Hemingway’s Cuba, Cuba’s Hemingway

His last personal secretary returns to Havana and discovers that the novelist’s mythic presence looms larger than ever

A norther was raging over havana, bending and twisting the royal palm fronds against a threatening gray sky. My taxi splashed through the puddles along the Malecón, the majestic coastal road that circles half the city, as fierce waves cascaded over the sea wall and sprayed the footpath and street. Nine miles outside the city I arrived at what I had come to see: Finca Vigía, or Lookout Farm, where Ernest Hemingway had made his home from 1939 to 1960, and where he had written seven books, including The Old Man and the Sea, A Moveable Feast and Islands in the Stream.

The Finca Vigía had been my home too. I lived there for six months in 1960 as Hemingway's secretary, having met him on a sojourn to Spain the previous year, and I returned to the finca for five weeks in 1961 as a companion to his widow, Mary. (Later, I married Ernest's youngest son, Gregory; we had three children before we divorced in 1987; he died in 2001.) I well remember the night in 1960 when Philip Bonsall, the U.S. ambassador to Cuba and a frequent visitor, dropped by to say that Washington was planning to cut off relations with Fidel Castro's fledgling government, and that American officials thought it would be best if Hemingway demonstrated his patriotism by giving up his beloved tropical home. He resisted the suggestion, fiercely.

As things turned out, the Hemingways left Cuba that summer so Ernest could tend to some writerly business in Spain and the United States; his suicide, in Idaho on July 2, 1961, made the question of his residency moot. Shortly thereafter, Mary and I returned to Cuba to pack up a mass of letters, manuscripts, books and paintings and ship them to the United States, and she donated the finca to the Cuban people. I visited Cuba briefly in 1999 to celebrate the centennial of Ernest's birth and found his home, by then a museum, essentially as Mary and I had left it almost 40 years before. But recently I heard that the Cuban government had spent a million dollars to restore the villa to its original condition and that work on the grounds, garage and the author's fishing boat was in progress. I was curious to see the results.

Havana, ever a city of contrasts, was showing her age when I visited last spring, yet signs of renewal were faintly evident in the old city, La Habana Vieja, and in the once-fashionable Vedado section. The City Historian's Office has plowed some of the profits from Havana's hotels, bars and restaurants into the restoration of historic buildings.

Surprisingly absent from radio, television and even the lips of the people I talked to was the name of Fidel Castro, who was still recovering from his intestinal surgery of July 2006. But Ernest Hemingway, dead 46 years, was almost as palpable a presence as he was during the two decades he lived and wrote at Finca Vigía. Between these two towering figures of the late 1950s, who met only once and briefly (when Castro won a Hemingway-sponsored fishing tournament in May 1960), Havana seemed to be caught in a time warp, locked into that fevered period of Hemingway's physical decline and Castro's meteoric rise to power.

Except now it was Hemingway who was ascendant, more celebrated than ever. Festivities were in the works not only for the 45th anniversary of the Museo Ernest Hemingway's opening, this past July, but even for the 80th anniversary, next April, of Hemingway's first footfall in Cuba (when the author and his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, spent a brief layover in Havana on an ocean liner sailing from Paris to Key West in 1928).

The Hemingway I encountered on my ten-day visit was both more benign and more Cuban than the one I knew, with an accent on his fondness for the island and his kindness to its people. There seemed almost a proprietary interest in him, as if, with the yawning rift between the United States and Cuba, the appropriation of the American author gave his adopted country both solace and a sense of one-upmanship.

The director of the Museo Ernest Hemingway, Ada Rosa Alfonso Rosales, was waiting for me in her office, which had once been Finca Vigía's two-car garage. Surrounded by a staff of about half a dozen, a team of especialistas with pencils poised, tape recorder and video camera rolling, I fielded a barrage of questions about the finca and its former owners. Did I remember the color of the walls? Which important people had I met in the spring and summer of 1960? Those notations on Ernest's bathroom wall—could I identify who wrote the ones that aren't in his handwriting? After a while, I began to wonder whether it was my memory or my imagination that was filling in the gaps.

As we walked over to the main house after the interview, tourist buses were pulling into the parking lot. The visitors, about 80 percent of them foreigners, peered through the house's windows and French doors—their only option, since a special permit is needed to enter the premises. (Even so, I was told this is the most popular museum in Cuba.)

