The Story Behind Che’s Iconic Photo

Fashion photographer Alberto Korda took Che Guevara’s pictures hundreds of times in the 1960s. One stuck

:focal(1526x1654:1527x1655)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/46/66461d4d-a1e8-494a-871b-2d557d815f2d/chehigh.jpg)

My grandmother used to light a candle to worship him, even though her idol had been an atheist throughout his life. The memory still dances in quivering light: When I was a child in the late ’70s in Havana, during the never-ending blackouts, I was terrified by the shadows on his face.

That famous face, printed on a huge poster my grandmother had scavenged from the streets of Havana following a military parade: It was heroic, seemingly immortal, and yet a decade had passed since he’d been killed in the jungles of Bolivia, a country I couldn’t have pointed to on a map.

Grandma used to pray to him as “Saint Che.” She wasn’t fond of the revolution, but she did believe in strong spirits that refuse to leave this world. For years I thought that his family name was Sánchez (which Cubans pronounce SAHN-che), and that Che was a diminutive. Then in school I learned that he was Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, and that he’d been given pop culture immortality by a former fashion photographer named Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez, who’d later changed his name to Korda. Everything about the man and the myth was always a little off-kilter.

The photo, so prominent in the shadowy world of my childhood, became one of the most reproduced images ever, rivaling those of the “Mona Lisa” and Marilyn Monroe with her skirts flying. It was Che as deity—and went viral long before the advent of YouTube, Twitter, Snapchat, and Facebook. From Bolivia to the Congo, from Vietnam to South Africa, from the U.S.S.R. to the U.S.A., Korda’s Che became the apostle of anticapitalism and the ultimate icon for peaceful social activists everywhere—despite the fact that Che himself had preached hatred as a tool for the “New Man” to wipe exploitation from the Earth.

How his mug made the rounds! To the student barricades of Paris, 1968. To the album cover of Madonna’s American Life. To Jim Fitzpatrick’s psychedelic posters. To Jean-Paul Gaultier’s sunglasses. From cigar boxes to condoms, from Che Christ to gay-pride Che, from dorm room to dorm room and refugee camp to refugee camp. To the facade of the frightening Ministry of the Interior in Havana’s Plaza of the Revolution.

The iconic Che was nothing if not adaptable. Patrick Symmes, who tried to disentangle the man from the myth in his book Chasing Che: A Motorcycle Journey in Search of the Guevara Legend, told a New York Times reporter, “I think the more that time goes by, the chicer and chicer Che gets because the less he stands for anything.”

**********

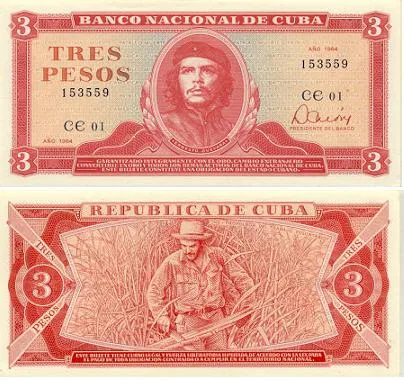

Che was not Cuban. But in February 1959 he was granted Cuban nationality “by birth.” Che was not an economist. But by November of that same year he was president of the Cuban National Bank, where he signed the currency with his three-letter nom de guerre. Che wasn’t even very handsome, his features puffy after a lifelong battle with asthma. But he’s remembered as the most photogenic idol of the Cuban Revolution and beyond.

For Cubans, and not only those of my generation, Korda’s Che is less about guerrilla chic and more about a mix of superstition and socialism, ideology and ignorance, fidelity and fear. Many venerate his absence as a symbol of what the revolution was meant to be, maybe because the man himself would be too overwhelming for us today, when the shopping mall is far more central to our lives than Marxist manifestos.

We might still need heroes, yes, but not heroes so powerful as to lead us like sheep to some faraway paradise. Who were we following anyway?

In this era of anything-goes globalization, Che doesn’t really stand for anything partly because he stands for so much. Once a symbol of a society struggling toward the ultimate abolishment of money—during the 1960s at least three communal experiments were launched in the Cuban countryside to achieve this goal—Korda’s Che has now been converted into its own form of capitalist currency: a cool knickknack or keepsake, a pin or poster or touristy T-shirt. When the Rolling Stones performed in Havana’s Sports City this year (provocatively, on Good Friday), Korda’s Che welcomed “their satanic majesties” from the audience in his usual heroic form, except for the big, fat, redder-than-ever Rolling Stone tongue protruding from his mouth. And you can bet that tongue came thanks to a pirated copy of Adobe Photoshop.

Cubans who can’t make a decent living in their own professions—including doctors and engineers trying to survive on the low salaries paid by the state—have learned how to make and sell Che trinkets. They hawk them in tourist markets, in accordance with new government regulations that allow selling to occur por cuenta propia (literal translation: “by individual account”)—but only after fees and taxes have been extracted.

