How Photography Shaped America’s National Parks

Jamie M. Allen explores how conservation and consumerism have impacted America’s natural heritage

Have you ever gotten a postcard from a national park? Chances are the picture that comes to mind—maybe the powerful eruption of Old Faithful spouting up in Yellowstone or the rocky depths of the Grand Canyon—is the same shot that people across the world have seen.

There’s a reason for that. The idea of America’s national parks that's ingrained in the collective consciousness has been shaped through more than 150 years of photographing them, Jamie Allen contends in her new book, Picturing America’s Parks.

You might be surprised by just how important a role photography played in constructing what America thinks of as national parks today. Allen, an associate curator at the George Eastman Museum, weeds through the parks' origins, critically exploring the forces behind those now-iconic visages.

While national parks were created to preserve the country’s natural heritage and allow any person to experience their beauty, few were able to see them in person until the mid 20th century, when improved roads and more accessible travel allowed tourists to experience the images in person. Early stereographs and photography helped justify the original national parks, but they also shaped how they were viewed by the public.

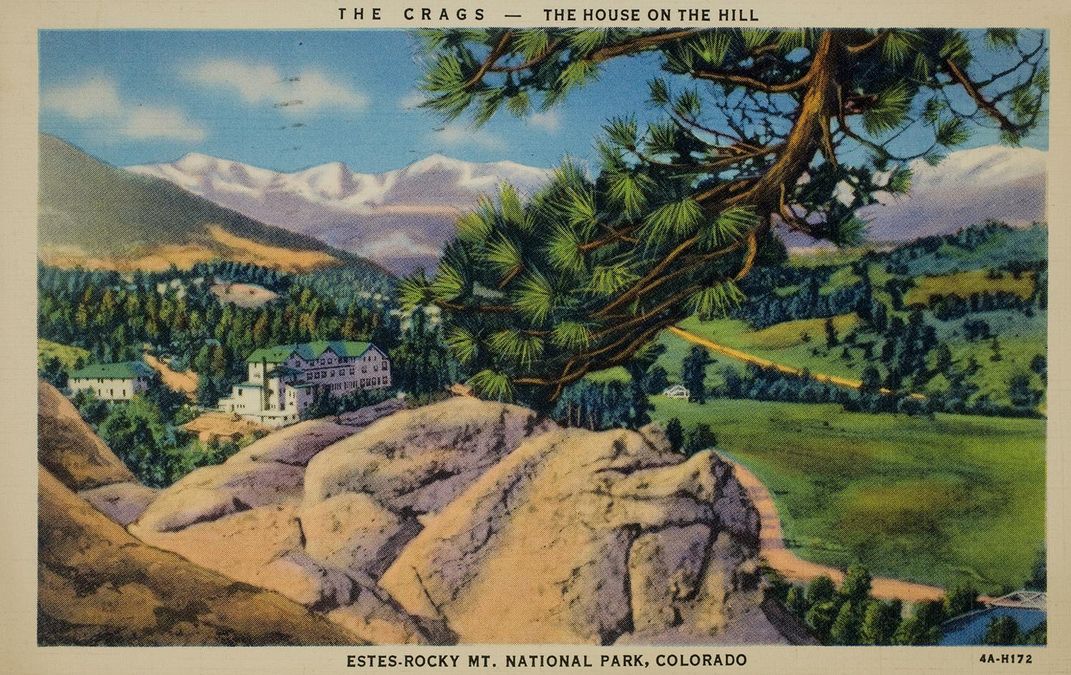

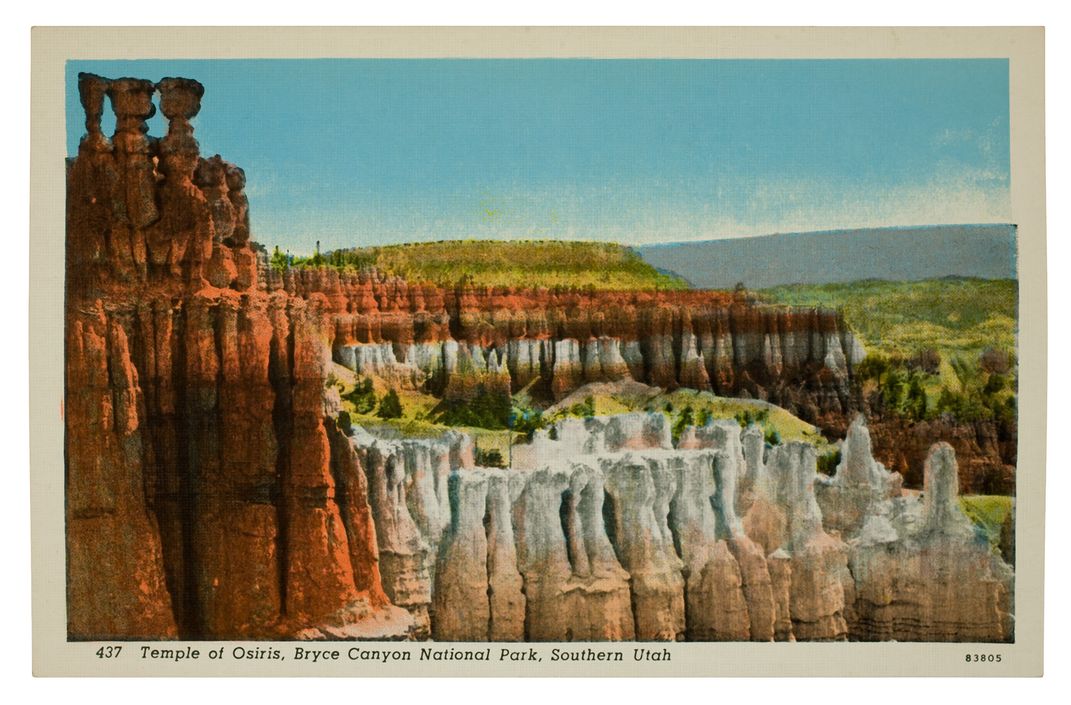

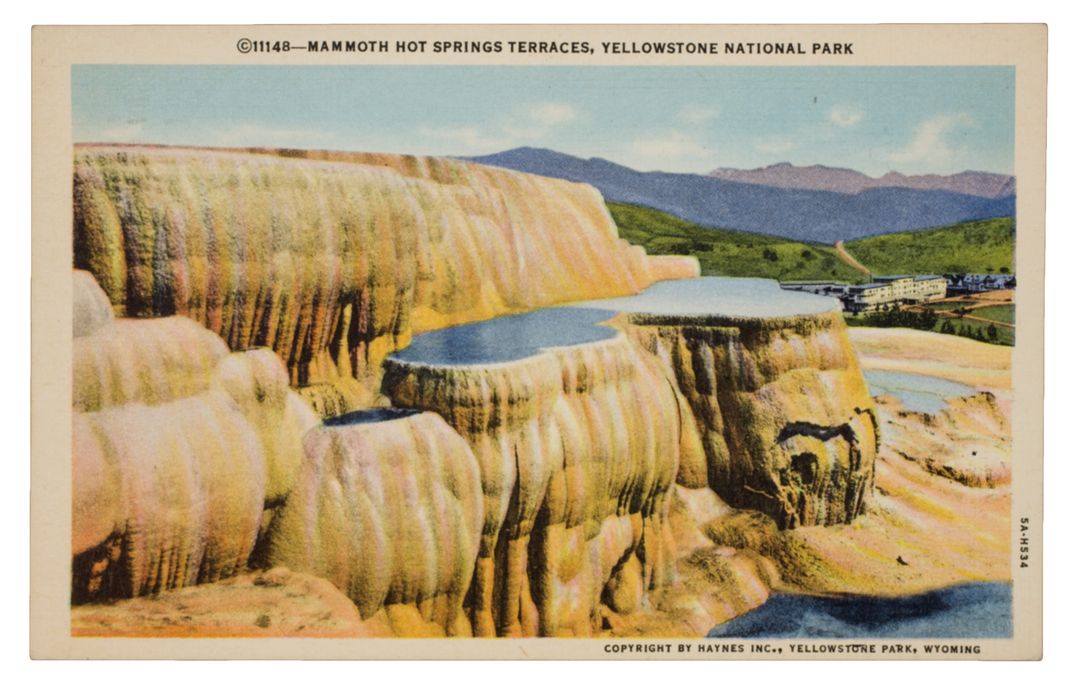

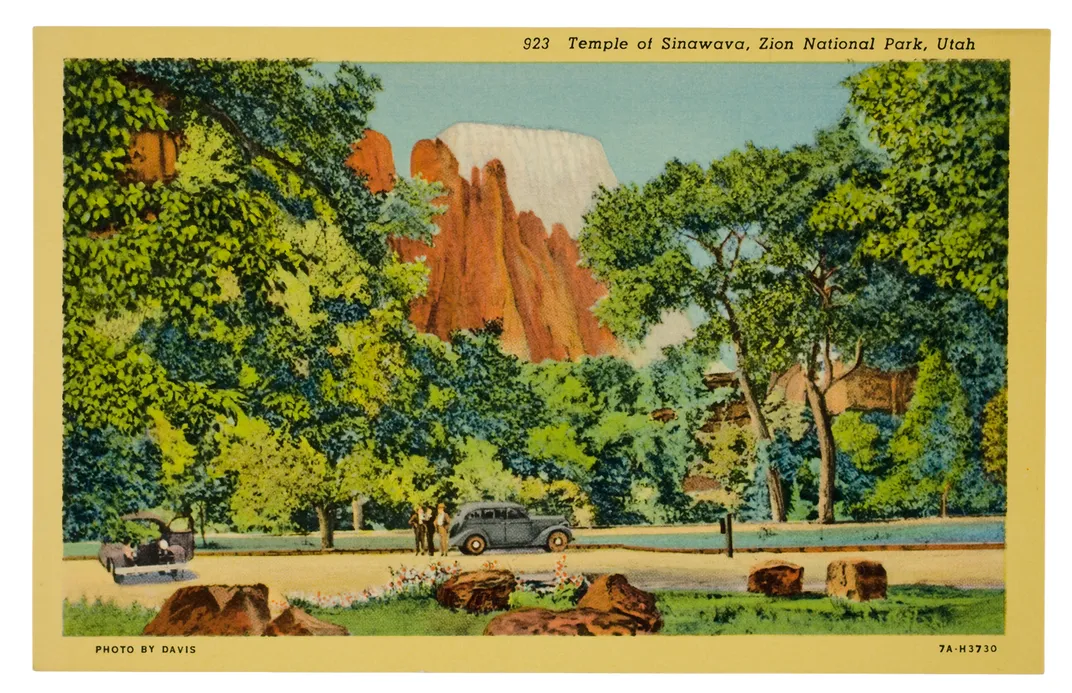

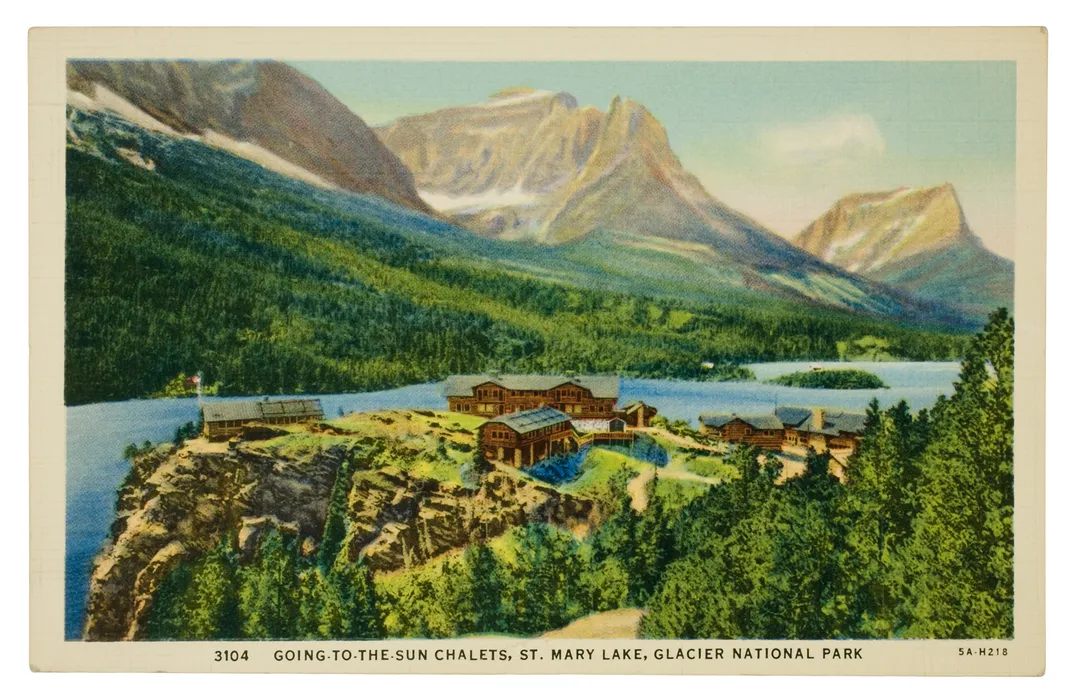

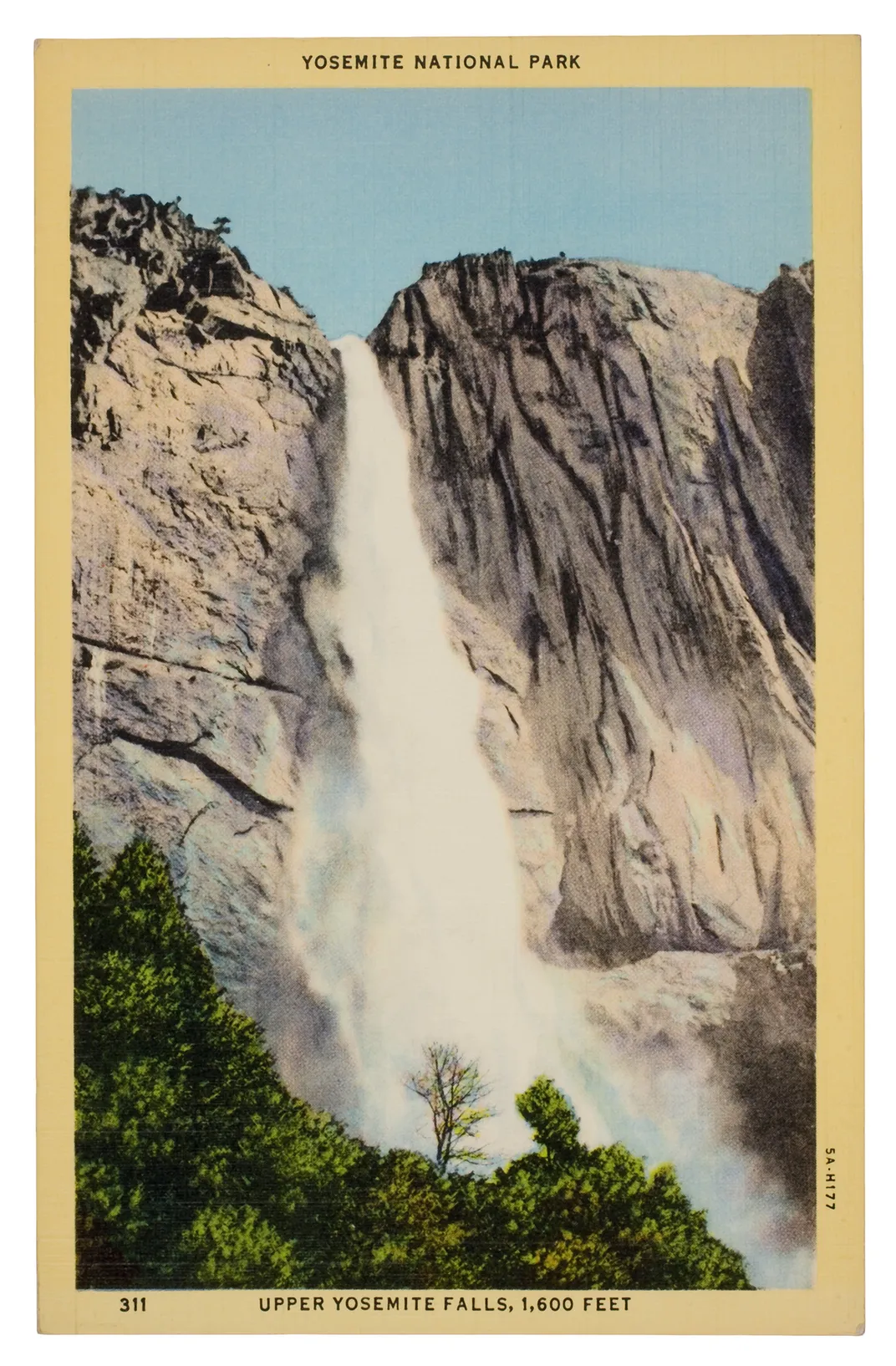

By the 1930s, thanks the invention of the modern car and the construction of paved roads within the parks, people began to make road trips to the parks en masse. Drawn in by the circulating images of the early photography and art that had already captivated their imaginations, people arrived in droves. Advances in photographic technology made the parks seem even more accessible. The National Park Service