In Sicily, Defying the Mafia

Fed up with extortion and violent crime, ordinary citizens are rising up against organized crime

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Godfather-Sicily-fiaccolata-631.jpg)

Until recently, Ernesto Bisanti could not have imagined he would face down the Cosa Nostra (Our Thing)—the Sicilian Mafia. In 1986 Bisanti started a furniture factory in Palermo. Soon after, a man he recognized as one of the neighborhood’s Mafiosi visited him. The man demanded the equivalent of about $6,000 a year, Bisanti told me, “ ‘to keep things quiet. It will be cheaper for you than hiring a security guard.’ Then he added, ‘I don’t want to see you every month, so I will come every June and December, and you will give me $3,000 each time.’ ” Bisanti accepted the deal—as had nearly all the shop and business owners in the city.

The arrangement lasted for two decades. “Sometimes he showed up with a son in tow,” Bisanti recalled, “and he would say, ‘Please tell my son that he has to study, because it’s important.’ It became like a relationship.” A stocky man with gray hair, Bisanti, 64, told me the money wasn’t that burdensome. “In their system, it’s not important how much you pay. It’s important that you pay,” he said. “It’s a form of submission.”

Then, in November 2007, police arrested Salvatore Lo Piccolo, the head of Palermo’s Mafia. A notebook found in Lo Piccolo’s possession contained a list of hundreds of shop and business owners who paid the pizzo—an ancient word of Sicilian origin meaning protection money. Bisanti’s name was on the list. The Palermo police asked him if he would testify against the extortionist. Not long ago, such a public denunciation would have meant a death sentence, but in recent years police raids and betrayals by informers have weakened the Mafia here, and a new citizens group called Addiopizzo (Goodbye Pizzo) has organized resistance to the protection rackets. Bisanti said yes, took the witness stand in a Palermo courtroom in January 2008 and helped send the extortionist to prison for eight years. The Mafia hasn’t bothered Bisanti since. “They know that I will denounce them again, so they are fearful,” he said.

This sun-drenched island at the foot of the Italian peninsula has always been a place of conflicting identities. There is the romantic Sicily, celebrated for its fragrant citrus groves, stark granite mountains and glorious ruins left by a succession of conquerors. The vast acropolis of Selinunte, built around 630 B.C., and the Valley of the Temples at Agrigento—described by the Greek poet Pindar as “the most beautiful city of the mortals”—are considered among the finest vestiges of classical Greece, which ruled Sicily from the eighth to the third centuries B.C. In the ninth century A.D., Arab conquerors built frescoed palaces in Palermo and Catania; few churches are more magnificent than Palermo’s Palantine Chapel, erected from 1130 to 1140 by Sicily’s King Roger II during a period of Norman domination. Natural splendors abound as well: at the eastern end of the island rises Mount Etna, an 11,000-foot-high active volcano, beneath which, according to Greek mythology, lies the serpentine monster Typhon, trapped and entombed for eternity by Zeus.

But Sicily is also known as the birthplace of the Mafia, arguably the most powerful and organized crime syndicate in the world. The term, which may derive from the adjective mafiusu—roughly “swaggering” or “bold”—gained currency in the 1860s, around the time of Giuseppe Garibaldi’s unification of Italy. It refers to the organized crime entrenched in Sicily’s then-isolated, largely rural society. When Allied forces invaded Sicily during World War II, they sought help from Italian-American mobsters with Sicilian ties, such as Vito Genovese, to secure control of the island. The Allies even allowed Mafia figures to become mayors there. Over the next few decades, the Cosa Nostra built relationships with Italian politicians—including Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti (who served seven terms between 1972 and 1992)—and raked in billions through heroin trafficking, extortion, rigged construction contracts and other illegal enterprises. Those who dared speak out were usually silenced with a car bomb or a hail of bullets. Some of the most violent and consequential Mafia figures came from Corleone, the mountain town south of Palermo and the name novelist Mario Puzo conferred on the American Mafia family central to his 1969 novel, The Godfather.

Then, in the 1980s, two courageous prosecutors (known in Italy as investigating magistrates), Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, using wiretapping and other means, persuaded several high-ranking mobsters to break the oath of silence, or omerta. Their efforts culminated in the “maxi- trial” of 1986-87, which exposed hidden links between mobsters and government officials, and sent more than 300 Cosa Nostra figures to prison. The Mafia struck back. On May 23, 1992, along the Palermo airport highway, hit men blew up an armored limousine carrying Falcone, 53, and his magistrate-wife Francesca Morvillo, 46, killing them and three police escorts. Borsellino, 52, was killed by another bomb, along with his five bodyguards, as he walked to his mother’s Palermo doorway less than two months later.