Inside, I felt distracted, not by the objects I was trying to identify, for I had taken little notice of them when I lived there, but by my memories. My Finca Vigía is not a museum but a home. Looking at the chintz-covered chair in the living room, I saw Hemingway's ample figure as he sat holding a glass of scotch in one hand, his head slightly nodding to a George Gershwin tune coming from the record player. In the dining room, I saw not the heavy oblong wooden table with its sampling of china place settings, but a spread of food and wine and a meal in progress, with conversation and laughter and Ernest and Mary occasionally calling each other "kitten" and "lamb." In the pantry, where the seven servants ate and relaxed, I recalled watching Friday-night boxing broadcasts from Madison Square Garden. For these matches, every household member was invited, and Ernest presided, setting the odds, monitoring the kitty, giving blow-by-blow accounts of the action.

Today, as in the past, old magazines were strewn on the bed in the large room at the south end of the house, where Ernest worked every morning, standing at a typewriter or writing in longhand, using a bookshelf as his desk. In the library next door each weekday afternoon, I transcribed as Ernest dictated answers to his business and personal letters. (He told me to take care of the fan mail as I pleased.) He would tell me about what he had written that morning or, on days of lesser inspiration, curtly report nothing more than a word count. The early months of 1960 were lighthearted and hopeful, but as spring turned to summer he became increasingly depressed by Cuba's political situation, his failing health and his growing inability to work.

Now, the house, which was once so well worn and lived in—even a bit shabby in places—seemed crisp and pristine and crystallized in time.

I had a similar thought when my hosts at the finca introduced me to three men from the surrounding village of San Francisco de Paula: Oscar Blas Fernández, Alberto "Fico" Ramos and Humberto Hernández. They are among the last living witnesses to Hemingway's Cuban life, and their recollections of the finca reached far back in time. Before Hemingway arrived in 1939, they told me, they and their friends used to play baseball in the street outside the house's gate. They used a flat piece of wood for a bat and a rolled-up wad of cloth for a ball. But after he bought the house, Hemingway was looking for playmates for his sons Patrick and Gregory (they were 11 and 8 at the time) during their summer visits. The new owner invited about a dozen Cuban boys, all 8 or 9 themselves, to bring the game onto the finca's grounds. He bought bats, balls, caps; he had a local seamstress make uniforms from discarded sugar sacks. Because Gregory (or "Gigi," pronounced with hard g's) was a star athlete, the team became known as Las Estrellas de Gigi, or the Gigi Stars. They played every summer through 1943.

Hemingway did the pitching—for both teams. At first the boys called him "mister"—"Not señor, mister," Blas recalled. But Gigi called him "Papa," and eventually the rest of the team followed suit. To this day, the surviving players, like much of the literary world, refer to him as "Papa Hemingway."

Some of the boys were given chores—picking up the mail, tending the many cats and dogs—so they could earn a little pocket money, and two of them worked at the finca after they completed their education. Mary taught Fico to cook, and he helped her make a Chinese luncheon for Ernest's 50th birthday, in 1949. His teammate René Villarreal became a houseboy at age 17 and butler soon afterward; Mary called him her hijo Cubano—her Cuban son. No one at the finca mentioned that she later helped him leave Cuba for New Jersey.

My tour of the finca complete, I returned to Havana, where I found the Cuban Hemingway again on display, at the Ambos Mundos Hotel, a dignified establishment from the 1920s that now caters primarily to upscale foreign visitors. The hotel has designated Room 511, where Hemingway stayed off and on in the 1930s, as a museum. The entrance fee is $2 CUC (Cuban Convertible Peso, on par with the U.S. dollar)—the precise amount Hemingway used to pay for a one-night stay. Framed black-and-white photographs of the man adorn adjacent walls behind a square mahogany tourism desk in the high-ceilinged lobby. At the hotel's rooftop restaurant, the menu lists a Hemingway Special, an elaborate fish dish with rice and vegetables, for about $15.