used the advent of color postcards to highlight park amenities—not to mention the newly paved roads that wound their way through the established photo spots—as a way to encourage more tourism to help pay for conservation efforts.

In the decades that followed, these cemented images of the parks continued to be recycled and reconstructed through new lenses as people explored and examined the parks' legacy. Today, these same images show up transposed through a modern eye, which questions and personalizes these iconic views once again.

Allen discusses the motives of conservation and consumerism at work in her book and exhibition on National Park photography at the George Eastman Museum on view until October 2nd with Smithsonian.com.

How did you get the idea to create Picturing America’s Parks?

A couple of years ago we were kicking around ideas for exhibitions [at the George Eastman Museum]. I brought up an idea of doing an exhibit on photography in the American West because I'm from there. Lisa Hostetler, our curator in charge, said, “Hey, the national parks anniversary is coming up. Is there something we could do in tandem with that?” So I looked into it, and we went in that direction.

This is a story that spans more than a century. Where did you start with your research?

I realized it was really about this journey of exploring these spaces in the 19th century, which then leads [to] them becoming tourist spots—and tourism really drives the understanding of what these spaces are. [Then] preservation comes into being and photographers like Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter start to look at how we can promote these spaces through photography and make them known so that people want to preserve them. All of that, of course, is coupled with art photography all along the way.

Conservation has such a through line in this story of photographing the parks. Can you talk about the evolution of conservation photography within the parks?

Our national parks system is all based on this idea of preserving this land so it's not bought up by individuals and changed into spaces we can no longer enjoy out of natural spaces. By the time cars roll around, we're really changing these spaces. We're putting fences in them and adding roads in them and preserving them, but also changing them to make them easily accessible to people. [It's] kind of a double-edged sword—in a way we are affecting those spaces, good or bad.

I loved how you showed the way people are talking about the parks today, like the National Park Service’s #findyourpark campaign. How has the conversation today become more inclusive through photography?

I think there is a way of speaking about it that helps people take ownership of it in a different way than they did before. The parks have always been a national pride, but as you encourage people to take individual ownership of the spaces, it helps people connect to them in a different way.

As you traced the history of photographing the parks, were there any photo trends that surprised you?