But rather than crippling the anti-Mafia movement, the assassinations—as well as subsequent Mafia car bombings in Milan, Florence and Rome that killed a dozen people—galvanized the opposition. In January 1993, Salvatore (“The Beast”) Riina, the Cosa Nostra’s capo di tutti i capi, or boss of all bosses, from Corleone, who had masterminded the assassinations, was captured near his Palermo villa after two decades on the run. He was tried and sentenced to 12 consecutive life terms. Riina was succeeded by Bernardo (“The Tractor”) Provenzano, who shifted to a low-key approach, eliminating most violence while continuing to rake in cash through protection rackets and the procurement of public building contracts. In April 2006, police finally tracked down Provenzano and arrested him in a crude cottage in the hills above Corleone; he had been a fugitive for 43 years. Provenzano went to prison to serve several consecutive life sentences. His likely successor, Matteo Messina Denaro, has also been on the run since 1993.

Even before Provenzano’s arrest, a quiet revolution had begun to take hold in Sicilian society. Hundreds of businesspeople and shopkeepers in Palermo and other Sicilian towns and cities began refusing to pay the pizzo. Mayors, journalists and other public figures who once looked the other way started speaking out against the Mafia’s activities. A law passed by the Italian parliament in 1996 allowed the government to confiscate the possessions of convicted Mafia figures and turn them over, gratis, to socially responsible organizations. In the past few years, agricultural cooperatives and other groups have taken over mobsters’ villas and fields, converting them into community centers, inns and organic farms. “We’ve helped local people change their views about the Mafia,” says Francesco Galante, communications director of Libera Terra, an umbrella organization led by an Italian priest that today controls nearly 2,000 acres of confiscated farmland, mainly around Corleone. The group has created jobs for 100 local workers, some of whom once depended on the Cosa Nostra; replanted long-abandoned fields with grapes, tomatoes, chickpeas and other crops; and sells its own brands of wine, olive oil and pasta throughout Italy. “The locals don’t see the Mafia anymore as the only institution they can trust,” Galante says.

After I landed at Palermo’s Falcone-Borsellino Airport this past March—renamed in 1995 in honor of the murdered magistrates—I rented a car and followed the Mediterranean seacoast toward Palermo, passing Capaci, where Falcone and his wife had met their deaths. (A Mafia hit team disguised as a construction crew had buried half a ton of plastic explosives inside a drain pipe on the airport highway and detonated it as Falcone’s vehicle crossed over.) After turning off the highway, I drove past row after row of shoddily constructed concrete apartment blocks on Palermo’s outskirts, an urban eyesore built by Mafia-controlled companies in the 1960s and ’70s. “This is Ciancimino’s legacy,” my translator, Andrea Cottone, told me as we drove down Via della Libertà, a once-elegant avenue where the tenements have crowded out a few surviving 18th- and 19th-century villas. Billions of dollars in contracts were doled out to the Cosa Nostra by the city’s corrupt assessor for public works, Vito Ciancimino; he died under house arrest in Rome in 2002 after being convicted of aiding the Mafia.

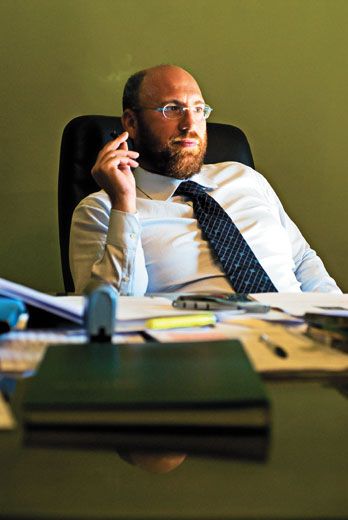

Passing a gantlet of bodyguards inside Palermo’s modern Palace of Justice, I entered the second-floor office of Ignazio De Francisci. The 58-year-old magistrate served as Falcone’s deputy between 1985 and 1989, before Falcone became a top assistant to Italy’s minister of justice in Rome. “Falcone was like Christopher Columbus. He was the one who opened the way for everyone else,” De Francisci told me. “He broke new ground. The effect he had was tremendous.” Falcone had energized the prosecution force and put in place a witness-protection program that encouraged many Mafiosi to become pentiti, or collaborators, with the justice system. Gazing at a photograph of the murdered magistrate on the wall behind his desk, he turned silent. “I often think about him, and wish that he were still at my shoulder,” De Francisci finally said.

