For much of the day, Turnagain Arm, a waterway that runs just south of Anchorage, Alaska, is relatively calm. Waterfowl go there to roost alongside the chilly waters, which lap gently against the rocky coastline. But for two brief moments during the 24-hour cycle, the water level swells, creating a wave that can reach heights of up to ten feet. Known as a bore tide, the tidal phenomenon has captured the attention of surfers from around the world.

Bore tides aren’t unique to Turnagain Arm, which is a branch of Cook Inlet, a waterway that stretches for 180 miles from the Gulf of Alaska to Anchorage. They occur at any given time across the globe, from the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia, to the Qiantang River in China, where locals have dubbed it the “Silver Dragon." But the Alaska bore tide is by far one of the most dramatic.

Bore tides (also called tidal bores) occur when outgoing water in a river or narrow bay converges with tidal waters coming in from the ocean. High tide happens twice a day (once in the morning and once at night) and is due to the moon’s gravitational pull, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The result is a massive wave, followed by ripples, that travels against the river or bay's current at a speed of up to 24 miles per hour and a height that often puts ocean waves to shame.

“The reason we get bore tides here is because Turnagain Arm is very long and narrow, so it takes time for the water to come in during high tides,” says Travis Rector, Ph.D., a professor in the department of physics and astronomy at the University of Alaska Anchorage. “It takes roughly six hours for the water to come into [the waterway] and roughly six hours for it move back out because [the waterway is] so long.”

The Alaska bore tide also has one of the largest tidal swings (the measured difference between high and low tides) of any bore tide in the world, with a differential measuring about 35 feet between high and low tides. It’s also the only one occurring in the United States. While waves in Turnagain Arm average about two to three feet in height, it's not uncommon to see ones that top out at 12 feet.

All of these superlatives make it particularly riveting to surfers near and far who come to experience the phenomenon in person. What sets bore tide surfing apart from ocean surfing is that, with the latter, surfers have multiple chances each day to catch a wave. If one doesn’t pan out, there are more sets rolling in right behind it. But at Turnagain Arm, surfers only have two shots to surf it each day (during the high tide in the morning and at night), making it a challenge for both novice and experienced surfers alike.

