In Kyoto, Feeling Forever Foreign

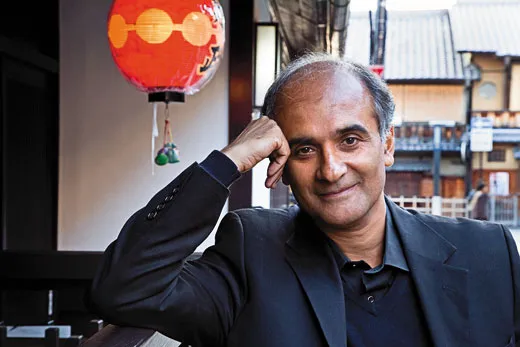

Travel writer Pico Iyer remains both fascinated and puzzled by the ancient Japanese city

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/My-Town-Kyoto-Japan-geisha-district-631.jpg)

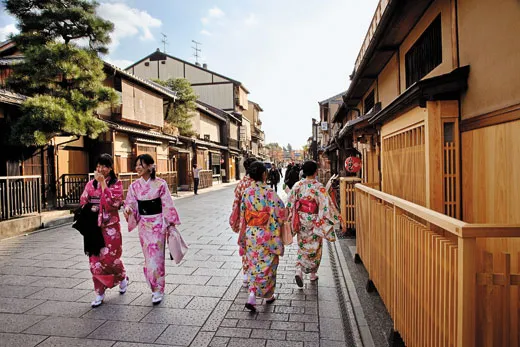

It was a little more than 25 years ago that I first walked the streets of Gion, the centuries-old geisha district of Kyoto. I was jet-lagged—just off the plane from California on my way to India—and everything seemed alien: the signs were in four separate alphabets, people read books from right to left (and back to front) and most, I heard, took baths at night. Yet something got through to me as I walked the streets under the shadow of the ancient capital’s eastern hills, saw pairs of slippers neatly lined up at restaurant entrances and heard, through an upstairs window, the bare, plaintive sound of a plucked koto. So much in this historic Japanese city stirred the imagination: Nijo Castle with its squeaking floorboards—to warn shoguns of intruders; the thousands of red torii gates at Fushimi Inari Shrine that led up a wooded hillside of stone foxes and graves.

Residents inevitably see things differently than visitors. But nowhere are the perceptions more disparate than in Japan. After 22 years of living here, I’m still known as a gaijin (outsider or foreigner) and generally feel as if I’m stumbling through the city’s exquisite surfaces like a bull in an Imari china shop. But as I walk down the narrow, lanterned lanes today, the city has an even richer and more intimate power than when I first wandered them as a dazzled sightseer.

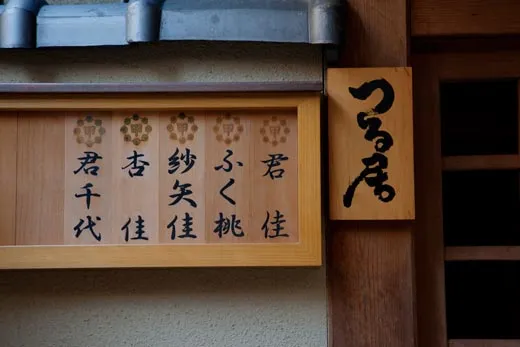

I now know that the little wooden buildings that first looked so rich in mystery are geisha houses, or boardinghouses for mistresses of the classical arts, designated by black vertical plaques at their entrances; the blond wood signs above them denote the names of maiko (apprentice geishas) who live inside. The latticed windows on these and nearby houses allow a kind of espionage—residents can see out without being seen—and the narrow entrances to large homes were designed to thwart the tax collector, whose rates were once based on a house’s width at the street. The white herons perched on the central river’s concrete embankments were not even here when my Kyoto-born wife (whom I met in a temple my first month in the city) was young. “They’ve come back because the river has been cleaned up,” she tells me. The very name of the waterway, Kamogawa, so mellifluous and elegant, I now know means “Duck River,” bringing the woozy romance down to earth.

If you turn to any guidebook, you will see that Kyoto, which is surrounded on three sides by hills, became Japan’s capital in 794. It remained so until the Meiji government shifted the capital to Tokyo in 1868. For more than a millennium, therefore, almost everything we associate with classical Japanese culture—kimonos, tea ceremonies, Zen temples and, yes, geisha—came to its fullest flowering and refinement in Kyoto. It’s as if the historical attractions of Colonial Williamsburg, Boston and Washington, D.C. were combined in a single city; this is where scores of emperors, as well as courtesans, samurai and haiku-writing priests, made their homes.

