How the Crew of “Aerial America” Gets its Stunning Shots

A new fusion of camera and captor gives us a bird’s-eye view of America

Cross-country fliers usually nap, read or break out their tablet computers. When Toby Beach flies, he can’t stop looking out the window. “The landscape in this country is just mind-boggling,” he says.

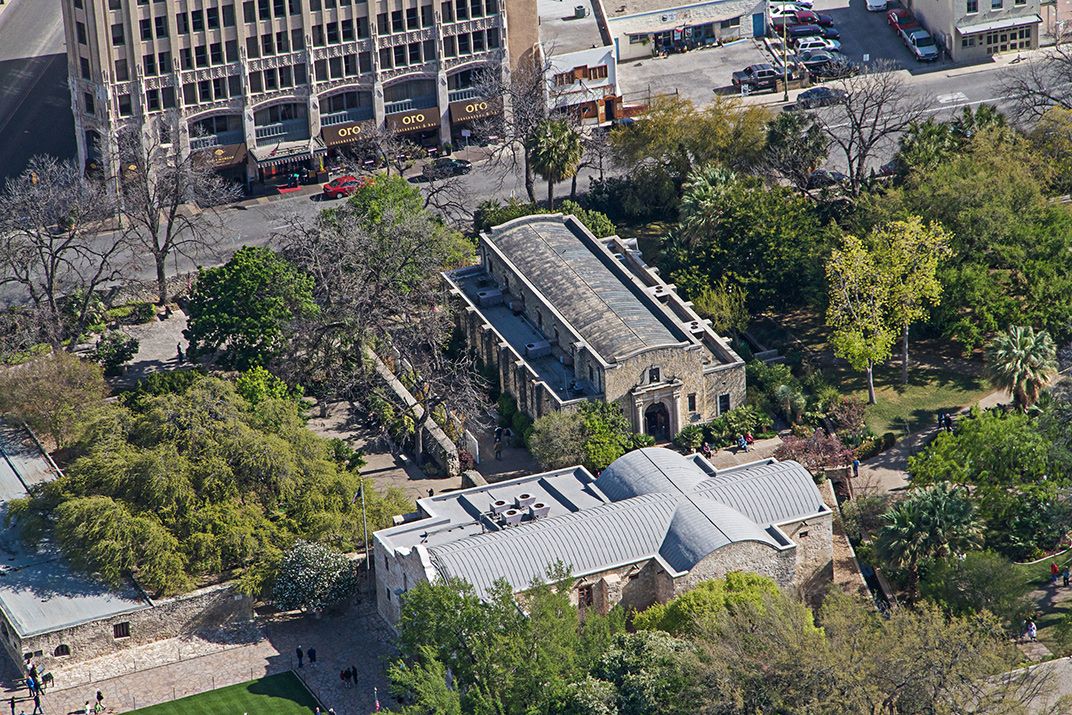

Beach should know; he’s on his way to spending an average of 35 hours airborne over each of the 50 states—and he will not qualify for a single frequent-flier mile. He’s the director and producer of the Smithsonian Channel’s “Aerial America,” which will begin its fourth season on February 23 as one of the channel’s most widely viewed programs. “Everyone can go on Google Earth these days and look down,” says Beach, whose previous work includes documentaries on wildlife and on film actors. The series offers a different perspective: “You’re neither on the ground nor looking from a satellite. You’re in three-dimensional space.”

The idea for the series came from David Royle, the channel’s executive vice president for programming and production. “I had seen some aerial programming in Europe that showed the great monumental sites, like Stonehenge and Versailles,” Royle says. “But I thought of the great American painters of the early 19th century, who turned their backs on the European tradition of painting grand buildings or objects to paint the American landscape, which they considered the equivalent. I thought we could tell the story of America by merging its history with its landscape.”

The “three-dimensional space” Beach mentioned is a result of advances in high-definition videography and helicopter rigging that allow for degrees of depth, clarity, climbing, swooping and zooming that would have been unimaginable a few years ago. Before, Beach says, aerial videographers either took off the helicopter’s door, strapped themselves in and trained a hand-held camera outward, or they bolted a camera to a hard mount on the helicopter’s nose. Either method limited the camera’s point of view and was prone to shaking.

For “Aerial America,” his crew uses a Cineflex system that consists of a 97-pound lens mounted to a gimbal at the helicopter’s nose and a set of controls operated from inside the cabin; the lens can tilt, roll and rotate 360 degrees, but its gyroscopic stabilizer can hold the image still even if the chopper is being buffeted by 30-knot winds. The system can produce close-up imagery of, say, antelope in New Mexico while the helicopter is flying so high the animals don’t know it’s there. It can also confuse human beings on the ground: Beach recalls that someone in Wisconsin reported that the “Aerial America” helicopter was flying around with a person hanging off the nose—which, he notes, “would be a huge FAA violation.”

Beach, the helicopter pilot and the cinematographer manning the camera controls have to make sure the camera and the copter move in concert, whether they’re taking footage of hikers in the six million acres of Alaska’s Denali National Park or a single groundskeeper manicuring Baltimore’s Camden Yards baseball field. They’ve flown higher than 13,000 feet and lower than a hay bale, Beach says. A New York Times reviewer has noted that “no big-budget hour of television is complete nowadays, it seems, without an establishing aerial shot of a nighttime skyline...[but] ‘Aerial America’ takes viewers’ expectations for dramatic views to an extreme.”

“We try to structure each program so the timeline of the state’s history will be clear,” Beach says. But they also “shoot 21st-century stories and images that can bring history alive.” For instance, he cites Kentucky—featured this season, with Texas, Idaho, Utah, the Dakotas, Wyoming and Nebraska—and its 193-year tradition of commercial coal mining. “We filmed old mines and camps,” he says. “But there’s no better way to show viewers just how much coal there is in the Appalachians than to film mountaintop-removal mining from the air.”

As the program approaches the 50-state mark, Beach tends to take the long view from the director’s seat. “You’re seeing all kinds of formations in the ground that date back 50 million years, or the way that industry has transformed the land, the way that people, just in their daily lives over the last 200 years, have turned empty prairie into cities and towns. It’s pretty moving to see.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.