How New York Made Frank Lloyd Wright a Starchitect

The Wisconsin-born architect’s buildings helped turn the city he once called an ‘inglorious mantrap’ into the center of the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/92/fb/92fb650e-7ed9-41cb-bf76-f07a2c5d313b/nyc_-_guggenheim_museum.jpg)

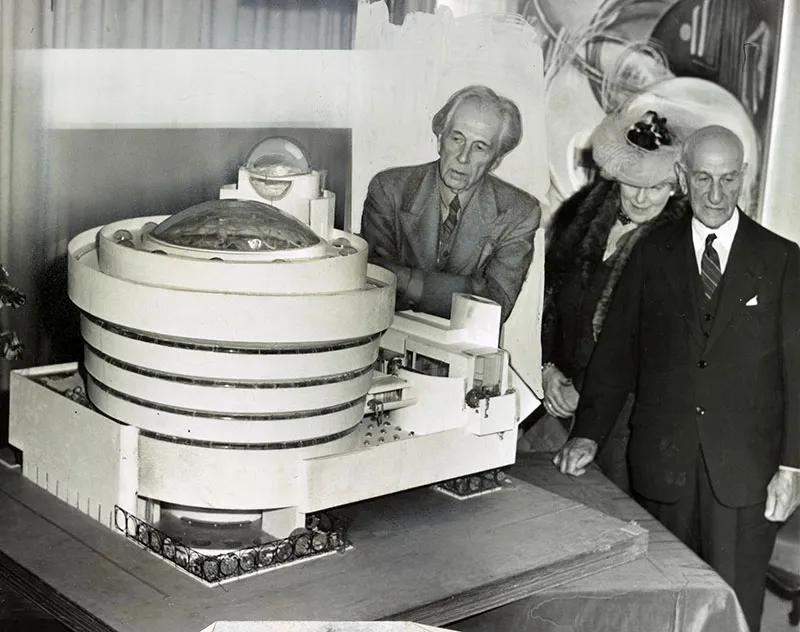

The Guggenheim Museum in New York City is architecture as sculpture—a smooth, creamy-colored, curved form that deliberately defies its square, gray urban context, and succeeds by harnessing the pure abstraction of modernism to the archaic form of the spiral. It proclaims the authority of the architect. It says to the public: It’s my art. Learn to live with it. It stands alone as the built confirmation of the architect’s supremacy as artist.

The Guggenheim is also the defining symbol of the legacy of its designer, the legendary American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Through his work and the force of his personality, Wright transformed the architect into artist—a feat he never could have accomplished without a long, complex and rich relationship with New York City.

Today, Wright is best known as a pop icon, a flamboyant individualist with a chaotic love life who routinely bullied clients and collaborators—all in the service of his powerful personality and homegrown American aesthetic. But there was more to him than that. Wright was the first true star of his field, and his vision and success liberated generations of architects in his wake, from Frank Gehry to Zaha Hadid to Santiago Calatrava, inviting them to move beyond utilitarian function packed in square boxes to explore sculptural forms with autonomy.

Less known is the role New York City played in his vast influence as an artist. Wright complained shrilly about the city, calling it a prison, a crime of crimes, a pig pile, an incongruous mantrap and more, but this was the bluster of someone who protested too much. New York forged Wright’s celebrity as an American genius, resurrected his career in the late 1920s, and ultimately set him up for the glory of his final decades and beyond.

Wright got his start far from New York. Born into a dysfunctional Wisconsin family in 1867, he weathered his parents’ divorce but dropped out of college. He became the righthand assistant of the architect Louis Sullivan, a pioneer in Chicago’s efforts to create a distinctive American architecture, and in the 1890s started his own practice in Chicago, and Oak Park, Illinois.

