How Will Covid-19 Change the Way Museums Are Built?

The global pandemic will have long-lasting effects on the form and function of future museums

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/e9/f3e9475a-6831-49b0-b592-814e44f51257/museo_nacional_de_antropologia.jpg)

In the 1890s, New York City waged a war on tuberculosis. The disease, at the time, was the third biggest cause of death in the country. In response, the city created a massive awareness program to drive home information doctors already knew: tuberculosis spread through bacteria that the cup-sharing, sidewalk-spitting public was readily swapping with one another. The awareness program discouraged both spitting in public and sharing drinking vessels—and luckily it caught on throughout the U.S., curbing the spread of the disease.

The response to tuberculosis didn't just change public behavior, though; it also affected infrastructure across the country. Home builders began to construct houses with open porches and more windows, and doctors pushed for outdoor healing where patients could get fresh air and sunlight. Hospitals moved beds outside, and some wards were built as completely open structures. Nightingale wards, named after nurse Florence Nightingale who designed them, emphasized not only fresh air and sunlight, but also social distancing, placing beds in one big room at six feet apart so patients couldn't touch one another. When the 1918 flu arrived, that prompted another change, pushing the distance between beds in Nightingale wards even farther apart, moving from one large ward for everyone to each patient having their own room to minimize infection.

As the world continues to struggle with Covid-19 and prepare for any future pandemics, designers and architects are thinking of new ways to create buildings—ways that account for social distancing and lessen the spread of germs and disease. Schools, for example, could move more toward a learning hub style, where students gather in smaller groups and the walls of the school building itself are no longer as important. Airport terminals are likely to increase in size, with security checkpoints spread out rather than in a single place all passengers must pass through. At the grocery storie, self-checkout lines may disappear, as stores move towards a grab-and-go model, where your items are tracked and scanned as you exit the store and you're charged as you leave. In hospitals, architects expect that most surfaces will convert to virus-killing copper and silver; hands-free technology for doors, lights and trash cans will become the norm; waiting room layouts will change; and unnecessary equipment will be removed from rooms before patients come in.

So, what will museums of the future look like?

While many museums are adapting their physical space and instituting new safety measures to reopen, new museums may see the current moment and take on new forms. Sure, some will maintain current Covid-19 protocols, like timed ticketing and visitor count restrictions, but what else will stick in the long-term? How will people experience museums 10 or 20 years down the road, when proactive design changes to curb the spread of disease have been put in place?

Museum architects, designing everything from interactive science museums and children's museums to art and history institutions, are grappling with both the changing needs Covid-19 presents and some major questions about moving forward in a safe way. Michael Govan, director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and a leader in exploring how the public interacts with art, says a number of issues need to be addressed, among them making exhibits accessible to everyone, even if they don't have the proper device or internet for virtual experiences; eliminating elevators or at least make them more socially distant (LACMA already has one 21-foot-wide elevator that serves this purpose); and handling group tours.

On the whole, going to a museum during the Covid-19 pandemic isn't an especially risky proposition. The Texas Medical Association rates it at a four out of ten, or low-moderate risk, on a scale of how dangerous certain activities are right now. Museums are luckily already one of the more sanitary places to be during a pandemic, according to Bea Spolidoro, a WELL-certified architect (meaning she consistently puts the health and wellness of society at the forefront of her designs) and principal at FisherARCHitecture in Pittsburgh. Her partner, Eric Fisher, worked for four years with Richard Meier and Partners on the Getty Museum, and his top five competition entry for the Palos Verdes Art Center met with much critical success.

“[Depending on the type of facility,] you cannot touch anything in a museum, and [art] museums are fairly quiet,” she says. “You don’t have to raise your voice. So, you can make the case that when you are in the museum, you don’t have to speak loud and project more particles.” That's important, as studies have shown that simply speaking loudly can transmit Covid-19.

