How to Tour Michelangelo’s Rome

The Renaissance artist called art “a wife” and his works “my children.” Visit these five sites in the Italian capital and the Vatican to pay homage to him

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Michelangelos-Rome-portrait-st.peters-631.jpg)

Michelangelo had been on his back for 20 months, resting sparingly, and sleeping in his clothes to save time. When it was all over, however, in the fall of 1512, the masterpiece that he left behind on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome would leave the world forever altered.

Born in 1475 to an impoverished but aristocratic family in Caprese, a hillside town near Florence, Michelangelo Buonarroti grew up with an innate sense of pride, which as he aged, would feed his volatile temperament. When he failed to excel at school, his father apprenticed him to Domenico Ghirlandaio, a Florentine frescoist. Cocky from the start, the 13-year-old Michelangelo succeeded in irritating his fellow apprentices, one so badly that the boy punched him in the face, breaking his nose. But in Ghirlandaio’s workshop, Michelangelo learned to paint; in doing so, he caught the attention of Florence’s storied Medici family, whose wealth and political standing would soon put Michelangelo on the map as an artist and, in 1496, chart his course south, to Rome.

“It’s almost as if Michelangelo goes from zero to 65 miles per hour in a second or two,” says William Wallace, an art history professor at Washington University in Saint Louis. “He was 21 when he arrived in Rome, and he hadn’t accomplished a lot yet. He went from relatively small works to suddenly creating the Pietà.”

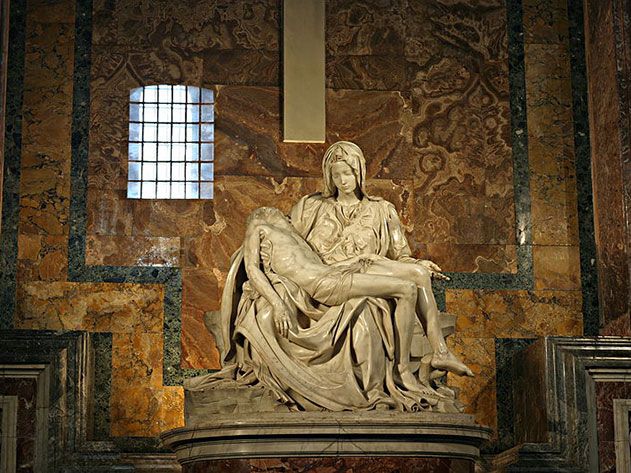

It was the Rome Pietà (1499), a sculpture of the Virgin Mary cradling the body of her son Jesus in her lap, and the the artist’s next creation in Florence, the nearly 17-foot-tall figure of David (1504) that earned Michelangelo the respect of the greatest art patron of his age: Pope Julius II. The 10-year partnership between the two men was both a meeting of the minds and a constant war of egos and would result in some of the Italian Renaissance’s greatest works of art and architecture, the Sistine Chapel among them.

“Pope Julius had, in some ways, an even larger vision—of putting the papacy back on a proper footing. Michelangelo had the ambition to be the world’s greatest artist,” says Wallace. “Both were somewhat megalomaniacal characters. But I think [the relationship] was also deeply respectful.”

Julius II died in 1513, and in 1515, Michelangelo moved back to Florence for nearly two decades. When he returned to Rome in 1534, the Renaissance man had largely moved away from the painting and sculpting that had defined his early career, instead filling his days with poetry and architecture. Michelangelo considered his work on the dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, which dominated his time beginning in 1546, to be his greatest legacy; the project, he believed, would ultimately offer him salvation in Heaven.

Michelangelo Buonarroti died in Rome following a brief illness in 1564, just weeks before his 89th birthday. When a friend questioned why he had never married, Michelangelo’s answer was simple: “I have too much of a wife in this art that has always afflicted me, and the works I shall leave behind will be my children, and even if they are nothing, they will live for a long while.”