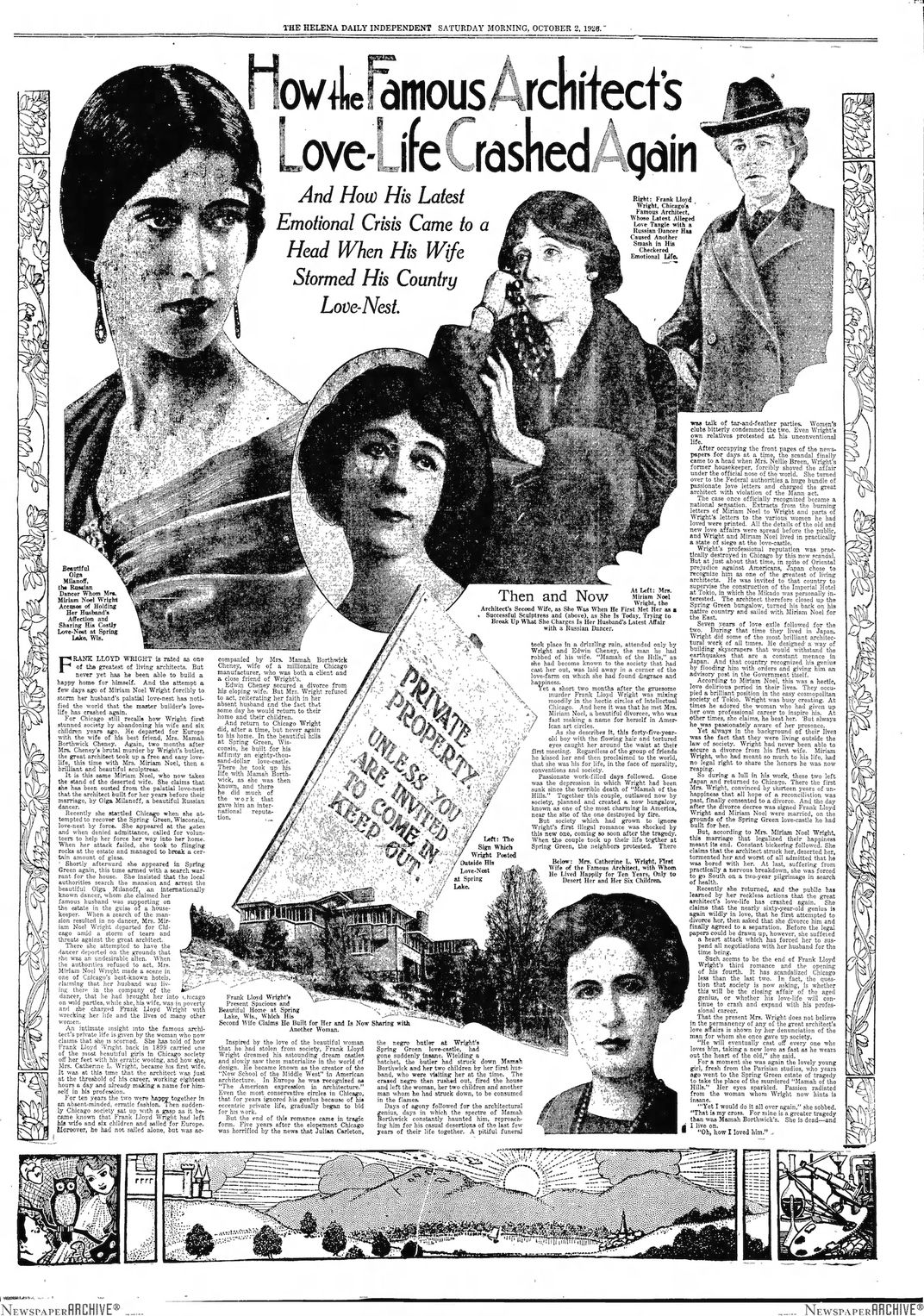

By 1909 Wright had revolutionized domestic architecture, opening up the interior spaces of houses and harmonizing them with the landscape. He spent much of the 1910s in Japan designing the Imperial Hotel. Upon his return to America in the early 1920s, he found his career in shambles and his personal life in disarray, and spent much of the decade trying to reestablish his practice and his personal equilibrium. His brilliant projects went mostly unbuilt, and the yellow press covered his messy divorce and daily exploits. In the early 1930s Wright began to reemerge to acclaim in the public eye. In the last two decades of his life, his built work proliferated, and he rocketed to international fame.

Wright lived almost 92 years, so he had a long time to establish this fame—and he is experiencing one of his periodic resurgences of popularity today. Wright’s houses are once again in vogue (after decades of going in and out of fashion) and two chairs from the early Prairie period recently sold at auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars. What’s more, the architect is enjoying renewed status as a cult figure, revered by his followers for his independence and individualism—the inspiration, at least indirectly, for Howard Roark in Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. Wright’s latest generation of fans are rushing out to buy a recent biography that revisits the tragic and notorious fires at the architect’s compound at Taliesin, his home and studio near Spring Green, Wisconsin. They gather enthusiastically on the Internet, posting snippets of Wright’s writings on Twitter. Some still refer to him reverently as “Mr. Wright.” He’s a cash cow for the eponymous foundation which, having just announced closing his unprofitable school, licenses his name on everything from tea cups to ties.