But some aspects of the exhibit experience, gift shop and ticketing process could certainly be improved. Here are some of the ways museum design could change as we grapple with a post-Covid world.

Lobby, Ticketing and Traffic Control

Most museums around the world already offer the opportunity to purchase tickets online or through a kiosk, and that’s not something that will change. It will likely become even more popular in a post-Covid world, possibly doing away with ticket lines altogether.

But even if visitors purchase their tickets online, they will still encounter lines and need lobby spaces. Spolidoro imagines sculptural and artistic lobbies, ones that are mostly contained inside an outdoor courtyard, allowing lines to form in the open air. Open-air museums, like those that encompass historical settlements, already have a leg-up on this design aspect. But new museum spaces, like the Studio Museum in Harlem, are incorporating it, too. When Studio's new building is complete in 2021, it will have a “reverse stoop” feature—a staircase where visitors can sit and engage with each other on the way down to a multi-use lobby area with entry doors that fully open up to the sidewalk. LACMA has this feature, as well—when the building design changed 14 years ago, Govan made sure the lobby, ticketing area and some sculpture work were all outside. LACMA even has buildings, like the Zumthor building, designed specifically to cast shade for outdoor events and activities.

“Being outside is always better than being inside in terms of particles spreading around,” Spolidoro says. “But at the same time, in windy conditions, particles can spread. So museums with courtyards could be another design solution that can keep people outside with less wind to spread germs.”

We see them everywhere right now: markings on the floor to denote six-foot distance. They’re made from tape, stickers, stencils, really whatever business owners have on hand to show where customers can safely stand. And that’s not likely to go away in the world of future museum design—it just might get a little bit prettier, Spolidoro says. Future museum floors could have design and architectural elements that mark six feet, like specific tiling patterns or strategically placed carpet squares, or even ridges along the floor at six-foot distances.

“Super sad vinyl sheets … or painter’s tape on the floor, that’s a wartime fix for when you really have to do it,” Spolidoro says. “But when you’re thinking about design, it would be a different, more thoughtful approach on the patterns and the volumes of architecture. Museums could be conceived as a more experiential environment.”

Gift Shops

Future museum designers and architects need a way to stem the almost certain spread of germs and viruses in museum gift shops, where visitors pick up items and set them back on the shelf for others to then touch. Spolidoro’s suggestion? Make the gift shop a museum itself, with a pick-up window. Either display the merchandise throughout the museum, where customers can then order it from their phone without touching the actual item, or have a hands-free gift shop experience where instead of touching the merchandise in the store you order at a pick-up spot. “It’s very meta,” Spolidoro says.

Staffing

Front-of-house museum staff have faced mass layoffs as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, along with tour guides, in-house educators and museum interpreters. Potential changes, like online ticketing and hands-free gift shops, could push some museum workers out of a job once everything reopens fully. Govan says he was lucky—not a single LACMA employee lost their job. But still he, like so many others in the museum world, has had to pivot and rethink what it means to be a museum employee. The pandemic is forcing museums to focus on each individual job and how it can be retooled for the future—whether that means moderating a live panel in an outdoor theater, giving tours to very small groups, or even producing videos or scripted phone calls about the items in a museum's collection. It's also bringing employee health and safety top-of-mind.

“Those ideas are going to stick with us, the level of communication [and] care, safety, making sure sick people aren’t in your environments, the awareness, and also, because of the economic crisis, the care for jobs,” Govan says. “Just thinking carefully about each job and its value and the value of each person employed. The focus on the well-being of employees has been magnified many fold.”

Exhibit Design

The typical exhibition space at art and history museums consists of large open rooms, flanked and filled with display cases or artwork—which, on crowded days, has a dismal effect on social distancing. In order to keep a six-foot distance in mind, exhibits and their layouts will need to be retooled. (For hands-on science museums and children's museums, the logistics of exhibit changes are paralyzingly complex.) Spolidoro suggests using a labyrinthine design concept, where you enter in one place, follow a curated path throughout the exhibit so that you don’t pass the same place twice, and exit at another spot.