Nowadays, when Cuban government functionaries mention Che at all, they tend to repetitively quote a couple of common phrases—“the highest level of the human species is being a revolutionary” or “the true revolutionary is guided by big feelings of love”—and they keep a large picture of him in their offices as an emblem of their ideological purity. But those types are increasingly rare, and they’re mostly pretenders who know very little about Che’s life and thoughts.

Even Frank Delgado, a Havana troubadour who sincerely admires Che’s epoch, condemns what he sees as the revolutionary decadence of today:

Those who use your image as the topic of their sermons

While doing the opposite of what they teach

We won’t allow them further speeches honoring you

Nor the use of your image if they preach what they are not.

Curiously enough, Korda’s Che, at least as ubiquitous in Cuba as in the rest of the world, came to be published by chance. The photo started as a reject, a casually captured news image that a Cuban newspaper didn’t publish. It was used initially to decorate Korda’s studio.

**********

On Friday, March 4, 1960, a ship exploded in Havana Harbor, killing more than a hundred workers and injuring many more, including passersby who rushed to offer help. It was the vessel La Coubre, loaded with tons of weapons bought in Belgium by the Cuban government and secretly transported to the Caribbean.

The details are sketchy, but it seems the arms and ammunition may have been off-loaded by ordinary dockworkers to disguise the operation from the “enemies of the people”—local opposition groups, exiled “counterrevolutionaries,” and CIA officers who kept a close eye on Fidel Castro.

Alberto Díaz Gutiérrez, a staff photographer for the newspaper Revolución, was assigned to cover the funerals the next day at the Colón Cemetery. Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, enchanted with a tropical utopia that might lend color to the gray Stalinism of Soviet-style communism, were among the honored guests. Close to them stood Che, who years earlier had signed letters to his family as “Stalin II,” swearing to an aunt “before a stamp of the old and mourned comrade Stalin” that he wouldn’t “rest until seeing these capitalist octopuses annihilated.”

In Castro’s funeral oration, as might be expected during the not-so-Cold War, he announced that the explosion had been sabotage. He went on to accuse the U.S. of the crime, the only evidence being his own monologue to the masses (typical of what he called “direct democracy”). It was on that Saturday that he first uttered his slogan “Homeland or Death,” radically transforming Cuba’s republican- era motto “Homeland and Liberty.”

Díaz was by then better known simply as Korda, but it wasn’t a nom de guerre. Before the revolution, which began in 1956, he and his friend Luis Antonio Pierce had named their studio Korda after two Hungarian film directors. They took on the name of their Hungarian idols and worked as fashion photographers who made the most of Cuba’s natural light to commercialize clothes and promote TV stars.

But in 1959 Castro’s revolution turned them into graphic reporters committed to a cause. Private businesses were being forcibly nationalized, and the two men grasped that the rebeldes were fast becoming the only lawful employer and trademark left.

Korda would later recall his magic Che shutter click: “At the foot of a podium decorated in mourning, I had my eye to the viewfinder of my old Leica camera. I was focusing on Fidel and the people around him. Suddenly, through the 90mm lens, Che emerged above me. I was surprised by his gaze. By sheer reflex I shot twice, horizontal and vertical. I didn’t have time to take a third photo, as Che stepped back discreetly into the second row…. It all happened in half a minute.”

Back home, Korda cropped the horizontal shot into a vertical portrait, because in the full frame another man was emerging near Che’s right shoulder and some palm branches hung over him on the left. The Revolución editors declined the black-and-white print without further comment. They simply preferred to run one of Korda’s pictures of the commander in chief, and another picture of Castro’s philosopher guests Sartre and Beauvoir.

Korda hung the Che image in his apartment. He used to call it “Guerrillero Heroico,” and he liked to describe the Che who appeared in it as a human being who was encabronado y doliente (pissed off and pained), with “impressive force in his expression, given the anger concentrated in his gaze after so many deaths.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/2a/902a52bb-a99c-43a4-a96a-27676723a005/heroico1.jpg)

**********

Despite having taken hundreds of pictures of Che, Korda insisted that the Argentine Cuban didn’t like to be photographed. For Che was obsessed with neither governance nor diplomacy but with exporting the revolution by any means—a mission too sacred for him to play a character who emerges for half a minute and then steps back discreetly behind the verbosity of Fidel Castro. He was a man of action and needed to get back to it.

In 1965 the Cuban people heard nothing of their supposed hero for six months, until Castro unexpectedly made public a farewell message from his old comrade. In the letter, Che renounced all of his civil and military positions—including his Cuban nationality—because, as he said, “other regions of the world claim the support of my modest efforts.”

