Hike in the Footsteps of Teddy Roosevelt

Energetic Teddy was a hiking fanatic—follow his trail on these trips

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/1c/1a1c8a4a-6f1a-474c-bac8-e7d8908a582d/muir_and_roosevelt_restored.jpg)

When Theodore Roosevelt took office as the United States’ 26th president, he was only 42, the youngest president in the history of the nation. He was also a fanatic for the outdoors, and was actually heading back from a hike when his predecessor, President William McKinley, took a turn for the worst after an assassination attempt and died.

The presidency and life at the White House didn’t stop Roosevelt from enjoying a life outdoors, though. He had a tendency to take ambassadors and friends with him on intense hikes around Washington, D.C., and across the country. “What the President called a walk was a run: no stop, no breathing time, no slacking of speed, but a continuous race, careless of mud, thorns and the rest,” French ambassador Jean Jules Jusserand detailed in his memoirs.

January 6, 2019, marks the 100th anniversary of Roosevelt's death. Though there are many wilderness locales that celebrate Roosevelt’s nature-loving legacy—like the Theodore Roosevelt Area of the Timucuan Preserve, Theodore Roosevelt Island and Theodore Roosevelt National Park—the spots below can also claim his footsteps.

Tahawus, New York

On September 6, 1901, President McKinley was shot. At first all seemed well—Roosevelt had gone to his bedside in Buffalo, but left after seeing the situation improving. Roosevelt met his wife on his way to the Adirondacks, and they stopped in Tahawus, New York, which is now a ghost town. While there, he decided he wanted to climb nearby Mount Marcy. Today the trailhead where Roosevelt kicked off his hike is called the Upper Works trailhead. A 21-mile round-trip path leads up the mountain, with a gradual slope up and an often-muddy trail.

Roosevelt had just begun his trek down from the summit when he heard that McKinley’s condition had gotten much worse. He instantly headed back to Tahawus and then began the trip back to Buffalo. On the way there, McKinley died, leaving Roosevelt as the new president.

Rock Creek Park, Washington D.C.

When Roosevelt was in office, this was one of his favorite spots to go hiking. He’d often suggest a walk to members of his “tennis cabinet” (a group of informal advisors) or to foreign ambassadors visiting the U.S. Follow the 3.5-mile Boulder Bridge hike through the part of the park Roosevelt frequented. He lost a gold ring at the bridge itself, leaving an ad in the paper for its return: “Golden ring lost near Boulder Bridge in Rock Creek. If found, return to 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Ask for Teddy.”

On one hike in this area, he brought along Jusserand—who was said to be the only one who could actually keep up with Roosevelt on his hikes. The two became fast friends after an incident on the hike. The president, intending to cross Rock Creek, stripped naked in order to keep his clothes dry for when they emerged on the other side. Jusserand reluctantly did the same, but insisted he keep wearing a pair of lavender gloves; he told Roosevelt it was because if they met some ladies while nude, he still wouldn’t be underdressed.

Yellowstone National Park

In 1903, two years into the presidency, Roosevelt launched his first cross-country trip out to the western U.S. On the way, he stopped at Yellowstone National Park for a hiking and camping trip with naturalist and essayist John Burroughs. The two covered a substantial section of the park, starting in the northeast and heading to see the geysers, then checking out Fort Yellowstone, Mammoth Hot Springs, Tower Falls and other geologic beauties.

“While in camp we always had a big fire at night in the open near the tents, and around this we sat upon logs or camp stools, and listened to the President's talk,” Burroughs wrote for The Atlantic in a 1906 essay about the trip. “What a stream of it he poured forth! And what a varied and picturesque stream—anecdote, history, science, politics, adventure, literature; bits of his experience as a ranchman, hunter, Rough Rider, legislator, Civil Service commissioner, police commissioner, governor, president,—the frankest confessions, the most telling criticisms, happy characterizations of prominent political leaders, or foreign rulers, or members of his own Cabinet; always surprising by his candor, astonishing by his memory, and diverting by his humor.”