That still, though, could leave an issue: text on walls. Govan and his team have been trying to eliminate it for years.

“I’ve wanted to get rid of wall text and wall labels my whole career for various reasons, including the difficulty of eye focus, coming up close, stepping back,” he says. “It’s a real accessibility issue, and also [there's a bad] experience of crowding around wall text and trying to look over people’s shoulders. It’s hard to change the way we work, [but] one of the things that’s happening with Covid is the license to experiment. What we’re going to find from the experimentation—reducing wall texts, spacing works farther apart—is a better experience, which we could have found otherwise, but this is forcing us into trying it out.”

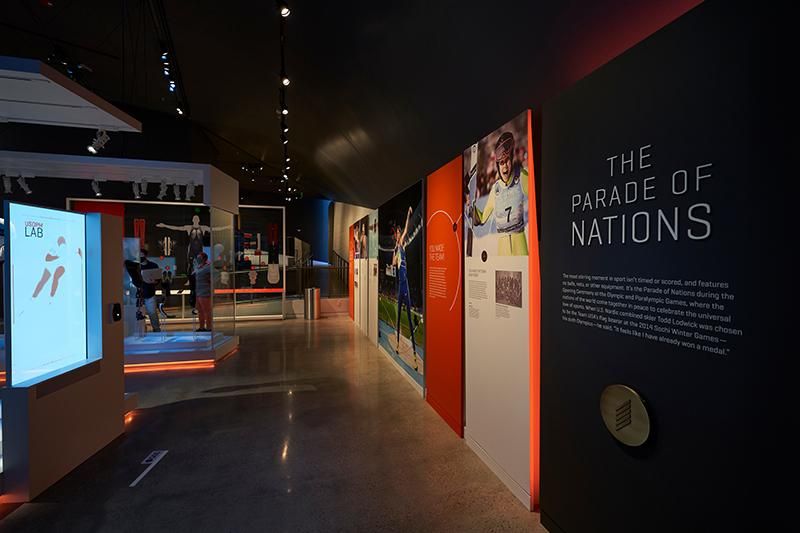

Govan thinks mobile and digital experiences, like phone calls, videos or pamphlets you can experience beforehand to create some context for the exhibits, could replace wall text. Virtual experiences could come into play here, as well. At the new U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Museum in Colorado Springs, one of the main exhibits will be a digital experience of the Parade of Nations. In it, visitors to the museum will walk through a 360-degree immersive experience, allowing them to join Team USA “virtually” as they carry the American flag in the parade.

The SPYSCAPE Museum in New York has also embraced newly virtual experiences for the long-term. The museum unveiled a companion app that allows everything to be touchless, launched a podcast and will debut a new online film festival and culture convention. Another spy-focused institution, the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., recently introduced the ability to rent out the entire museum overnight for small groups (up to 20 people), and has launched virtual spy trivia and interactive family game nights.

Creating an entirely virtual museum is already one approach for the future, but it’s a slippery slope. Museums might be enticed by the idea of having their entire collections online in order to avoid the possible transmission of disease, but then what happens to the buildings?

“It will be a huge loss in terms of the actual experience of seeing the object in the space in front of you or a painting in front of you,” Spolidoro says. “It then means that museums become cemeteries for objects that should actually be lived in the piece of architecture.”

It raises another issue of maintenance costs, as well. With everything online, a museum building would morph into something that’s more or less just storage. And if that happens, people paying for memberships to support the museum could pull back and wonder why they continue to pay for a building to look and feel the same way it did pre-pandemic when no one is able to use it how they did pre-pandemic.

“It is more sustainable for financial purposes to actually live the space and be very connected with these things,” Spolidoro says. She does note, though, that all museums should strive to have a virtual component, especially as explorations into virtual reality continue to move forward. “But,” she cautions, “we cannot pretend to substitute the true experience.”