Wright’s detractors have a lot to talk about these days, too. Wright was the sort of old white male who makes easy target practice, a famously arrogant figure who often alienated the very clients he relied upon to bring his architecture to life. A recent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art reminded visitors of strands of racism and misogyny in his work. Wright and his last wife, Olgivanna, exerted domineering control over apprentices, even dictating who married whom.

But all the focus on Wright’s sensational biography—whether it elevates him to pop icon status or hoists him overboard as a monstrous egomaniac—avoids the serious question: beyond the hype, what is Wright’s legacy? That brings us back to New York.

Although Wright wanted to portray himself as unique and self-created, he was part of a long tradition of seekers that continues today, artists of every stripe, in all media, who recoil at the terrors of New York while seeking to know it, to celebrate it, and to use it to find out who they are. A series of prominent American writers saw New York as a “terrible town” (Washington Irving) with skyscrapers that erupted in a “frenzied dance” (Henry James). For Henry Adams, New York had an “air and movement of hysteria.” Hart Crane, the poet, wrote Alfred Stieglitz in 1923 that “the city is a place of ‘brokenness,’ of drama.”

Interwoven into these complaints was an acknowledgment that New York spurred creativity and transformed artists. Herman Melville badmouthed New York at length. But during his first stay there, from 1847 to 1851, the city’s vibrancy and burgeoning publishing industry turned him from an unknown into a great popular success. Not only was Melville’s career transformed but, according to his biographer, the “pulse” of his energy increased. Melville remained tethered to the city and its publishers for the rest of his life, and he died there.

Wright had a similar response to New York: repulsion and irresistible attraction. He first visited the city in 1909 anonymously but his most transformative experience there began in the mid 1920s when, fleeing his estranged wife, Miriam, he took refuge with his lover, Olgivanna Hinzenberg, and their infant in Hollis, Queens, in 1925. A year later he returned. This time he went to Greenwich Village, home of his sister Maginel, a successful illustrator.

