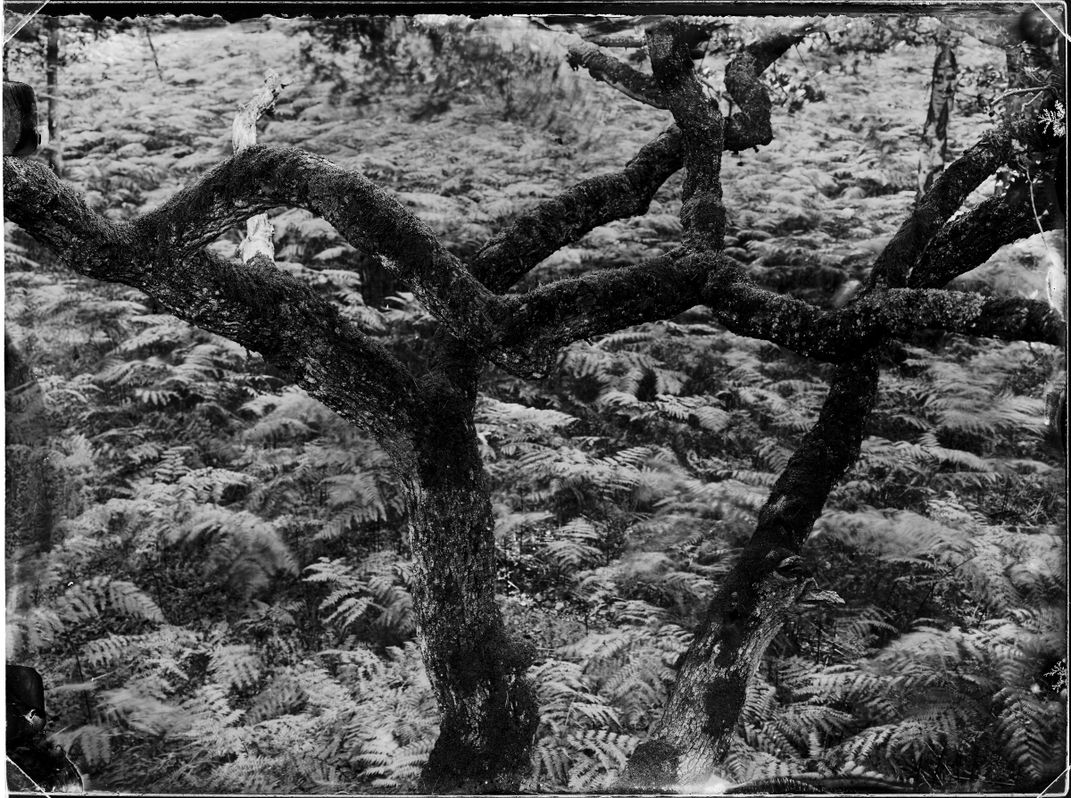

