Inside Slab City, a Squatters’ Paradise in Southern California

Architect and author Charlie Hailey and photographer Donovan Wylie capture one of America’s last free places

:focal(490x452:491x453)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/8a/378a3028-f90b-4e2a-86b9-758f4d0e0fb7/11731_001_fig_001.jpg)

On a map, Slab City looks like Anytown, U.S.A. Streets intersect in a grid-like fashion and have names like Dully’s Lane, Tank Road and Fred Road. But it’s not until you have “boots on the ground” that the reality of this squatters’ paradise in the desert sinks in.

Situated on 640 acres of public land located about 50 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border in Imperial County, California, Slab City sits on the site of Camp Dunlap, a former U.S. Marine Corps base. During its peak in the 1940s, the camp housed a laboratory for testing how well concrete survived in the harsh climate of the Sonoran Desert, but by the end of World War II, the government shut down operations. Noticing an opportunity, squatters soon staked their claim on the area, building a hodgepodge of residences using the concrete slabs that remained coupled with whatever materials they could find.

Intrigued, author and architect Charlie Hailey and photographer Donovan Wylie set out to delve deeper and explore what has come to be known as the country’s “last free place.” The result is their new book Slab City: Dispatches from the Last Free Place.

Slab City: Dispatches from the Last Free Place (Mit Press)

An architect and a photographer explore a community of squatters, artists, snowbirds, migrants, and survivalists inhabiting a former military base in the California desert.

Under the unforgiving sun of southern California's Colorado Desert lies Slab City, a community of squatters, artists, snowbirds, migrants, survivalists, and homeless people. Called by some “the last free place” and by others “an enclave of anarchy,” Slab City is also the end of the road for many. Without official electricity, running water, sewers, or trash pickup, Slab City dwellers also live without law enforcement, taxation, or administration. Built on the concrete slabs of Camp Dunlap, an abandoned Marine training base, the settlement maintains its off-grid aspirations within the site's residual military perimeters and gridded street layout; off-grid is really in-grid. In this book, architect Charlie Hailey and photographer Donovan Wylie explore the contradictions of Slab City.

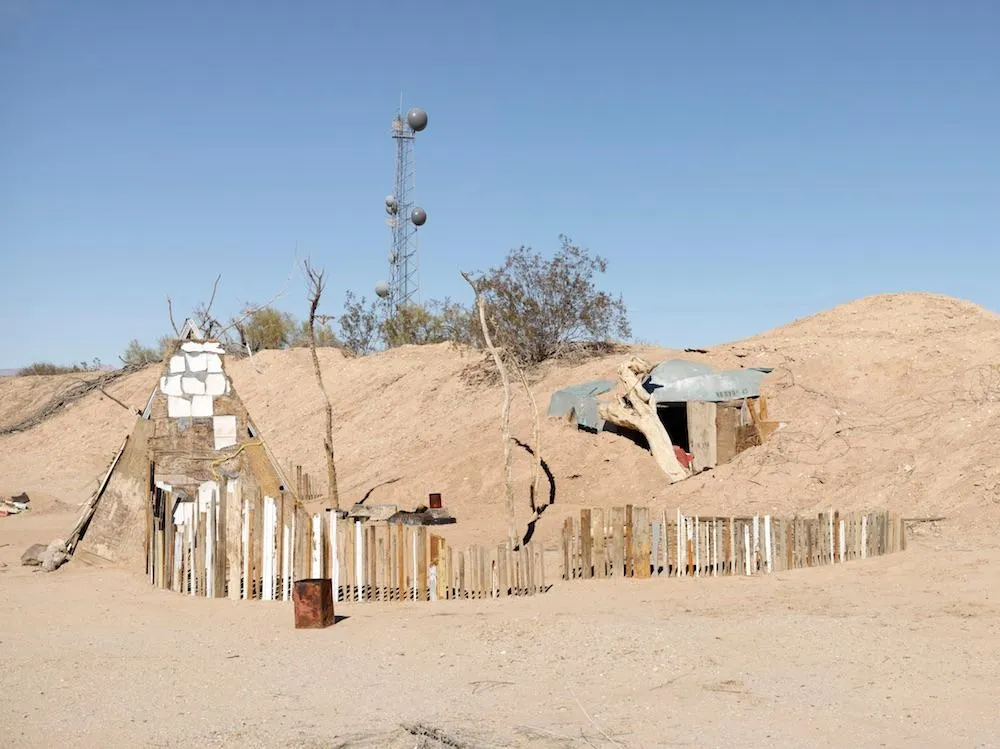

In a series of insightful texts and striking color photographs, Hailey and Wylie capture the texture of life in Slab City. They show us Slab Mart, a conflation of rubbish heap and recycling center; signs that declare Welcome to Slab City, T'ai Chi on the Slabs Every morning, and Don't fuck around; RVs in conditions ranging from luxuriously roadworthy to immobile; shelters cloaked in pallets and palm fronds; and the alarmingly opaque water of the hot springs.

