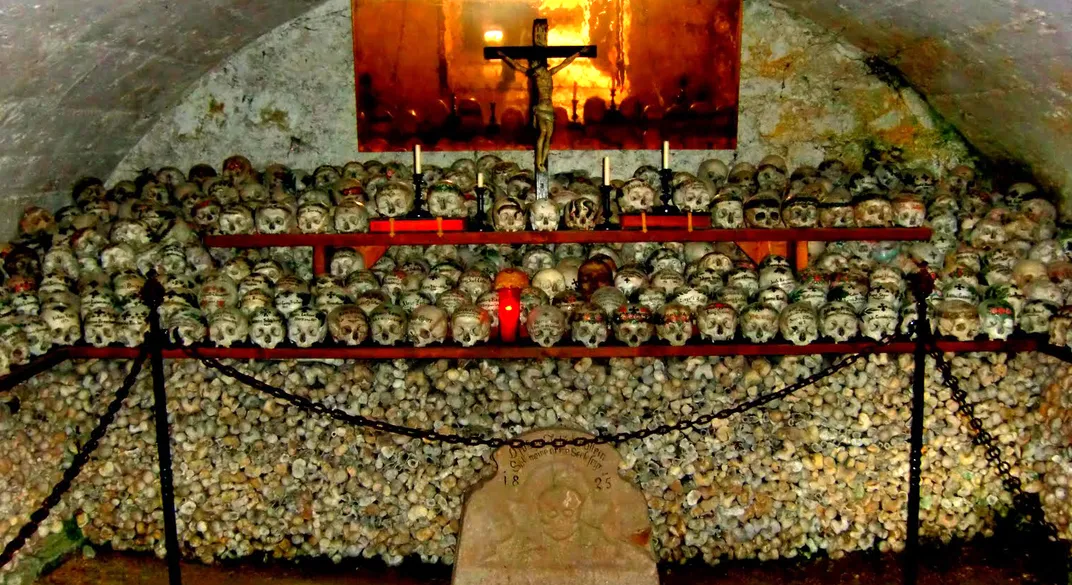

The rows of viewable bones are a result of the graveyard’s stunning geography. Bounded by mountains and water, by the 12th century the graveyard was full with no room to expand. According to Church practice, Catholics needed to be buried in sanctified ground, so the solution, employed by similar churchyards across Europe, was simply to reuse the graves. After about 15 years, the burial sites were reopened, cleaned out and given to new residents. The skulls and bones from the original buried bodies were moved to the lowest level of St. Michael’s Chapel, where they could be stored more efficiently.

Similar charnel houses were created in Catholic cemeteries all across Europe. At first the bones were just kept stacked in storage. But as the collections began to grow, many churches began to put the bones on display, creating viewing windows or walkable rooms to emphasize religious teachings.

"The point was to create a memento mori, a reminder of the inevitably of death, how it levels us all in the end." Paul Koudounaris, author of The Empire of Death: A Cultural History of Ossuaries and Charnel Houses, explained to Smithsonian.com. “When you look at the bone pile and see that one skull is the same as the other and you can't differentiate rich from poor, noble from beggar, [the church hoped] you [would] realize that worldly goods and honors are temporal and ultimately pointless in the face of eternity [and that you would]… concentrate on spirituality and salvation, [since] that's what's eternal and important."

"[But] over time… when the modern concept of individuality began to be born, that generic message was causing people more anxiety than comfort," Koudounaris continued. "They started to not like the idea of the equality of death. By especially the nineteenth century, which is the highpoint of the skull painting, they specifically wanted to be able to pick their ancestors out of the bone pile, be able to honor them individually even in the ossuary and remember their honors and status. Painting the skulls [which occurred mostly in the mountainous regions of Austria, Switzerland and Germany] was one way to do this. It was really a regional manifestation of a larger social concern that was going on in various places."

The tradition followed a specific process. First, the skull was removed from the grave and left to sit outside for a few weeks until all signs of decay were gone and the bones was bleached a delicate ivory by the sun. Then, the family, an artist or the undertaker collected the bones and began to paint, traditionally using shades of green and red. The majority were painted with flowers, often with floral wreaths featuring ivy, laurel, oak leaves or roses. Every part of the painting symbolized something: oak to signify glory; laurel, victory; ivy, life; and roses, love. Many also painted crosses and Latin text showing the name and life dates of the deceased. Once painted, the skulls were set on a shelf in the charnel house with the rest of the bones organized beneath. Families would often arrange the bones nearby the closest relatives.

The oldest painted skull in Hallstatt dates back to about 1720, though some unpainted ones may be older. As for the newest, that’s from 1995—long after Hallstatt stopped being used for new bones in the 1960s. It was then that the Catholic Church opted to allow cremation, nearly bringing to a stop the problem of overcrowded cemeteries. This most recent skull is a woman’s, with gold tooth intact; she died in 1983, and it’s said that her one wish in death was to be placed in the charnel house. New skulls may still be accepted by similar request.

***

Two more ossuaries of this type exist in Austria, both outside the skull-painting Alps region: the St. Florian Ossuary holding the skulls of 6,000, and the Eggenburg Charnel that artfully displays the remains of 5,800. But arguably neither of these compares to the lovingly painted and delicately stacked skulls in Hallstatt.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)