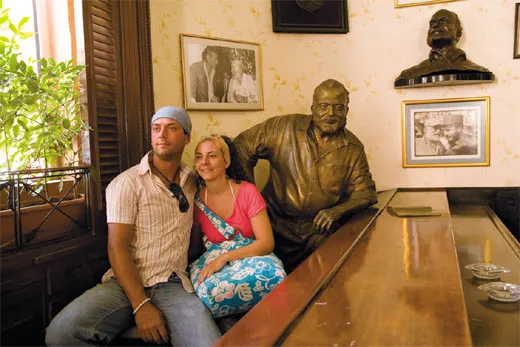

From the Ambos Mundos, I walked nine blocks to the Floridita bar, once a gathering place for American businessmen and Navy personnel, now famous as the cradle of the daiquiri and even more famous as Hemingway's favorite watering hole. Decorated in red velvet and dark wood, the place was throbbing with live music and thronged with European and South American tourists. Many lined up to have their photos taken beside a bronze Hemingway statue. The bartender set a dozen glasses at a time on the bar and expertly filled each with a daiquiri, the rum-and-lime-juice cocktail Hemingway described as having "no taste of alcohol and felt, as you drank them, the way downhill glacier skiing feels running through powder snow." On this occasion, I abstained and moved on.

Cojimar, the little port town six miles east of Havana where Hemingway kept his fishing boat, the Pilar, was the inspiration for the village he depicted in The Old Man and the Sea. It was once a busy fishing hub, but now the waters are mostly fished out. Gone, too, is Gregorio Fuentes, the Pilar's mate and the town's main attraction (he promoted himself as the model for Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, and indeed some scholars say he fit the bill); he died in 2002 at age 104. But, La Terraza, the restaurant and bar where Hemingway often stopped for a sundowner after a day of fishing for marlin or sailfish on the Gulf Stream, is still in business. Once a fisherman's haunt, today it is more heavily patronized by tourists. A few paces away, overlooking the water, is a bust of Hemingway, a tribute from local fishermen who, in 1962, donated metal for it from their boats—propellers, cleats and the like. When I was there, four professors from the University of Georgia at Athens were taking snapshots of the bust while their graduate students drank La Terraza's beer. Though the U.S. government bars American citizens from traveling to Cuba, it makes some exceptions, such as for education. The Georgia students, one of their professors said, were on a joint economic planning project with the University of Havana.

"For more than 30 years Hemingway had permanent contact with Cuba—in other words, for two-thirds of his creative life," the noted Cuban writer Enrique Cirules told me in the lobby of the Hotel Victoria, a writers' hangout where he had suggested we meet. "Yet students of his work and life concentrate solely on the European and U.S. years, and the influence of those places on his work. Cuba is never mentioned. I believe it is necessary to delve more deeply into the relationship between Hemingway and his Cuban environment."

Cirules is a handsome man of 68, slender and genial, a novelist, essayist and Hemingway scholar and enthusiast. He was not only reiterating what I had heard elsewhere in Cuba, he intends to personally rectify this perceived imbalance, having spent 20 years studying Hemingway's Cuban presence. His preliminary research was published in 1999 as Ernest Hemingway in the Romano Archipelago, a work through which the mythic Cuban Hemingway strides.

"It is as though he still roamed the streets of Havana, with his corpulence, his broad shoulders," Cirules writes. In his first decade there, he goes on, Hemingway spent his time "exploring the streets and taverns, observing, listening, inebriated at times, on nights of drinking, on nights of cockfights, womanizing in the most splendid places, and acquiring habits that would lead him hopelessly to seek refuge on the fifth floor of a peaceful and protective little hotel on Obispo Street" (the Ambos Mundos).

To me, Cirules' Hemingway is a blend of the man I knew, his fictional characters (especially Thomas Hudson of Islands in the Stream), local lore and the waning memories of aged locals. "Until 1936 there was an intense and scandalous affair between the writer Ernest Hemingway and the voluptuous Jane Mason," Cirules writes, naming a young woman who was then married to the head of Pan Am in the Caribbean. She and Hemingway, the author says, spent four months together on the Pilar, cruising the northern coast of Cuba.

This affair has been the subject of speculation—part of the Hemingway lore—but if it ever took place, it must have been uncommonly discreet. There was certainly no scandal. And however Hemingway may have acted as a young man, the man I knew was slightly shy and surprisingly puritanical.

Cirules and his wife, María, took me to Havana's Barrio Chino, or Chinatown, where Hemingway used to favor the cheap eateries. Enrique drove us in his 20-year-old Russian-French car, which hiccuped seriously each time it started. Near the restaurant, María pointed to the imposing Pórtico del Barrio Chino (Chinatown Gate), erected in 1999 and paid for by the Chinese government. (Since Cuba began relaxing its rules on foreign investment in the 1990s, the Chinese have funded several Chinatown renovation projects.) We ate a simple but tasty meal, paying $18 for four people, about half what a tourist restaurant would charge.