Eighteen years after Falcone’s assassination, the pressure on the Mafia hasn’t let up: De Francisci had just presided over a months-long investigation that led to the arrests of 26 top Mafiosi in Palermo and several U.S. cities, on charges from drug trafficking to money laundering. The day before, police had captured Giuseppe Liga, 60, an architect and allegedly one of the most powerful figures in Palermo’s Mafia. Liga’s ascent illustrates the Mob’s transformation: power has shifted from coldblooded killers such as Riina and Provenzano to financial types and professionals who lack both the street smarts—and appetite for violence—of their predecessors. De Francisci described the Addiopizzo movement as the most inspiring symbol of the new fearlessness among the population. “It is a revolutionary development,” he said.

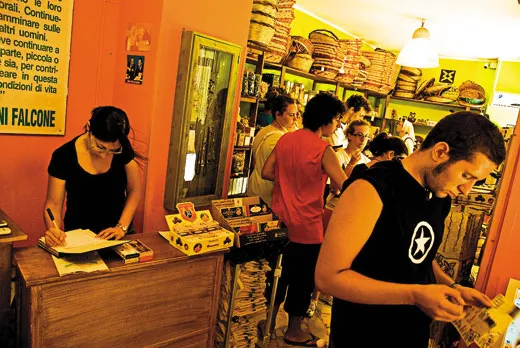

At dusk, I ventured out to Viale Strasburgo, a busy commercial thoroughfare where Addiopizzo had organized a recruitment drive. A dozen young men and women had gathered inside a tent festooned with banners proclaiming, in Italian, “We Can Do It!” Addiopizzo began in 2004, when six friends who wanted to open a pub—and who sensed the Mafia’s weakness—put up posters across the city that accused Sicilians of surrendering their dignity to the criminal organization. “People said, ‘What is this?’ For a Sicilian [the accusation] was the ultimate insult,” Enrico Colajanni, one of the first members told me. The movement now lists 461 members; in 2007, an offshoot, Libero Futuro, was formed; its 100 or so members have testified against extortionists in 27 separate trials. “It’s a good start,” Colajanni said, “but thousands are still paying in Palermo; we need a long time to develop a mass movement.”

According to a University of Palermo study published in 2008, around 80 percent of Palermo businesses still pay the pizzo, and the protection racket in Sicily brings the Mafia at least a billion euros annually (more than $1.26 billion at today’s exchange rate). A handful of attacks on pizzo resisters continues to frighten the population: in 2007, Rodolfo Guajana, an Addiopizzo member who owns a multimillion-dollar hardware business, received a bottle half-filled with gasoline and containing a submerged lighter. He paid it no mind; four months later, his warehouse was burned to the ground. For the most part, however, “the Mafia ignores us,” Addiopizzo volunteer Carlo Tomaselli told me. “We are like small fish to them.”

One morning, my translator, Andrea, and I drove with Francesco Galante through the Jato Valley, south of Palermo, to get a look at Libera Terra’s newest project. We parked our car on a country road and hiked along a muddy trail through the hills, a chill wind in our faces. Below, checkerboard fields of wheat and chickpeas extended toward jagged, bald-faced peaks. In the distance I could see the village of San Cipirello, its orange-tile-roofed houses clustered around a soaring cathedral. Soon we came to rows of grape vines tied around wooden posts, tended by four men wearing blue vests bearing Libera Terra logos. “Years ago, this was a vineyard owned by the Brusca crime family, but it had fallen into disrepair,” Galante told me. A cooperative affiliated with Libera Terra acquired the seized land from a consortium of municipalities in 2007, but struggled to find willing workers. “It was a taboo to put foot on this land—the land of the Boss. But the first ones were hired, and slowly they started to come.” Galante expects the fields to produce 42 tons of grapes in its first harvest, enough for 30,000 bottles of red wine for sale under the Centopassi label—a reference to a movie about a slain anti-Mafia activist. I walked through neat rows of vines, still awaiting the first fruit of the season, and spoke to one of the workers, Franco Sottile, 52, who comes from nearby Corleone. He told me that he was now earning 50 percent more than he did when he worked on land owned by Mafia bosses, and for the first time, enjoyed a measure of job security. “At the beginning, I thought there might be problems [working here],” he told me. “But now we understand that there is nothing to fear.”

