How Charles Dickens Saw London

Sketches by Boz, the volume of newspaper columns that became Dickens’ first book, invokes a colorful view of 19th-century England

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Sketches-by-Boz-Seven-Dials-631.jpg)

Seven Dials, in central London, is a good place to people-watch. Outside the Crown pub, ruddy men laugh loudly, sloshing their pints; shoppers’ heels click on cobblestones; and tourists spill bewildered out of a musical at the Cambridge Theatre. A column marks the seven-street intersection, and its steps make a sunny perch for gazing on the parade.

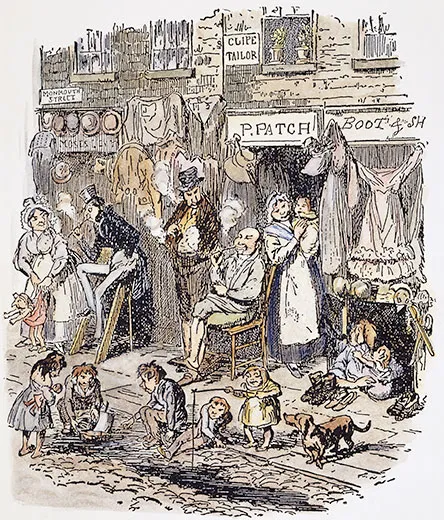

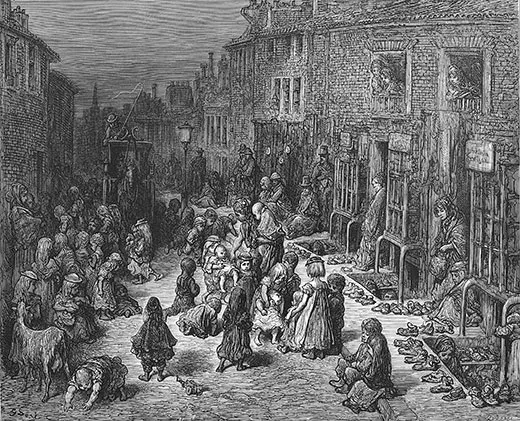

Charles Dickens soaked up the scene here too, but saw something utterly different. Passing through in 1835, he observed “streets and courts [that] dart in all directions, until they are lost in the unwholesome vapour which hangs over the house-tops and renders the dirty perspective uncertain and confined.” There were drunken women quarrelling—“Vy don’t you pitch into her, Sarah?”—and men “in their fustian dresses, spotted with brick-dust and whitewash” leaning against posts for hours. Seven Dials was synonymous with poverty and crime, a black hole to most Londoners. Dickens stormed it with pen and paper.

It’s hard to conjure the notorious slum from the column steps today. Passing reference to the area’s history in a guidebook is abstract, leaving you with a cloudy image of sooty faces. But read Dickens’ description of the Dials in Sketches by Boz, and it comes to life. Newspaper essays collected into his first book, in 1836, Sketches follows a fictional narrator, Boz, who roams the metropolis and observes its neighborhoods, people and customs. Detailed and lively, it’s the closest we have to a film reel of early 19th-century London.

Read today, Sketches leads us on an alternative tour of the city. “Much that Dickens described is still there and looks at it did in his prose, despite the Blitz and modernization,” says Fred Schwarzbach, author of Dickens and the City. “He teaches us to read the city like a book.” Making the familiar fresh, he attunes us to its richness and encourages imagination.

Dickens’ columns made a splash when they were seen in multiple periodicals from 1834 to 1836, culminating in the publication of Sketches by Boz. Their popularity led to the commission of the Pickwick Papers, launching Dickens’ literary career. Already a successful Parliamentary reporter, he brought a journalistic perspective to the essays. Though as colorful as his novels, they were rooted more firmly in fact, like narrative nonfiction today, and astounded critics with their realism. Dickens fudged the details, but contemporaries felt that he captured the essence of metropolitan life.

Other writers had covered London’s history or set stories there, but had never made it the subject itself. Dickens was concerned only with the here and now. “He looked at London in a very original way,” says Andrew Sanders, whose new book Charles Dickens’s London follows the author around town. “London is the chief character in his work.” It had grown exponentially in the 20 years before Sketches, from one million residents in 1811 to 1.65 million in 1837. To Londoners, it became unrecognizable, foreign. Walking tirelessly across London and jotting down his observations, Dickens fed their curiosity about the new city. He was, Victorian writer Walter Bagehot said, “like a special correspondent for posterity.”

Dickens’ wry sense of humor imbues the essays, making Boz an engaging narrator. Enthralled, annoyed and amused by city life, he sounds like us. The streets are vibrant and dreary, crowded and isolating, and make endlessly fascinating theater. Describing a packed omnibus ride, he had the tone of a jaded New York subway rider: Pushed inside, “the newcomer rolls about, till he falls down somewhere, and there he stops.”