Though Korda and Che had been born just months apart in 1928, the photographer would outlive his subject by more than 33 years. Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was executed by U.S.-trained soldiers in Bolivia in 1967, after being captured with help from a Cuban exile working for the CIA.

A couple of months before Che’s death, Italian businessman Giangiacomo Feltrinelli knocked on Korda’s door in Havana. He’d arrived in Cuba directly from Bolivia and handed Korda a letter from Haydée Santamaría, then president of Casa de las Américas— a cultural think tank that was helping to export the ideology of the Cuban Revolution—requesting that he provide Feltrinelli a good picture of Che.

Korda pointed to his studio wall, where the picture passed over by Revolución—a newspaper which no longer existed—was still hanging. “This is my best picture of Che,” he said.

Feltrinelli asked for two copies, and the next day Korda made two eight-by-ten prints. When asked about the price, Korda said the photos were a gift because Feltrinelli had been sent by someone he regarded highly. That may well be true, but accepting money in payment could also have been risky. The government was on its way to extinguishing all private business, and possession of foreign currency was a crime that carried a prison sentence. (That restriction continued until the “dollarization” decree of 1993, after decades of generous Soviet subsidies ended and Fidel Castro took to the airwaves to personally approve the use of American dollars in special Cuban stores, officially named hard-currency-collection stores.)

Heir to one of Italy’s wealthiest families, Feltrinelli had turned his considerable energy to radical, left-wing causes. With Che’s corpse barely cold in Bolivia, he began selling millions of posters that used Korda’s photo but made no mention of the Cuban photographer. When Fidel Castro handed him a copy of Che’s diary from the Bolivian jungle, Feltrinelli published that too, with Korda’s unsigned picture on the cover.

According to his son, Carlo, Feltrinelli baptized Korda’s masterpiece “Che in the Sky With Jacket,” a riff on “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.” It’s an irony within an irony that Beatles songs were censored in Cuba at the time and that rock-and-roll lovers, considered “extravagant beings,” were being rounded up, along with homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and nonconformist hippies. They were sent off to forced-labor camps under the infamous program UMAP—Military Units in Aid of Production. These were prisons in the countryside where inmates were to be “turned into men” by hard work—a kind of aversion therapy that could have inspired Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange—and held without charges until their behavior, at least to all appearances, was deemed proper for members of the “dictatorship of the proletarians and farmers.”

The violence that runs through this story did not spare Feltrinelli. In 1972, the man who helped smuggle Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago out of the Soviet Union in the ’50s was found dead near Milan, apparently killed by his own explosives, next to a high-voltage power line he was suspected of attempting to sabotage. Suspicions of suicide and assassination still surround his death. The Soviets never forgave him for helping Pasternak, just as they never forgave Che for being an admirer of Mao, whose global aspirations conflicted with their own.

**********

For decades Korda never earned a cent from the broad distribution of his iconic picture. Such profiting would have been unrevolutionary. “The strange thing is that air cannot be shut up in a bottle, but something as abstract as intellectual property can be shut up,” declared Castro in 1967. Asking “Who pays Shakespeare? Who pays Cervantes?” he concluded that Cuba had “de facto adopted the decision to also abolish intellectual property.” And so, de facto, Korda’s Che had to be given away for free.

Just before his death, Korda did file and prevail in some legal claims and finally had his copyright confirmed by the London High Court. He was then able to stop the use of his Che image in Smirnoff vodka ads, arguing that he considered such commercial exploitation an insult to the legacy of the guerrillero heroico. (Korda insisted to the press that neither he nor his hero ever drank alcohol.) He received $50,000 from the settlement, which he donated to the Cuban state to buy children’s medicine on the international market.

Yet capitalism is a force that’s hard to resist. Korda’s Che did end up on Cuba’s three-peso bill, which is approximately equivalent to an American dime. And now Cuba is on its way to becoming a state-controlled market economy, engaging with “imperialism” even before what some call the “Castrozoic era” ends.

For the time being, Korda’s Che still frowns from the facade of Cuba’s mysterious Ministry of the Interior—where repression is ordered and reality staged. And his image continues to be framed into the last selfies of socialism by tourists passing through what was once called Civic Square and is now the Plaza of the Revolution. Even Barack Obama, during his visit in March 2016, paused with American and Cuban officials for a group photo with Korda’s Che in the background. Maybe he saw the irony or some political utility in the shot. Still, it was more evidence—as if any were needed—that the magic somehow persists.

Meanwhile, the mortal remains of Ernesto Guevara de la Serna, their authenticity subject to ongoing debate, are kept as a communist totem in Santa Clara, in the geographical center of Cuba— a withering testament to one of the last attempts to create a utopia on Earth. “Hasta la victoria siempre”—toward victory always—used to be Che’s war mantra, even if the price would be intolerable and the victory unattainable. In the end, it seems, Korda’s Che remains the guerrillero heroico— eternally pissed off and pained.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.