Instead of Being Swallowed by a Mine, This Arctic Town is Moving

The people of Kiruna are moving their entire town brick-by-brick

For the last 115 years, a small town in Sweden’s northern Arctic region and the world’s largest underground iron ore mine have depended on one another. The mine provides the town with an economy and employment, and the town provides workers. Town and mine are so interconnected they even have the same name: Kiruna. But now the mine is threatening the town, creating giant fissures capable of swallowing buildings whole. The municipality of Kiruna has two choices—stop mining operations and allow the town to die, or move 18,000 people to a safer location. In a highly unusual—if not unprecedented—decision, the citizens of Kiruna have decided to pack up their belongings, lives and history, and relocate two miles away.

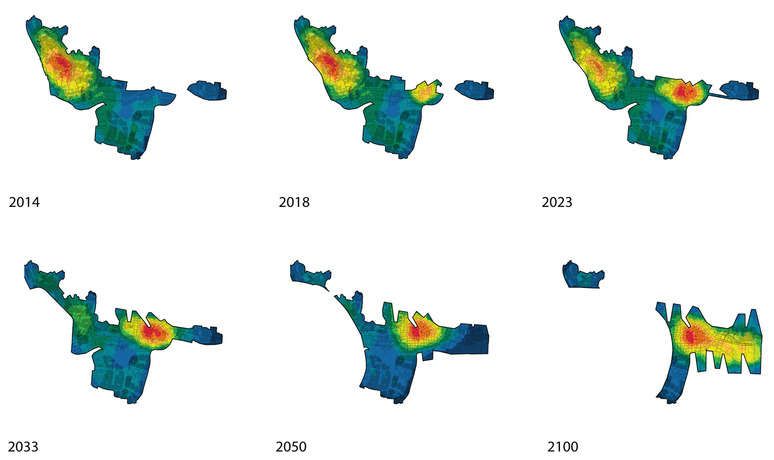

This massive move is not going to happen overnight, however. While the great migration began last June and the building demolition got underway in late April, the final completion date for the relocation is 2033. There is also a 100-year master plan that calls for the new Kiruna to be larger, more modern and less reliant on the mine.

The symbiotic existence between town and mine started in 1900, when the (now state-owned) mining company Luossavaara-Kirunavaara AB (LKAB) first established Kiruna as a company town. In 2004, LKAB informed Kiruna that to continue mining iron ore they would need to dig the mine at a 60 degree slope directly under the town, putting nearly 3,000 homes and public buildings at risk. After years of debate and discussion, local government officials decided to move the entire municipality of Kiruna two miles east, with LKAB footing nearly the entire $2 billion bill, ensuring both the survival of the town’s economy and its buildings.

This, of course, is easier said than done. In 2011, White Arkitekter, in collaboration with the Norwegian firm Ghilardi + Hellsten, won an international competition to design the new Kiruna. The project is much more than just blueprints and concept art: It is also about giving the citizens of Kiruna hope for the future while celebrating the past. To help, a social anthropologist has been employed to better understand the mindset of the citizens and the best way of accomplishing this delicate task.

About a year ago, the firm revealed its plans for the new town—complete with a new city hall, a city center, plenty of public spaces and modern housing. Additionally, the firm and municipality identified 21 buildings of “significant cultural importance” that will be moved brick-by-brick, at the expense of LKAB, to the new town. This includes the local 100-year-old church, which was voted Sweden's most beautiful building in 2001, and the Länsmansbostaden, or Sheriff's House.

Krister Lindstedt, the co-lead architect on the Kiruna project for White Arkitekter, notes how difficult the situation was for the people of the town. “They knew they had to move and that they and their children will no longer be able to use the old streets, but they didn’t know where they were going to go,” said Lindstedt. After the plans were announced, though, the future became clearer. “Now, that has changed. There’s a vision. There are images of a new city. There’s a place. Talking to people, there is a sense we all have moved forward.”

Recently, cracks have started to appear in the west side of the city, giving a physical manifestation of the danger the old Kiruna faces. While the relocation is being done well ahead of any potential for collapse (Lindstedt notes that the land will noticeably shift horizontally before moving vertically), there is a possibility the town will have to move again. “There is a chance … you want to move to a place where there is no risk at all of this happening again, but on the other hand, it is very important to keep the city together. It is such a small community.”

As this process unfolds over the next decades, it is a clear example of how the lives of people and industry intersect. While Kiruna may be small in size, the way they’ve chosen to deal with this situation could have an enormous impact on what other communities do if faced with a similar dilemma.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.