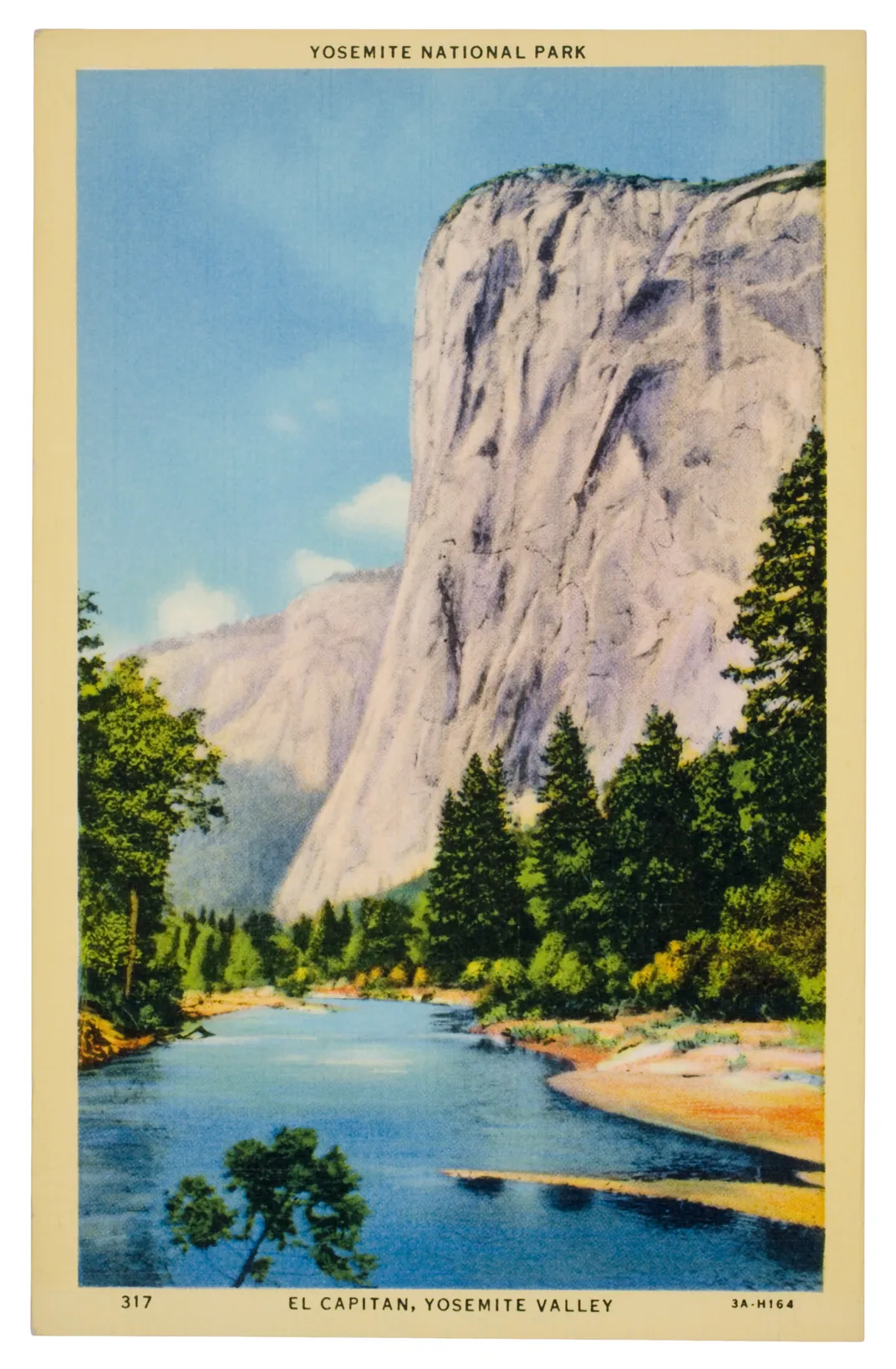

Places like Yosemite, Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon really were established through photography and art. I add art in there because Thomas Moran made a very famous painting of Yellowstone National Park which helped solidify it becoming a national park. It was hung in Congress and people got to understand the color and space and what that area was. As we put images out into the public, we see them proliferate themselves. They get repeated over and over again. Those become the established views that we see. That really shapes the way that we understand these spaces.

There are far fewer images of [newer] spaces [like Pinnacles National Park]. Ansel Adams made images, but they are not as well-known because that park is much newer, so I think as we establish these spaces and set them aside, that's when we see these images come into our collective consciousness.

Did you notice one particular photographic technology that changed the perception of the parks the most?

Photography changed the parks in general, but I do think color really impacted the way that people understood these landscapes. You can see a black and white photograph and understand that the landscape is significant, but if you look at someplace like Yellowstone or the Grand Canyon in color, it really changes your vantage of what that space looks like if you've never been there. You don't understand the peaches and the blues and the greens and the yellows and the pinks that come out of that landscape.

After a long while, I had only looked at pictures of Yellowstone basically in black and white or albumen, and then I saw one that was one of the hot springs and it blew my mind. I hadn't really thought about what that space would look like in color and what it would be like to stand there in color. It really transforms how your brain can understand the space. It's not like I've never seen these photographs before, but it really made an impact on me after sifting through so many photographs to see this thing totally come alive in a totally different way than I'd expected.

