Inside the ER at Mt. Everest

Dr. Luanne Freer, founder of the mountain’s emergency care center, sees hundreds of patients each climbing season at the foot of the Himalayas

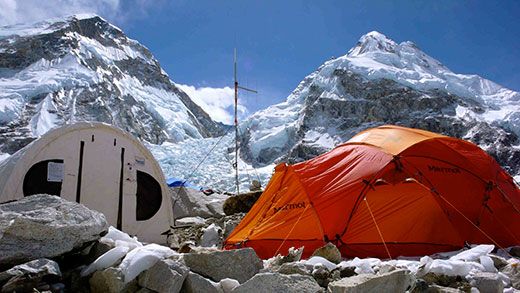

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mount-Everest-base-camp-631.jpg)

A middle-aged woman squats motionless on the side of the trail, sheltering her head from the falling snow with a tattered grain sack.

Luanne Freer, an emergency room doctor from Bozeman, Montana, whose athletic build and energetic demeanor belie her 53 years, sets down her backpack and places her hand on the woman’s shoulder. “Sanche cha?” she asks. Are you OK?

The woman motions to her head, then her belly and points up-valley. Ashish Lohani, a Nepali doctor studying high-altitude medicine, translates.

“She has a terrible headache and is feeling nauseous,” he says. The woman, from the Rai lowlands south of the Khumbu Valley, was herding her yaks on the popular Island Peak (20,305 feet), and had been running ragged for days. Her headache and nausea indicate the onset of Acute Mountain Sickness, a mild form of altitude illness that can progress to High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE), a swelling of the brain that can turn deadly if left untreated. After assessing her for HACE by having her walk in a straight line and testing her oxygen saturation levels, the doctors instruct her to continue descending to the nearest town, Namche Bazaar, less than two miles away.

Freer, Lohani and I are trekking through Nepal’s Khumbu Valley, home to several of the world’s highest peaks, including Mount Everest. We are still days from our destination of Mount Everest Base Camp and Everest ER, the medical clinic that Freer established nine years ago, but already Freer’s work has begun. More than once as she has hiked up to the base camp, Freer has encountered a lowland Nepali, such as the Rai woman, on the side of the trail ill from altitude. Thankfully, this yak herder is in better condition than most. A few weeks earlier, just before any of the clinics had opened for the spring season, two porters had succumbed to altitude-related illnesses.

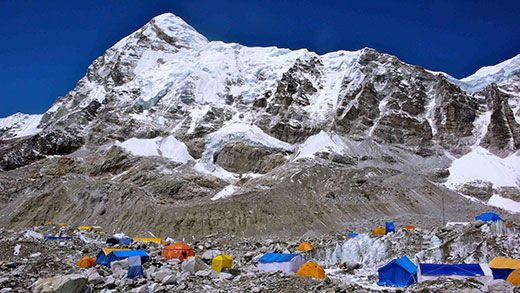

Each year over 30,000 people visit the Khumbu to gaze upon the icy slopes of its famed peaks, traverse its magical rhododendron forests and experience Sherpa hospitality by the warmth of a yak dung stove. Some visitors trek between teahouses, traveling with just a light backpack while a porter carries their overnight belongings. Others are climbers, traveling with a support staff that will aid them as they attempt famous peaks such as Everest (29,029 feet), Lhotse (27,940 feet) and Nuptse (25,790 feet). Many of these climbers, trekkers and even their support staff will fall ill to altitude-induced ailments, such as the famed Khumbu cough, or gastro-intestinal bugs that are compounded by altitude.

A short trip with a group of fellow doctors to the Khumbu in 1999 left Freer desperate for the chance to return to the area and learn more from the local people she had met. So in 2002 Freer volunteered for the Himalayan Rescue Association’s Periche clinic—a remote stone outpost accessed by a five-day hike up to 14,600 feet. Established in 1973, Periche is located at an elevation where, historically, altitude-related problems begin to manifest in travelers who have come up too far too fast.

For three months, Freer worked in Periche treating foreigners, locals and even animals in cases ranging from the simple—blisters and warts—to the serious, instructing another doctor in Kunde, a remote village a day’s walk away, via radio how to perform spinal anesthesia on a woman in labor. Both the woman and the baby survived.

It was during that year, on a sojourn up to Everest Base Camp, that Freer hatched the plan of developing a satellite clinic for the Himalayan Rescue Association at the base of the famed peak. While many expeditions brought their own doctors, there was no formal facility, which Freer knew could help increase the level of care. While working at Periche, Freer had seen numerous patients sent down from Everest Base Camp, and the gap between many doctors’ experience and the realities of expedition medicine concerned her.

“I saw several well-intentioned doctors nearly kill their patients because they didn’t understand or hadn’t learned proper care of altitude illness and wilderness medicine,” she says. The mountain environment had always held an allure for Freer. Upon finishing her residency in emergency medicine at Georgetown University, she headed west for the mountains, landing a job as a doctor in Yellowstone National Park, where she still works full time, serving as the park’s medical director. Freer is a past president of the Wilderness Medical Society, and her unique niche has taken her not only to the Himalaya but also to remote places in Africa and Alaska.