At Camp Dunlap in the 1940s, Marines learned how to fight a war. In Slab City, civilians resort to their own wartime survival tactics. Is the current encampment an outpost of freedom, a new “city on a hill” built by the self-chosen, an inversion of Manifest Destiny, or is it a last vestige of freedom, tended by society's dispossessed? Officially, it is a town that doesn't exist.

How did you first find out about Slab City?

Charlie Hailey: I heard about Slab City about 20 years ago when I started doing research for a dissertation on the practice of camping and visited Slab City for the first time. But it was really after Donovan and I started a conversation years later about some of our common interests that we came up with the idea to revisit it.

What were your initial thoughts upon arrival and how did the residents react when you got there?

Hailey: One of the first things for me was the question of orientation. It’s interesting because there’s a strong memory of a grid, so that helps with orientation, but in many ways that grid has been—not necessarily erased—but things have been built over it or it’s overgrown. So I was constantly reorienting myself to the place.

We didn’t set out to interview the residents, we were really interested in the boundaries and structures and how and why Slab City was made. It’s not that we didn’t want to talk to them, but that wasn’t our explicit purpose. It was interesting to have informal conversations with the residents, but we were mostly ignored. Some people thought we were from the county and doing surveys, and some weren’t necessarily happy with us being there. There was a whole range of responses.

Donovan Wiley: Our motivation was to understand the structure of Slab City. We wanted to find the former perimeters of the military base, which made us sort of like archeologists and surveyors at the same time. We were interested in the constructive environment and how people were forming spaces of territory on this site. In some ways we became invisible, but we did engage with the community and had some interesting conversations.

Charlie, as an architect, what struck you the most about Slab City’s infrastructure?

Hailey: Since Slab City was previously a relatively large military installation, what really impresses me is the scale of the infrastructure. Even though it no longer functions as a base, the infrastructure of a working town is still there—or at least some of the remnants are—and yet it’s completely off the grid in almost every aspect of services, however [the layout] is a grid. Ultimately the slabs themselves are that autonomous infrastructure that gave it its name. We were fascinated with the idea of concrete on sand. Concrete is permanent in terms of architecture, and yet [the slabs] float on the sand. They really are invitations for settlement. They provide a floor and give some stability to an incredibly transient place.

What were some of the more interesting dwellings that you saw?

Wiley: [The dwellings] were all so autonomous and each had its own individuality, which in itself makes them interesting. The structures were people; they revealed the people and the place and were all very different and fascinating. [Being there] really made me question the idea of what being free is, and what it means in terms of American mythology, the desert, expansion and history.

Hailey: The scale of construction ranged from a piece of cardboard on the ground placed within a creosote bush to these large telephone structures to pallet structures that were two stories tall. Each one expressed what that particular person wanted to make them, but then against restraint of what resources were there and what nature would allow. It was windy and it was hot, and yet you’re trying to make home in a very unhomely place.

Conditions in the desert, where Slab City is located, can be harsh. Why do its occupants stick around?

Hailey: It’s a public space, and it’s been public land since the grid was laid out. The amount of control of what you can do there is limited. I think also the identity of the place is something that people find attractive. That “last free place,” we didn’t make that up, it’s a phrase that the occupants use and believe. One of the things we were interested in was how they’re testing freedom.

Wiley: The slabs invite you to make a place, and there’s an infrastructure that can invite you. Also, there’s something about not being reached. There are clearly people there who don’t want to be found, so there’s something about disappearing, and the desert offers that kind of opportunity.

After spending time there, what are your thoughts on that idea of the "last free place"?

Hailey: It’s quite complicated, at least from my perspective, because [freedom] is measured by a greater control, whether it’s the environment or other conditions that the residents are experiencing. What many of them are doing is preserving and curating the idea of freedom.

Wiley: I think that’s spot on. There’s also this idea of preservation and perception of freedom, and the people who live there are taking ownership of that. I think it’s fascinating and admirable.

Slab City: Dispatches from the Last Free Place is published by MIT Press and will be available October 2018.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/8a/378a3028-f90b-4e2a-86b9-758f4d0e0fb7/11731_001_fig_001.jpg)