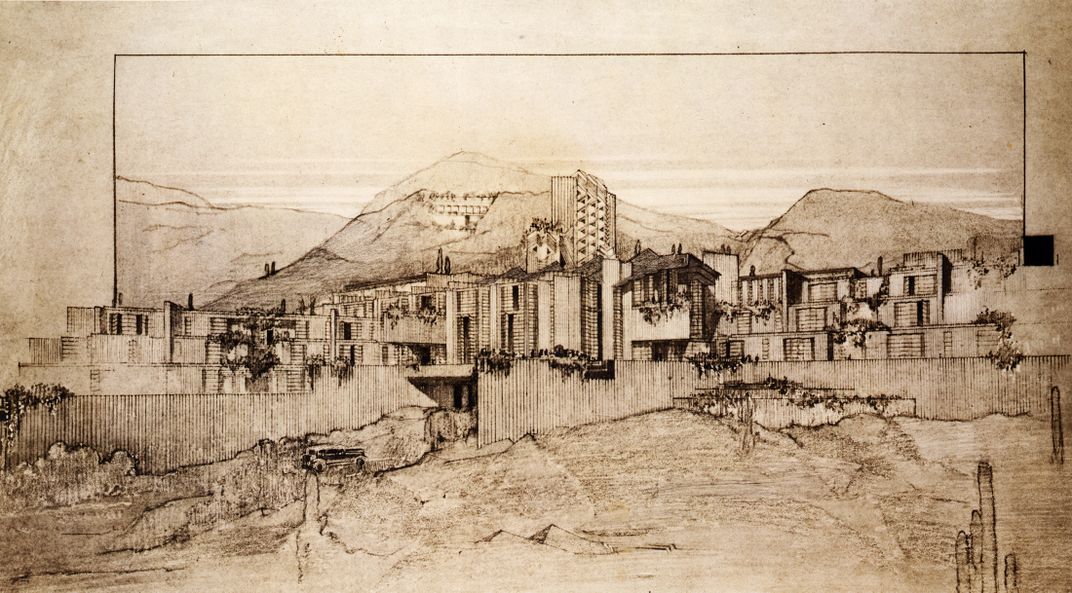

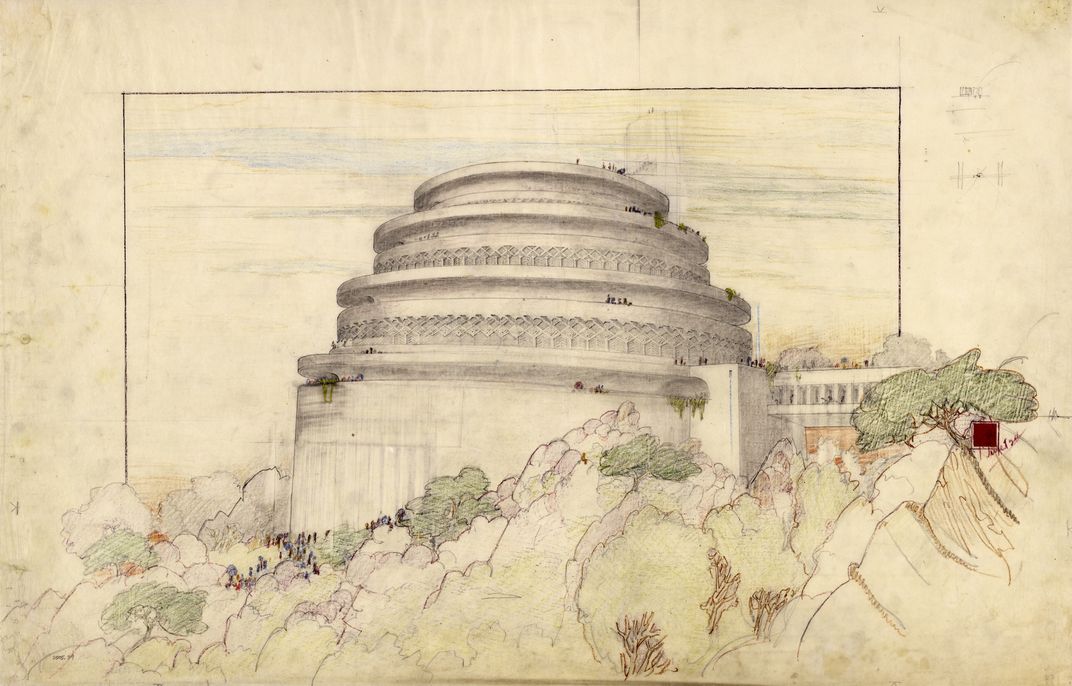

Wright’s stay of several months occurred as he was struggling to rebuild his practice and his reputation. All his projects—from an innovative office building in Chicago to a spiral shaped “automobile objective” for motoring tourists in Maryland—had fallen away. He had high hopes for “San Marcos in the Desert,” a lavish resort in Arizona, but it had no secure funding. Building new projects in New York could be a way out of debt.