As we do, he imagines stories about strangers in the street. One man in St. James’s Park probably sits in a dingy back office “working on all day as regularly as the dial over the mantelpiece, whose loud ticking is as monotonous as his whole existence.” This man, like others in the book, signifies a new urban type, chewed up by the city and anonymous.

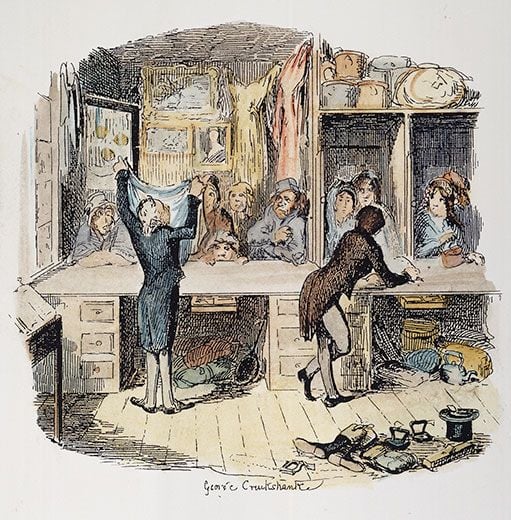

Some places Dickens visited have disappeared. One of the most evocative essays visits Monmouth Street, absorbed into Shaftesbury Avenue in the 1880s (and different from the current Monmouth Street). In the street’s secondhand clothing shops, “the burial-place of the fashions,” Dickens saw whole lives hanging in the windows. A boy who once fit into a tight jacket then wore a suit, and later grew portly enough for a broad green coat with metal buttons. Now the street is a ghost itself.

Another lost corner of London is Vauxhall Gardens on the south bank of the Thames, a pleasure ground long paved over. It was a different world from the gloomy postwar developments that now line the river: “The temples and saloons and cosmoramas and fountains glittered and sparkled before our eyes; the beauty of the lady singers and the elegant deportment of the gentlemen, captivated our hearts; a few hundred thousand of additional lamps dazzled our senses; a bowl or two of reeking punch bewildered our brains; and we were happy.”

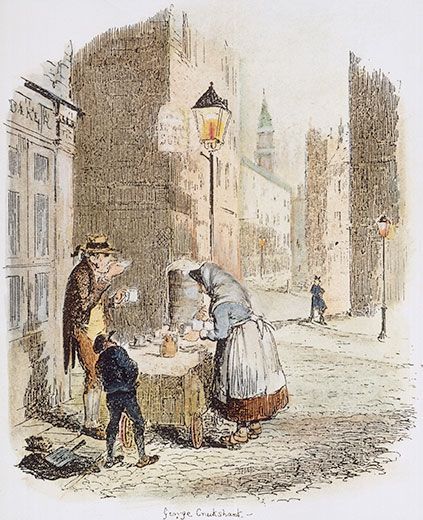

But many of Dickens’ locales still exist, however unrecognizably. What was Covent Garden like when it was the city’s main vegetable market? At dawn the pavement was “strewed with decayed cabbage-leaves, broken haybands. . . men are shouting, carts backing, horses neighing, boys fighting, basket-women talking, piemen expatiating on the excellence of their pastry, and donkeys braying.” Drury Lane was rich with “dramatic characters” and costume shops selling boots “heretofore worn by a ‘fourth robber’ or ‘fifth mob.’” Ragged boys ran through the streets near Waterloo Bridge, which were filled with “dirt and discomfort,” tired kidney-pie vendors and flaring gaslights.

Bring Dickens on a trip to Greenwich, in southeast London, and the quiet hamlet springs alive. The scene sounds less antiquated than you’d expect; the annual Greenwich fair was as rowdy as a college festival, “a three day’s fever, which cools the blood for six months afterwards.” There were stalls selling toys, cigars and oysters; games, clowns, dwarfs, bands and bad skits; and noisy, spirited women playing penny trumpets and dancing in men’s hats. In the park, couples would race down the hill from the observatory, “greatly to the derangement of [the women’s] curls and bonnet caps.”

Even the clamoring traffic jam on the road to Greenwich is recognizable, like a chaotic, drunken crush: “We cannot conscientiously deny the charge of having once made the passage in a spring-van, accompanied by thirteen gentlemen, fourteen ladies, and unlimited number of children, and a barrel of beer; and we have a vague recollection of having, in later days, found ourself. . . on the top of a hackney-coach, at something past four o’clock in the morning, with a rather confused idea of our own name, or place of residence.”

The places Dickens describes resemble in many ways the urban life we know today – crammed with people from different backgrounds and classes. But this modern city only came into being in the early 19th century, and his work was entirely new in both subject and sensibility. It’s hard to appreciate how distinct Boz must have sounded to Londoners then, because his voice has since become ours. Even after 175 years, he makes the city feel fresh.

From This Story

Charles Dickens's London

Sketches by Boz (Penguin Classics)

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.