“You really have to measure what you’re doing by an equity lens too,” Govan says. “Everything can’t be all online. It’s not the only solution.” The idea of going completely online, he adds, brings with it underlying problems with accessibility to the digital medium. “I think what’s going to happen, hopefully, is that Covid is going to create an urgency to fix that problem.”

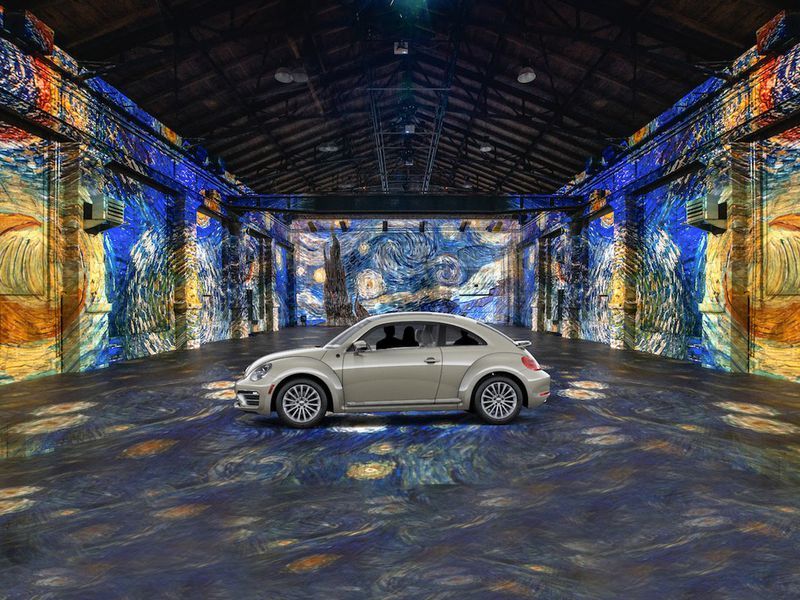

Spolidoro thinks there’s also an opportunity to change the entire concept of a museum. Instead of having a space people walk through, perhaps we could take a cue from banks and movie theaters and create drive-in museums.

“[Only digitizing exhibits] would be a huge loss in terms of the actual experience of seeing an object in the space in front of you,” Spolidoro says. “Could we infuse our cities with pieces of art that you can … drive or walk through?”

A good example is a drive-through Van Gogh exhibit in a 4,000-square-foot warehouse in Toronto, “Gogh by Car,” which opened on July 1. The initial sold-out experience, designed by artist Massimiliano Siccardi and composed by musician Luca Longobardi, allowed guests to drive into a completely immersive projection of Starry Night and Sunflowers, complete with an original soundtrack. Fourteen cars were allowed in at once to the 35-minute show. The first run of the show hasn't officially ended, either; there's a walk-in portion and a drive-in portion, both of which are still in operation. The drive-in portion is running through October 12, and the walk-in portion through November 1. More than 100,000 people have attended the exhibit so far, and it's now become a unique event space as well—most recently, hosting social distant fitness classes. Eventually, the building will be turned into condos. SPYSCAPE has also embraced the museum-through-the-city concept with a new mobile game that allows players to use a Pokémon Go-style platform to test secret spy skills throughout their neighborhood and town.

“Gogh by Car” and SPYSCAPE's game are groundbreaking, both for the immersive experience, and also for accessibility of museum collections in general.

“Viewing art from inside a car provides a safe experience for people who are physically fragile, fearful of the virus or vulnerable,” Corey Ross, a co-producer of the exhibit, told the Hindustan Times. “The feeling is unique, almost as if the car is floating through the art.”

Drive-By-Art exhibits in Long Island and Los Angeles, mural shows and outdoor walking exhibits throughout major cities are setting the wheels in motion for a more inclusive opportunity to view museum collections.

“I think there is going to be a lot more thinking about the outdoors and museums for that reason,” Govan says.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)