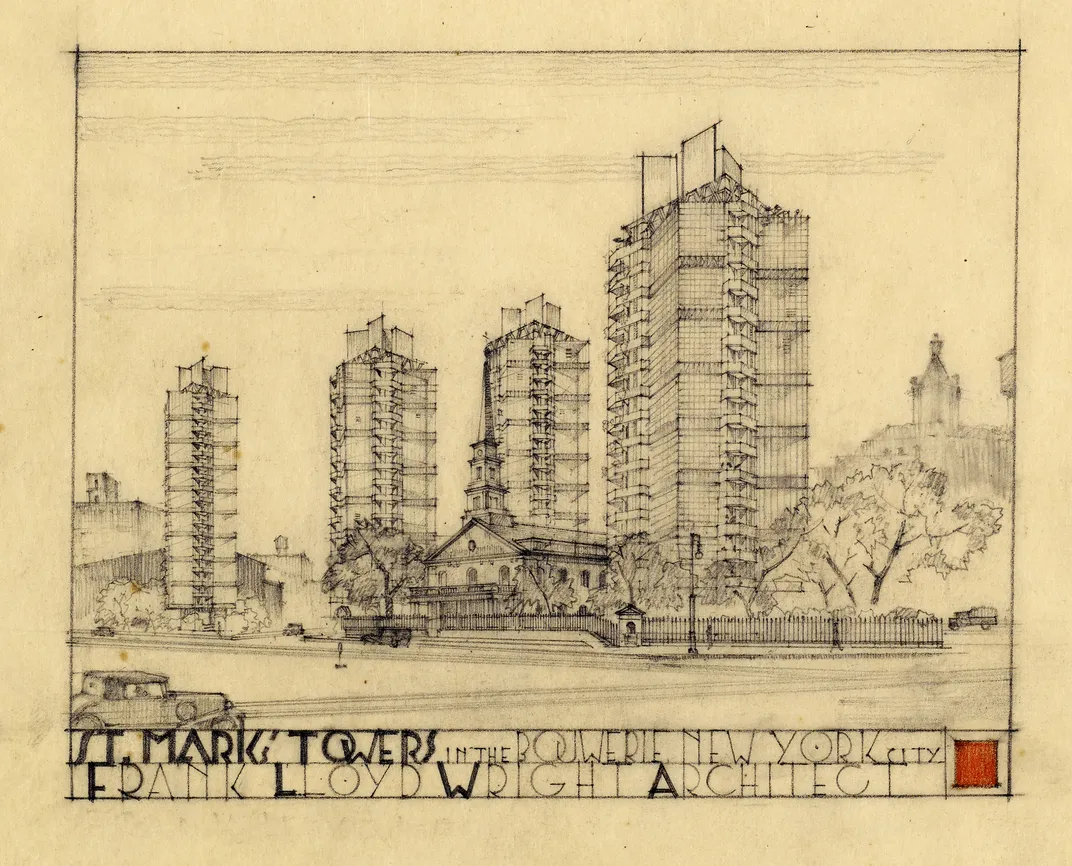

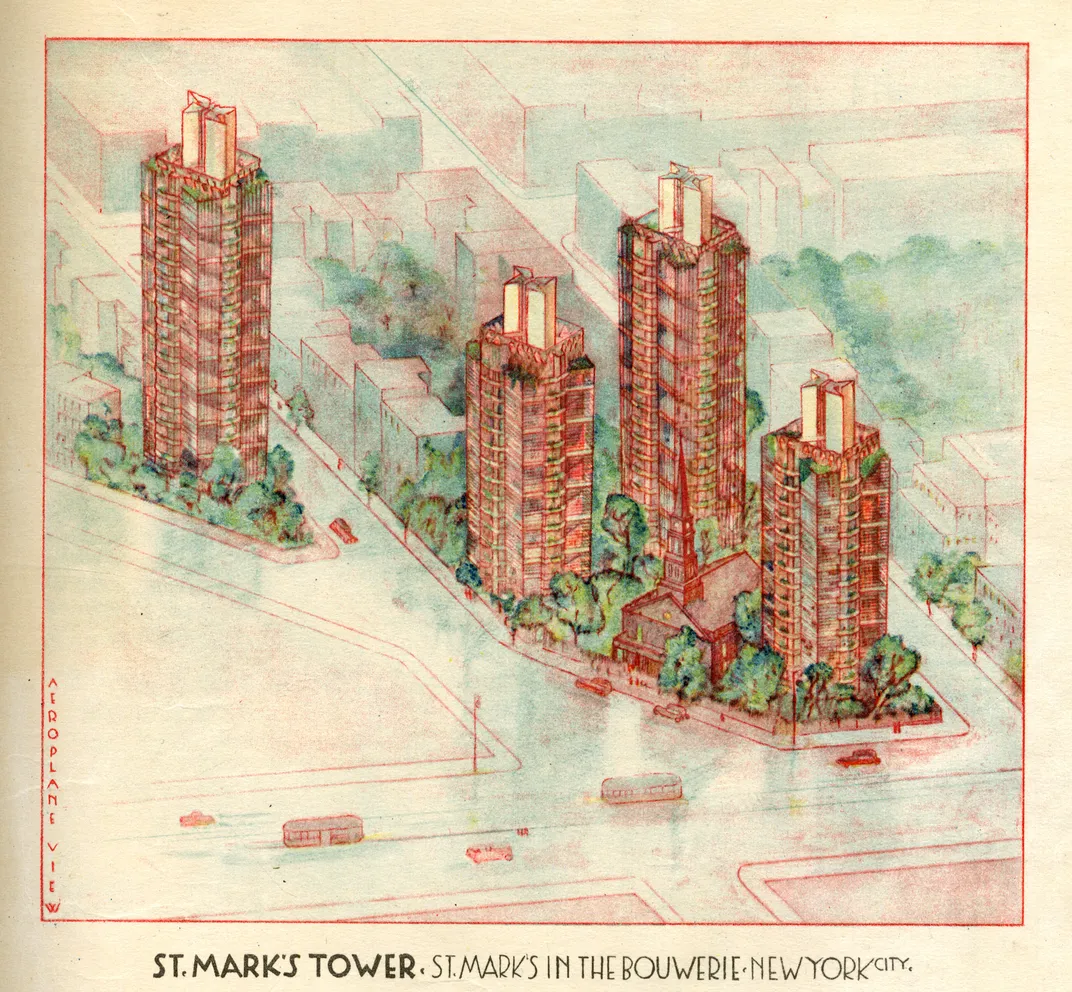

New York offered energy, culture, and connections. His visit to the city enabled him to reconnect with his client and close friend William Norman Guthrie, the iconoclastic rector of St. Mark’s-in-the-Bouwerie at East 10th Street and Second Avenue. Guthrie wanted to reform religion by making it inclusive and global. He invited New York literati to the church, and introduced his followers to rituals and practices such as services from Hindu swamis and Native American leaders, and, to raise cosmic consciousness, Eurythmic dancing by scantily clad young women. Guthrie’s work set the stage for the 1960s counterculture in the East Village.

Wright designed two visionary projects for Guthrie during the 1920s, an immense fantastical modern cathedral, attached to no particular site, and a pinwheeling skyscraper to be located on the church’s grounds. The feasibility of the cathedral and the skyscraper’s scale in the neighborhood mattered little to Wright. Their role was to confirm the architect’s creative imagination. The skyscraper in particular became a vehicle in Wright’s publicity campaign against European modernism from 1930 onward (he pushed the argument that he had originated what Europeans followed). The skyscraper’s model became a set piece in all his exhibitions, and visitors today can see it at the Museum of Modern Art.

At the same time Wright was designing the St. Mark’s projects, he began forging a network of connections that would propel him forward. A circle of young modernists—including the critic Lewis Mumford and the designer Paul Frankl, known for his “skyscraper furniture”—championed and honored Wright. Mumford defended Wright in his writings and would insist Wright be included in MoMA’s epochal International Style exhibition of 1932. Frankl extolled Wright in books and saw to it that the American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsmen recognized the architect with an honorary membership.

The city’s more conservative, established practitioners welcomed him too, if somewhat belatedly. The buzz surrounding Wright led publishers to seek essays and books from him. Wright wrote a series of essays for Architectural Record that articulated the nature of modern materials and building practices. Princeton University published lectures he gave there, in which he expanded his theory of modern architecture. He also wrote for mass market publications like Liberty magazine. Intertwined with the publications were a series of exhibitions of Wright’s work that raised awareness of his architecture domestically and internationally.