After dinner we went to the Hotel Nacional, the historic landmark built in 1930, favored by Winston Churchill and still Havana's premier hotel, to meet Toby Gough, a 37-year-old British impresario who travels the world seeking exotic dancers to put into stage shows he produces in Europe. Gough lives in Havana a few months of the year. In the last half-decade, he has taken his pre-Castro-style productions—The Bar at Buena Vista, Havana Rumba, Lady Salsa—to a dozen countries with, he boasts, astonishing success. "Cuba sells the image of Cuba in the '50s the whole time while rejecting its values," Gough told me. The Cuban government gives its blessing to such enterprises because they stimulate tourism. I suppose that for a Communist country in dire need of foreign exchange, the image of a decadent capitalist playground helps pay the bills.

Gough calls his new show Hemingway in Havana, and it features an Irish-Canadian actor/writer Brian Gordon Sinclair as a Hemingway surrounded by Cuban dancers. Gough said he "took the music of Hemingway's era, the mambo, the cha-cha-cha, flamencos during the bullfight stories, a song about fishing, a song about drinking, and then contrasted the local Cuban people then and now with a contemporary dance piece." Apparently, the Cuban Hemingway has become an export, like Cuban rum, cigars, music and art.

Gough recently staged a private performance of the show for Sir Terence Conran, the furniture retailer (Habitat) turned nightclub-and-restaurant entrepreneur, who, Gough said, was considering it for his London El Floridita. It came as news to me that Hemingway's old haunt had been franchised.

On the long flight home I had time to compare the Cuban Hemingway, with whom I'd spent the last few days, with the Hemingway of my memories. The man I knew did not belong to any country or person (though maybe to his alpha male tabby cat, Cristóbal Colón). He enjoyed the land, the sea, great ideas and small ones too, plus sports, literature and everyone who plied an honest trade. He let nothing interfere with his work, not even drink. He had an excessive love for animals and would show unusual kindness to people, but nothing could match his anger.

I felt lucky never to have incurred that wrath. He could be ruthless or cruel with friends and, especially, family if they did not meet his expectations. I watched the manuscript of his brother Leicester's autobiography go up in flames in the burn barrel on the terrace outside the library while Ernest muttered, "Blackmail." I noted the ostracizing of his son—my future husband, Gregory—after a series of false starts and academic missteps that would be explained only much later as the result of deep emotional distress. And I remember Hemingway venting, in some of the letters I transcribed in the finca library so long ago, what can only be called hatred for his third wife, Martha Gellhorn. (It was she who had found the finca, which the couple first rented, then purchased, to celebrate their 1940 wedding.) If her name, or Gregory's, came up, even accidentally, everyone in the house walked on tiptoes and spoke in whispers.

Hemingway was a born teacher and lifelong student—of nature, sports, history, of everything he engaged in—and his sense of humor is often overlooked. (He loved wordplay, as you might expect of a writer, but he was also a gifted mimic.) He taught me to fish for marlin in the Gulf Stream, to evaluate a fighting cock, to shoot a rifle—then told me what to read, and how good writing must be based on an intimate knowledge of a subject. My apprenticeship may have been the most transformative any young secretary has ever experienced.

On the flight home, I also thought about some of the things the three septuagenarian Gigi Stars had told me. Baseball was not part of my finca experience, but after Ernest, Mary and I left Cuba in July 1960 and made our way to New York City, one of the first people I met was Mickey Mantle. We had gone to Toots Shor's restaurant for a drink before heading to Madison Square Garden to watch one of heavyweight boxer Archie Moore's last fights. No sooner had Shor greeted Hemingway than the restaurateur brought over the Yankees slugger. When Mantle shook my hand, all I saw was a handsome young man. I was oblivious to his celebrity.

Years later, while Greg and I were married, he often took our sons to Central Park, where he taught them the finer points of baseball. I knew nothing of the Gigi Stars, but my children would often remind me that I had once met Mickey Mantle. In time, we became a Yankees family; in spring and summer, we took the number four subway north to Yankee Stadium to cheer them on. Not once, to me or to his sons, did Greg ever speak of the far-off days in Cuba when he had been a baseball star himself, had had a team named after him and had been his father's favorite son.

Valerie Hemingway, author of Running with the Bulls: My Years with the Hemingways, lives in Bozeman, Montana. Photographer Robert Wallis is based in London.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.