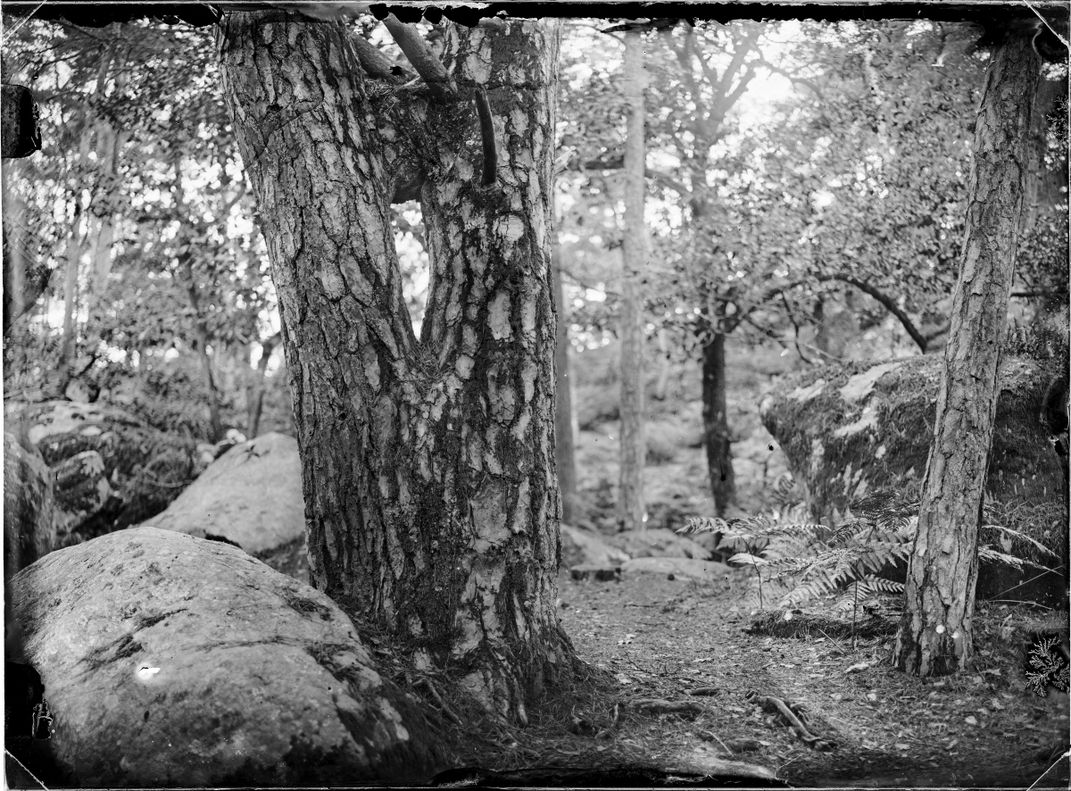

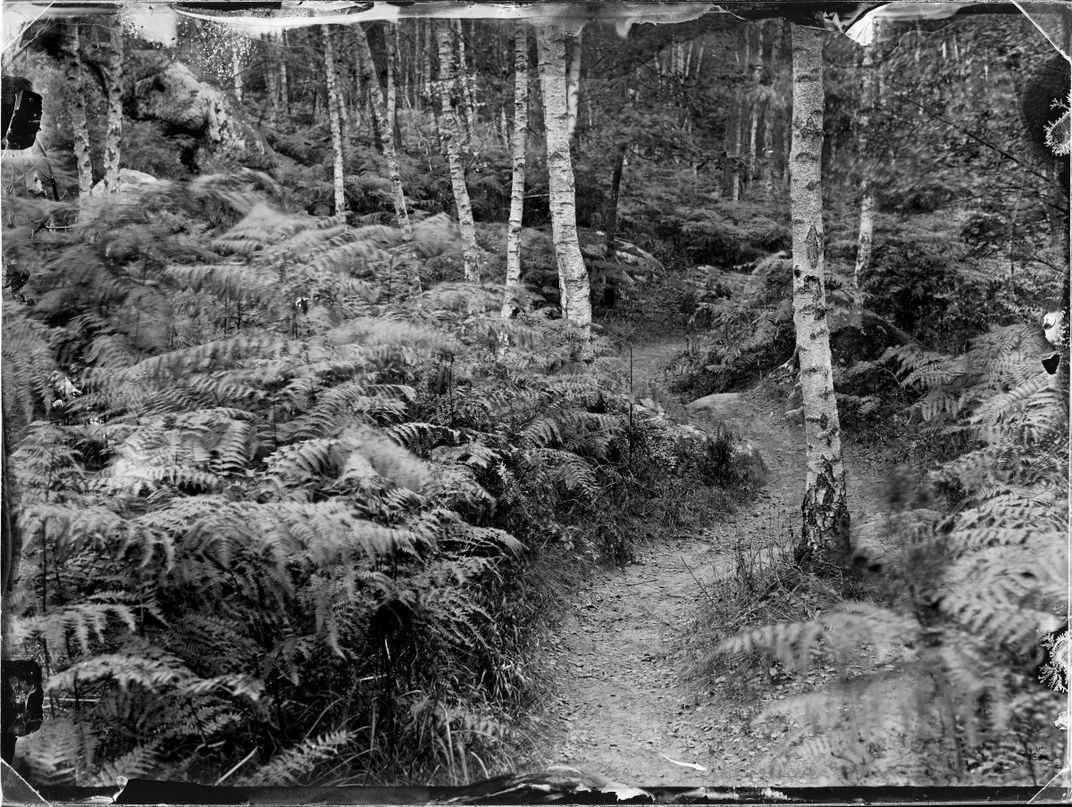