By 1932, when Wright’s Autobiography debuted to critical acclaim, the Depression had devastated the careers of most architects, but Wright’s would only advance. He conceived of his masterwork, Fallingwater, in 1936, while he was developing a new type of middle-class American home that he called Usonian. He was one step away from the pinnacle of his career.

Wright wasn’t living in New York when he designed Fallingwater—he worked from Taliesin—but throughout this period he remained connected to the city and its institutions, including MoMA. By 1943, when he received the commission to design the Guggenheim Museum, Wright knew the city and its challenges intimately. The project would encounter problems with the city building department, protests from artists who thought the building might compete with their art, and pushback from obdurate museum directors whose agendas differed from Wright’s and that of the late founder, Solomon Guggenheim.

By the early 1950s Wright and Olgivanna spent so much time in New York that they remodeled and moved into a suite at the Plaza Hotel. Unlike his first visit to Manhattan, this time around Wright basked in glamor. He entertained Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller as clients, gadded about with Hollywood star Ann Baxter (who happened to be his granddaughter), and appeared on television for interviews with Mike Wallace and Hugh Downs. He even showed up on “What’s My Line,” a quiz show where blindfolded celebrities tried to guess the guest’s identity.

Could New York be the Gotham we prize without the Guggenheim? Could Wright have become the figure we know today without New York? No, to both questions. Wright might have always remained identified with the Prairies, but he needed New York to confirm his superstar identity. New York, in turn, needed Wright to announce the future of architecture—for better or worse—from the world capital of culture, and to set the stage for the visionary projects of the 21st century.

Without each other, these two institutions, the city and the man, would be altogether different.

Anthony Alofsin is the Roland Roessner Centennial Professor of Architecture at the University of Texas at Austin. He is the author of Wright and New York: The Making of America's Architect.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.