To this day, roughly 50 million pilgrims come every year to Kyoto to pay homage to what one might think of as a citywide shrine to Japaneseness. The “City of Peace and Tranquility,” home to some 2,000 Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines, boasts 17 Unesco World Heritage sites and three imperial palaces. But living here, you learn that the bustling modern city of 1.4 million people was also, at the turn of the last century, the site of Japan’s first streetcars, first water-power station and first film projection. (By the 1930s, its movie studios were producing more than 500 films a year.) Indeed, Kyoto has managed not only to preserve old grace notes but also continually to generate new ones. That revolutionary video-game system Wii, which arrived a few years ago to trump Sony and Microsoft? It’s from Nintendo, the Kyoto-based company known for its playing cards more than a century ago. Kumi Koda, the blond, micro-skirted pop idol once known as the Britney Spears of Japan? She’s from Kyoto too. As is Japan’s leading novelist, Haruki Murakami, renowned for his tales of drift and his references to Western music and pop culture. Part of his most famous novel, Norwegian Wood, is set in the mountains near the city.

When I decided to move to Kyoto in 1987, three years after my initial trip—leaving behind a job in Midtown Manhattan writing about world affairs for Time magazine—I found a little temple on a tiny lane near the Gion geisha district, and, wanting to learn about simplicity and silence, resolved to live there for a year. Settling into a bare cell, I quickly learned that temples are big business (especially in Kyoto), as full of hierarchy and ritual as any Japanese company, requiring a lot of hard work and upkeep—not just dreamy contemplation. I soon moved to a little guesthouse near the Buddhist temples of Nanzenji and Eikando in the northeastern part of town and resumed my Japanese education by observing how passionately my neighbors followed the Hanshin Tigers baseball team, marked the harvest moon by devouring “moon-viewing burgers” at McDonald’s and, in spring, celebrated the season by smoking cigarettes with cherry blossoms on the packages. It was not a temple’s charms I’d been seeking, I quickly realized, but Japan itself—and to this day I spend every autumn and spring here.

As the years have gone by, Kyoto, like any lifelong partner, has changed—from bewitching mystery to a beguiling fascination that I can never hope entirely to understand. Still, I have managed to slip past a few of the veils that keep the city so seductive; I now mark the end of summer by the smell of sweet olive trees in late September and can tell the time of day from the light coming through my gray curtains. I know to go to the seventh floor of the BAL department store for the latest John le Carré novel and to savor chai at Didis, a little Nepali café just north of Kyoto University. My own memories are superimposed over the official map of the city: this is where I saw the topknotted sumo wrestler on his way to a nightclub, and here is the art-house cinema (near an eighth-century pagoda) where I caught Martin Scorsese’s movie about Bob Dylan.

Among a thousand other things, Kyoto is a university town, which means that its ancient streets remain forever young; many bustle with things I’d never have noticed (or wanted to see) as a visitor—surfers’ restaurants offering “Spam Loco Moco,” “live houses” for punk rock bands, shops selling Ganeshas or Balinese sarongs. “I could never live in Kyoto,” an old Nagasaki friend told me recently. “It’s too full of its own traditions, its own customs. But if I were talking to a young person, I’d tell her to go to university in Kyoto. It’s funkier, fresher and more fun than Tokyo.”

Indeed, in seeking out the old, as I did when I first came here, I would have never guessed that Kyoto’s real gift is for finding new ways of keeping up its ancient appearances. It’s constantly maintaining its traditional character, even in the midst of the fluorescent pinball arcades, fashion emporia and minimalist bars that turn parts of it into a 23rd-century futuristic outpost. More and more wooden buildings in the center of town (once bulldozed to make way for high-rises) are reopening their doors as chic Italian restaurants or design studios; temples have begun pulling back their gates after dark for “light-up” shows, displays of illuminated grounds that at once accentuate their shoji screens and bamboo forests and smuggle a touch of Las Vegas into centuries-old rock gardens. Platinum blond Japanese teenagers now pay $100 or more to get made up as apprentice geisha, with the result that there are ever more whitened faces clacking through the old streets on wooden sandals; “tradition” is in such demand that more and more weathered-looking teahouses are opening up along the hills. It took me a long while to realize that a truly sophisticated courtesan (which is how I think of Kyoto) keeps changing in order to remain ahead of the times.

Not long ago, I visited, for the first time, a gleaming, 11-story glass tower in the center of Kyoto—home to the classic Ikenobo flower arrangement school. I browsed among the baskets and special scissors and spiked holders in the Ikenobo store, then, exiting the building through a different door than the one I entered, found myself in a serene little courtyard around a hex-ago-n-al wooden temple. Thirty-five elderly pilgrims dressed all in white were chanting outside the temple’s entrance. The smell of incense sharpened the air. In a nearby pond, two swans spread their wings.

Through a little doorway in the square, I found—to my amazement—a Starbucks counter. Single chairs had been set out in a straight line so that latte drinkers, instead of chatting, could just look out upon the temple. Soft piano music turned the area even more distinctly into a meditation zone. The English Breakfast tea I bought there tasted just the same as if I’d bought it at Los Angeles International Airport. But drinking it in that tranquil setting told me that I was in a very different country now, and one that I could almost call my own.

Pico Iyer’s most recent book is The Open Road, about the Dalai Lama.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.