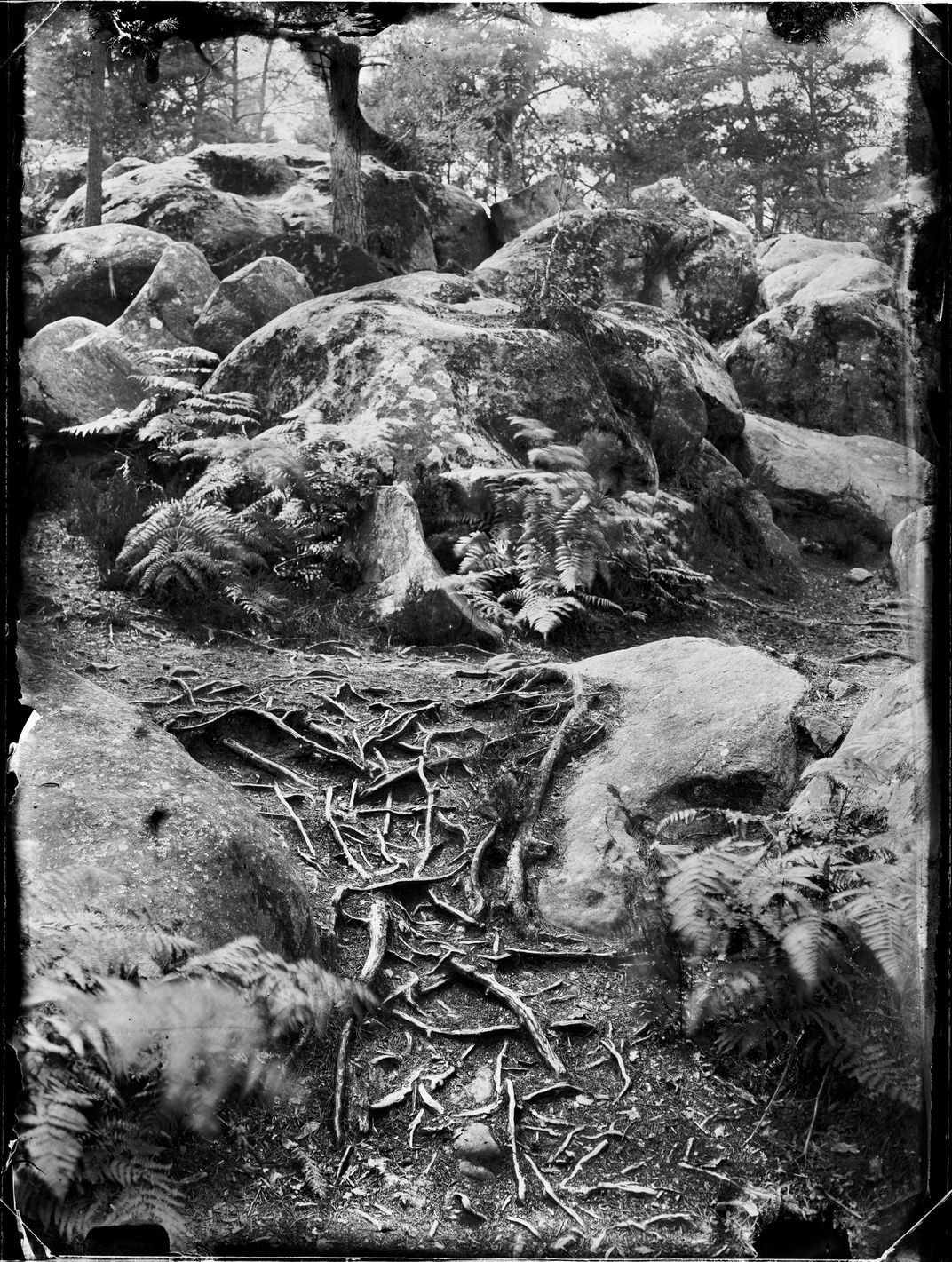