St. Peter’s Basilica: Rome Pietà and Dome

Michelangelo was just 24 when he was commissioned to create the Rome Pietà or “pity.” Unveiled during St. Peter’s Jubilee in 1500, it was one of three Pietà sculptures the artist created during his lifetime. When asked why he chose to portray Mary as a young woman, Michelangelo replied, “Women who are pure in soul and body never grow old.” Legend has it that when Michelangelo overheard admirers of the statue attributing it to another artist, he decided to inscribe his name on the Virgin Mary’s sash. It seems he regretted it, since he never signed another work again.

Forty-seven years later, riddled with kidney stones, Michelangelo once again set his sights on St. Peter’s, this time as chief architect of the basilica’s dome. Visitors to St. Peter’s can climb the 320 steps (or take the elevator) to the top of the dome, with views of the Pantheon and Vatican City.

Pope Julius II recruited Michelangelo to design his tomb at St. Peter’s Basilica in 1505, but the work would go on for almost 30 years. Although the structure was supposed to include dozens of statues by the artist and more than 90 wagonloads of marble, after Julius’ death, Pope Leo X—who hailed from a rival family—kept Michelangelo busy with other plans. Only three statues were included in the final product, which was reassigned to the more modest church of San Pietro in Vincoli. Among them, the artist’s rendering of Moses is the clear scene-stealer. With his penchant for drama, Michelangelo referred to San Pietro as, “the tragedy at the tomb,” since he had “lost his youth” in the creation of it.

Sistine Chapel, the Vatican

Michelangelo considered himself to be foremost a sculptor, not a painter, and when Julius II asked him to decorate the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in May of 1508—tearing him away from his work at the pope’s tomb—the artist was less than pleased. A mildew infestation threatened a portion of the work, and Michelangelo pressed his advantage, telling Julius, “I already told your holiness that painting is not my trade; what I have done is spoiled; if you do not believe it, send and see.” The issue was eventually resolved; Michelangelo set back to work on the 343 human figures and nine stories from the Book of Genesis that the 12,000-square-foot masterpiece would eventually comprise.

Michelangelo often locked horns with the Pope about money and sometimes referred to him as “my Medusa,” while Julius, on at least one occasion, allegedly threatened to beat or throw the artist from the scaffolding of the Sistine Chapel if he did not finish his work more quickly. This abuse aside, the painting eventually took its toll on the artist, who suffered a leg injury when he fell from the scaffolding and partial blindness—a result of staring upwards at the ceiling for so long—which forced him to read letters by raising his arms above his head. In 1536, Michelangelo was summoned back to the chapel to paint The Last Judgment above the altar, this time for Pope Paul III.

Piazza del Campidoglio

Campidoglio, or Capitoline Hill, is one of the seven hills Rome was founded upon and has been central to the city’s government for more than 2,000 years. In 1538, when Michelangelo was asked to put a new face on the ancient site, the task was great: it had been used as headquarters for the Roman guilds during the Middle Ages, and required a major overhaul. The artist set to work on the main square, reshaping it as an oval to create symmetry; adding a third structure, the Palazzo Nuovo; and re-sculpting the base of the 2nd century A.D. statue of Marcus Aurelius (which has since been moved to the Capitoline Museums, nearby). Although the piazza wasn’t finished at the time of Michelangelo’s death, it was completed in various stages during the next 100 years using the artist’s designs. In 1940, Benito Mussolini installed the final element, Michelangelo’s brilliant starburst pattern in the pavement.

Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri

As a humanist, Michelangelo believed in the preservation of Rome’s ancient ruins. It was a task he took to heart in 1561, when the artist was hired to convert Diocletian’s massive bath hall, erected in 300 A.D., into a church named for the Virgin Mary. Ironically, the facility’s new destiny was at odds with its original means of construction, which is said to have required the forced labor (and frequent deaths) of 40,000 Christian slaves. The artist’s mission centered on the bath hall’s central corridor, the Terme di Diocleziano, with its eight red granite columns that still remain today. Although Michelangelo died before the church was finished, his pupil, Jacopo Lo Duca, saw the project through to completion.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Michelangelos-Rome-portrait-st.peters-1.jpg)