How does what’s happening on Instagram and social media today feed into or change the way the parks are seen?

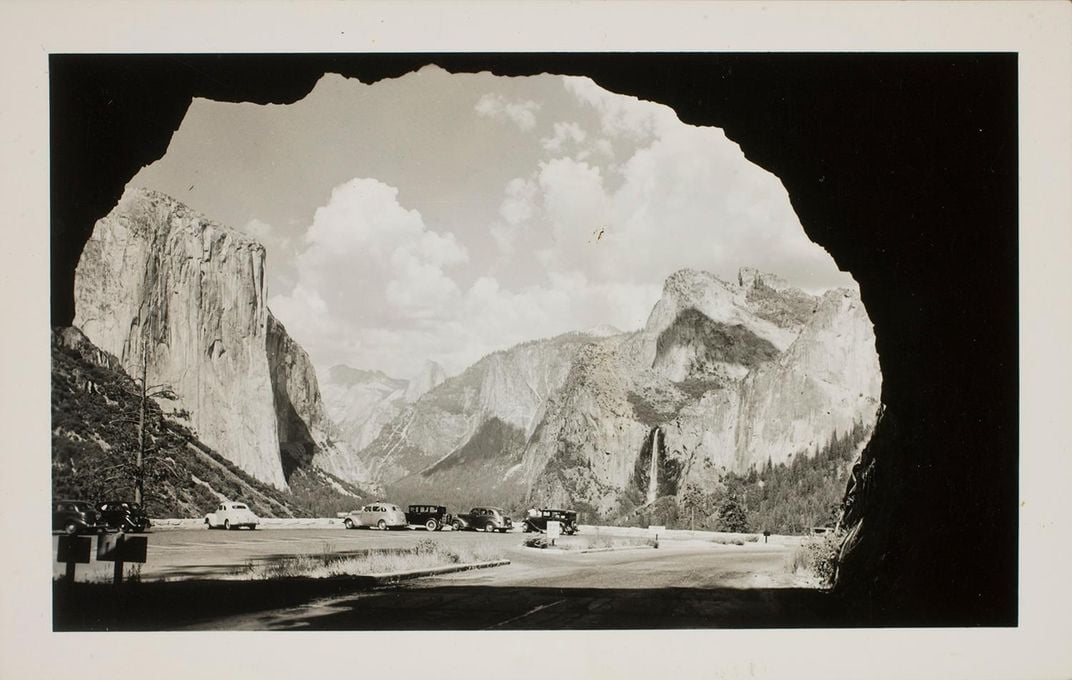

It's interesting to see people try to place themselves in those scenes, and what they're doing mimics what's always been done. There's a picture of a gentleman standing in the archway at Yosemite in the tunnel, and when you look through the book you see from the moment that tunnel was created that becomes the vantage that people want to take. There’s something ingrained in our consciousness that makes us approach these things in the same way over and over again.

Coming out of this project, how has your perception of the National Parks changed?

It’s something I still grapple with. In the beginning, I thought setting aside natural spaces was the way to preserve them, but now that I've learned more about how they were set aside and understand the changes that had to be made to those spaces, there's definitely that question—have we done well by populating these landscapes and then setting them aside? We affect everything in those spaces, [for example] the bears that live there – letting them understand what human food is, and making them want to come be part of our campsites. [Then we have to] drive them away from our campsites because it's not good for them to be near us. We put roads through the parks. We've changed water structures of certain areas by putting holes through mountains in order to create tunnels and roads.

After doing all this work, is there a particular park that you now want to visit the most?

Oh man, all of them. I was only able to represent 23 of the 59 parks in the exhibit, so it's really amazing to think about these spaces that we've set aside. Yellowstone and Yosemite both stick out in my mind. I know those are probably two of the most significant spaces. They're the first two that were really set aside. I really want to walk through the landscape and understand what it looks like and see that photographic vantage come into sight. Now that I've seen the photographic vantage so many times, I want to experience El Capitan from other angles.

Would you take that same iconic shot?

I don't know. I'd probably take that shot but I'd also see if there was anything else that wasn't that shot. In one way it's kind of like collecting baseball cards or something—you have to take the shot that you have to, the one that everyone takes, but then you can explore.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.