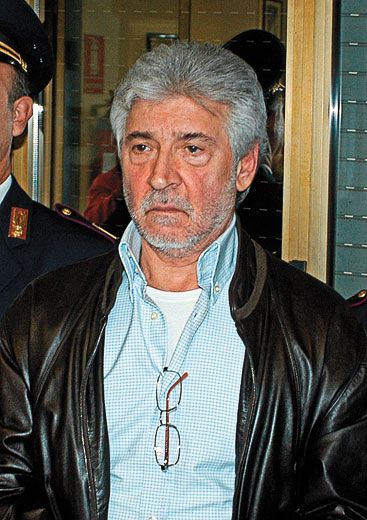

I had heard that the Mafia was less forgiving in Partinico, a gritty town of 30,000 people 20 miles to the northwest. I drove there and parked in front of the main piazza, where old men wearing black berets and threadbare suits sat in the sun on benches surrounding a 16th-century Gothic church. A battered Fiat pulled up, and a slight, nattily dressed figure stepped out: Pino Maniaci, 57, owner and chief reporter for Telejato, a tiny Partinico-based TV station. Maniaci had declared war on the local Mafia—and paid dearly for doing so.

A former businessman, Maniaci took over the failing enterprise from the Italian Communist Party in 1999. “I made a bet with myself that I could rescue the station,” he told me, lighting a cigarette as we walked from the piazza through narrow lanes toward his studio. At the time, the city was in the midst of a war between rival Mafia families. Unlike in Palermo, the violence here has never let up: eight people have been killed in feuds in just the past two years. The town’s key position between the provinces of Trapani and Palermo has made it a continual battleground. For two years, Maniaci aired exposés about a mob-owned distillery in Partinico that was violating Sicily’s antipollution statutes and pouring toxic fumes into the atmosphere. At one point he chained himself to the distillery’s security fence in an effort to get police to shut it down. (It closed in 2005 but reopened last year after a legal battle.) He identified a house used by Bernard Provenzano and local Mafia chieftains to plan killings and other crimes: authorities confiscated it and knocked it down. In 2006 he got the scoop of a lifetime, joining police as they raided a tin shack near Corleone and captured Provenzano. The Mafia has burned Maniaci’s car twice and repeatedly threatened to kill him; in 2008 a pair of hoodlums beat him outside his office. Maniaci went on the air the next day with a bruised face and denounced his attackers. After the beating, he declined an offer of round-the-clock police protection, saying it would make it impossible for him to meet his “secret sources.”

Maniaci led me up a narrow flight of stairs to his second-floor studio, its walls covered by caricatures and framed newspaper clips heralding his journalistic feats. He flopped down in a chair at a computer and fired up another cigarette. (He smokes three packs a day.) Then he began working the phones in advance of his 90-minute, live daily news broadcast. He was attempting to ferret out the identities of those responsible for torching the cars of two prominent local businessmen the night before. Leaping out of his chair, Maniaci thrust a news script into my hands and asked me to read it on the air—despite my rudimentary Italian. “You can do it!” he encouraged. Maniaci often asks visiting foreign reporters to join him on camera in the belief the appearances will showcase his international clout and thereby protect him from further Mafia attacks.

Telejato, which reaches 180,000 viewers in 25 communities, is a family operation: Maniaci’s wife, Patrizia, 44, works as the station’s editor; his son, Giovanni, is the cameraman and his daughter, Letizia, is a reporter. “My biggest mistake was to bring in the whole family,” he told me. “Now they are as obsessed as I am.” The station functions on a bare-bones budget, earning about €4,000 ($5,000) a month from advertising, which covers gasoline and TV equipment but leaves almost nothing for salaries. “We are a little fire that we hope will become a big fire,” Maniaci said, adding that he sometimes feels he is fighting a losing battle. In recent months, Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s government had introduced legislation that could weaken Sicily’s anti-Mafia campaign: one measure would impose stricter rules on wiretapping; another gave tax amnesty to anyone who repatriated cash deposited in secret overseas bank accounts, requiring them to pay only a 5 percent penalty. “We have Berlusconi. That’s our problem,” Maniaci told me. “We can’t destroy the Mafia because of its connection with politics.”