“Expedition medicine is a specialty in and of itself. Few doctors have the skills and background to be a good expedition doctor without a pretty substantial investment in self-learning,” she says. “Unfortunately, many just try to wing it.”

Freer was also struck by what she perceived as a discrepancy between the care some doctors were providing the paying clients versus the local staff—in many cases making the Nepalese walk (or be carried) down to the HRA’s clinic at Periche or, for more serious cases, the Sir Edmund Hillary Foundation’s hospital located in Kunde, an additional day away. “I saw a way to continue using the mission of the HRA by treating Westerners and using the fees to subsidize care for the Sherpa,” explains Freer.

Each spring for the past nine years Freer has made the ten-day trek up to Everest Base Camp, often staying for the entire two-and-a-half-month season, and walking with her is like traveling through a well-loved local’s neighborhood, not someone who is halfway around the world from home. At each teahouse and frequently along the trail, Sherpa—grateful patients or friends and relatives of patients from years past—quietly approach Freer with a soft “Lulu Didi.” (Didi is the customary term for “older sister.”)

“It makes me squirm when people call this work, what I do—‘selfless,’” says Freer. “What I do feels very selfish, because I get back so much more than I give. It turns out that’s the magic of it all.”

Freer and the rest of the Everest ER doctors have been in camp for less than 48 hours and already they have dealt with a deceased body from a few seasons past, inadvertently unearthed in the moraine by Sherpa constructing camps, and have seen close to a dozen patients in their bright yellow dining tent as they wait for the clinic’s Weatherport structure to be erected. One Sherpa complains of back pain after a week’s worth of moving 100-plus pound boulders—part of preparing flat tent platforms for incoming clients. Another man can hardly walk because of a collection of boils festering in a sensitive region. A Rai cook who has worked at Everest Base Camp for multiple seasons is experiencing extreme fatigue and a cough, which the doctors diagnose as the onset of High Altitude Pulmonary Edema.

With the exception of the cook, who must descend, all the patients are able to remain at base camp, with follow-up visits scheduled for subsequent days. Each man I ask explains that without Everest ER’s help, they would either have to wait for their expedition to arrive with the hopes that their team leader would be able to treat them, or descend to see a doctor. The ability to stay at Everest Base Camp is not only logistically easier but also means the men do not risk losing their daily wage or, in the case of some lower-tier companies, their job.

The ER’s locale might be glamorous, but the work is often not. Headaches, diarrhea, upper respiratory infections, anxiety and ego-related issues disguised as physical ailments are the clinic’s daily bread and butter. And although the clinic’s resources have expanded dramatically over the past nine years, there is no escaping the fact that this is a seasonal clinic housed in a canvas tent located at 17,590 feet. When serious incidents do occur, Freer and her colleagues must problem solve with a severely limited toolbox. Often the handiest implement is duct tape.

“There is no rule book that says, ‘When you’re at 18,000 feet and this happens, do x.’ Medicine freezes solid, tubing snaps in the icy winds, batteries die—nothing is predictable,” says Freer. But it’s that challenge that keeps Freer and many of her colleagues coming back. This back-to-basics paradigm also engenders a more old-fashioned doctor-patient relationship that Freer misses when practicing in the States.

“Working at Everest ER takes me back to what took me to medical school in the first place—helping people and having time to actually spend with them,” she says. “I’m just doing what I think is best for the patient—not what the insurance company will reimburse.”

While Everest ER is now a well-established part of the Everest climbing scene, there have certainly been bumps in the trail, particularly that first year in 2003. While the HRA backed the idea of the clinic, Freer had to find financial support elsewhere. Critical pieces of equipment never arrived, and one day while treating a patient, the generator malfunctioned, rendering radios and batteries needed for oxygen concentrators useless; the foot pedal to the hyperbaric chamber broke; IV fluids were freezing en route to a patient’s veins; and all the injectable medications had frozen solid. As if that weren’t enough, the floor was covered in water as the glacial ice melted from below.

There have also been mountain guides who say that although they are grateful for the care the doctors provide, they lament Everest Base Camp’s ever expanding infrastructure of which Everest ER is just another example. Everest ER lessens an expedition’s ethic of self-reliance and the all-around know-how on which the guiding profession prides itself.

But nonetheless, since Everest ER first rolled back the tent flap, the clinic has seen over 3,000 patients. Among the approximately 30 critical cases, there have been causes for celebrating as well, including marriage proposals, weddings and women who discover that their nausea and fatigue are due not to dysentery, but a long- awaited pregnancy. The spring of 2012 will mark Everest ER’s tenth anniversary.

“After nine seasons, if we have significantly impacted 30 lives, if we helped return 30 people to their families, that is an amazing bit of work. Even one makes it worth all the effort,” says Freer.

“But 30? Wow, that’s something to feel good about.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.