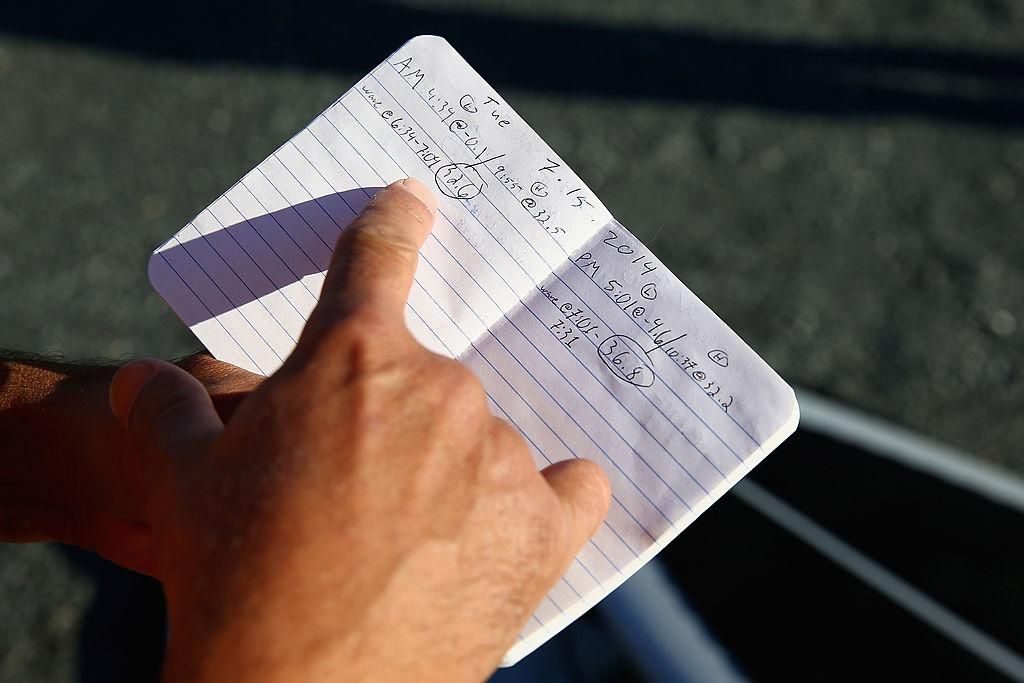

Surfing Turnagain Arm is still relatively new, with the first surfers testing the waters only just a few decades ago. It's only been in the last decade that the sport has gained popularity and national attention, and it still doesn't have nearly the same following as traditional ocean surfing. As with traditional surfing, surfers hoping to tackle the bore tide rely on tidal charts to map out where and when the tide will hit from one day to the next. Tides are based on gravitational forces from the sun and moon, and tides with the largest range occur during the new moon and full moon, which happen roughly once a month. Surfers generally target daytime tidal bores in the new and full moon periods of the month.

Kayla Hoog-Fry, a surf instructor and co-owner of TA Surf Co., a local outfit that offers surf lessons at Turnagain Arm, has been surfing the inlet for the past five years. She spent her childhood waterskiing and wakeboarding the lakes near her hometown of Reno, Nevada, before competing on the University of Alaska’s alpine ski team.

“My friend Pete Beachy [who co-owns TA Surf Co.] introduced me to the Turnagain Arm wave and asked me if I wanted to join him in creating a surfing guide service that introduces people to local surfers,” she says. “Over the years, I’ve gotten in a lot of miles of surfing.”

That’s not always the case with traditional ocean surfing. “You can ride the tide here for several minutes, whereas in the ocean, it could take a few days to get that amount of riding in,” Hoog-Fry says. “As long as you can swim, this is actually a great place to learn how to surf. You don’t have to fight the ocean to [paddle] out, since only one wave comes through. Once you catch the wave, you can either stay lying on your belly [on the surfboard] or stand on your feet.”

A typical surf session looks something like this: Surfers will consult online tidal charts (mobile apps are particularly popular) to figure out when and where the bore tide will hit. Because the location and size of tides can shift depending on the lunar cycle, Hoog-Fry says it's important to consult the charts every time you surf and to not rely on previous surf sessions to determine the size of the wave. Once in the water, surfers begin paddling once they see the wave begin to form. However, at times, the water can be so shallow that surfers can stand in the water and wait until the wave comes before hopping on their boards.

One of the biggest misconceptions, Hoog-Fry says, is that the water is ice cold. “Since this is Alaska, people think it will be freezing,” she says. While that might be the case in the wintertime, when portions of Turnagain Arm freeze over and the prospect of surfing can be dangerous, that all changes come summer, when that part of the state can see up to 19 hours of straight sunshine, making it perfect for surfing. According to Hoog-Fry, with the water temperature climbing above 50 degrees Fahrenheit in the summer, most surfers ditch their wetsuits for their usual swimwear. On average throughout the year, the water temperature stays at around 40 to 50 degrees.

“We provide surfers with equipment like wetsuits and surfboards, and we show them the best places to surf on Turnagain Arm,” she says. Some of the more popular spots include Beluga Point and Bird Point. “We get people visiting from all over, like California and South America. We take them out and show them the best spots and what time to be there [to catch a wave]. Since we surf it every day, we can share that knowledge with them.”

Despite having experience surfing all over the globe, from Hawaii to Indonesia to Sri Lanka, she says she's always drawn back to Turnagain Arm to catch the perfect wave. "So far the tallest one I've surfed was seven feet and lasted several minutes," she says. "It was awesome."

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d0/6e/d06e39ad-7a39-440e-ba8b-36a12eecc67e/alaska_bore_tide_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/fe/d9fe363a-76f8-418a-8f42-a884dc339c67/alaska_bore_tide_header.jpg)