Not every politician is in league with the Mafia. The day after speaking with Maniaci, I drove south from Palermo to meet Corleone Mayor Antonino Iannazzo, who, since his election in 2007, has been working to repair the town’s reputation. The two-lane highway dipped and rose across the starkly beautiful Jato Valley, passing olive groves, clumps of cactus and pale green pastures that swept up toward dramatic granite ridges. At last I arrived in central Corleone: medieval buildings with balustraded iron balconies lined cobblestone alleys that snaked up a steep hillside; two giant sandstone pillars towered over a town of 11,000. In the nave of a crumbling Renaissance church near the center, I found Iannazzo—an ebullient, red-bearded 35-year-old, chomping on a cigar—showing off some restoration work to local journalists and business people.

In three years as Corleone’s mayor, Iannazzo has taken a hands-on approach toward the Mafia. When Salvatore Riina’s youngest son, Giuseppe Salvatore Riina, resettled in Corleone after getting out of prison on a technicality five and a half years into a nine-year sentence for money laundering, Iannazzo went on TV to declare him persona non grata. “I said, ‘We don’t want him here, not because we’re afraid of him, but because it’s not a good sign for the young people,’” he told me. “After years of trying to give them legal alternatives to the Mafia, one man like this can destroy all of our work.” As it turned out, Riina went back to prison after his appeal was denied. By then, says Iannazzo, Riina “understood that staying in Corleone wouldn’t be a good life for him—every time he went out of the house, he was surrounded by the paparazzi; he had no privacy.” Iannazzo’s main focus now is to provide jobs for the town’s youth—the 16 percent unemployment rate is higher here than in much of the rest of Italy—to “wean them off their attraction to the Mafia life.”

Iannazzo got into my car and directed me through a labyrinth of narrow streets to a two-story row house perched on a hillside. “This is where [Riina’s successor] Bernardo Provenzano was born,” he told me. The municipality seized the house from the Provenzanos in 2005; Iannazzo himself—then deputy mayor—helped evict Provenzano’s two brothers. “They took their things and left in silence—and moved 50 yards down the street,” he recalls. Iannazzo was remaking the house into a “laboratory of legality”—a combination of museum, workshop and retail space for anti-Mafia cooperatives such as Libera Terra. The mayor had even had a hand in the design: stark metal banisters suggest prison bars while plexiglass sheets on the floors symbolize transparency. “We’ll show the whole history of the Mafia in this region,” he said, stopping in front of the burned-out remains of a car that had belonged to journalist Pino Maniaci.

Iannazzo still faces major challenges. Under a controversial new law passed by Italy’s parliament this past December, a confiscated Mafia property must be auctioned off within 90 days if a socially responsible organization has not taken it over. The law was intended to raise revenue for the cash-strapped Italian government; critics fear it will put properties back into the hands of organized crime. That’s “a ridiculously short period,” said Francesco Galante, of Libera Terra, who said it can take up to eight years for groups like his to acquire confiscated Mafia assets. And few citizens or even cooperatives can match the Mafia’s spending power. “Judges all over Italy protested against this bill,” Galante told me. “We got signatures and held events to try and stop this decision, but it didn’t work.” He estimates that some 5,000 seized properties could revert to the Mafia. (Since then, a new national agency was created to manage seized assets; Galante says it may mitigate that danger.)

Franco Nicastro, president of the Society of Sicilian Journalists, considers his organization lucky to have acquired one of the most powerful symbols of the island’s dark past before the deadline: the former home of Salvatore Riina in Palermo, where The Beast had lived under an assumed name, with his family, before his capture. A tasteful split-level villa with a date-palm garden beneath mountains a few miles away, it could be a screenwriter’s retreat in the Hollywood Hills. The house provided an atmosphere of suburban comfort to the man who had plotted the murders of Falcone, Borsellino and scores of others in the early 1990s. “He never met any fellow Mafiosi in this place,” Nicastro told me, throwing open shutters and allowing sunlight to flood the empty living room. “This was strictly a place for him, his wife and children.” This year it will reopen as the society’s headquarters, with workshops and exhibitions honoring the eight reporters who were murdered by the Mafia between the late 1960s and 1993. “Riina could kill journalists, but journalism didn’t die,” Nicastro said, leading the way to a drained swimming pool and a tiled patio where Riina liked to barbecue. Acquiring mob properties like this may become more difficult if Italy’s new law takes hold. But for Sicilians awakening from a long, Mafia-imposed nightmare, there will be no turning back.

Writer Joshua Hammer, who is a frequent Smithsonian contributor, lives in Berlin. Photographer Francesco Lastrucci is based in Italy, New York and Hong Kong.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)