Yosemite National Park

After Yellowstone, Roosevelt headed out to California and Yosemite National Park, where he would meet naturalist and author John Muir for another guided camping trip. Roosevelt invited him along on the trip through a letter:

My dear Mr. Muir:

Through the courtesy of President Wheeler I have already been in communication with you, but I wish to write you personally to express the hope that you will be able to take me through the Yosemite. I do not want anyone with me but you, and I want to drop politics absolutely for four days and just be out in the open with you. John Burroughs is probably going through the Yellowstone Park with me, and I want to go with you through the Yosemite.

Sincerely yours,

Theodore Roosevelt

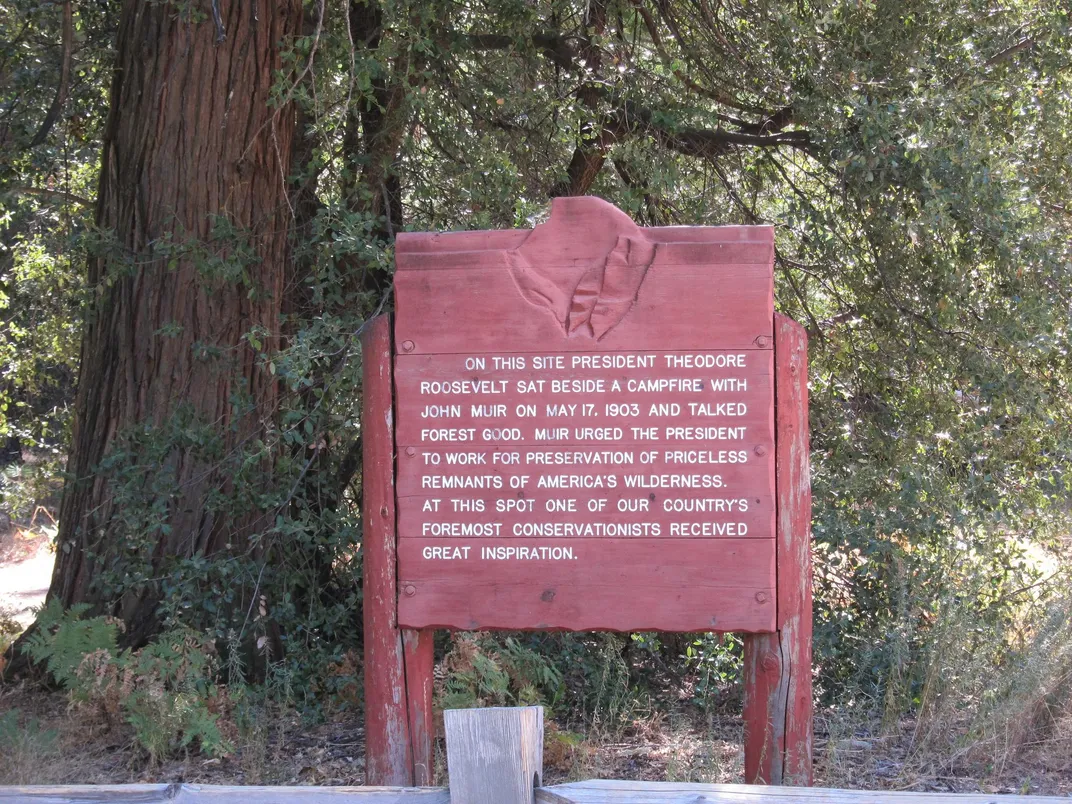

Muir replied about two weeks later with an emphatic “yes.” The two started their journey camping in Mariposa Grove to see the giant sequoias. From there they headed to Glacier Point, Washburn Point, Hanging Rock and Bridalveil Fall. At Bridalveil Fall, hikers today can see a marker—the only official one—that designates the spot where Roosevelt and Muir camped for a night.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)