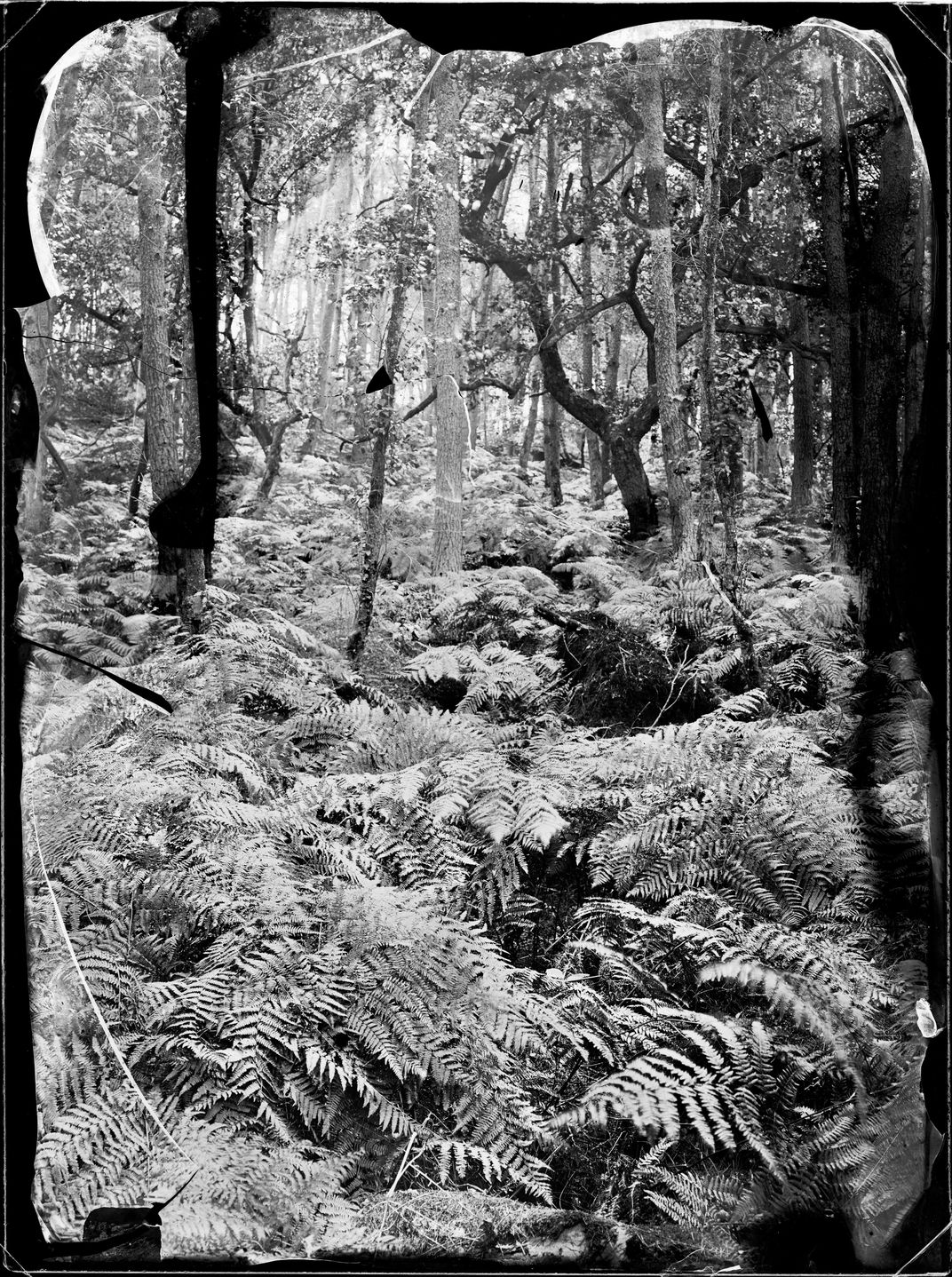

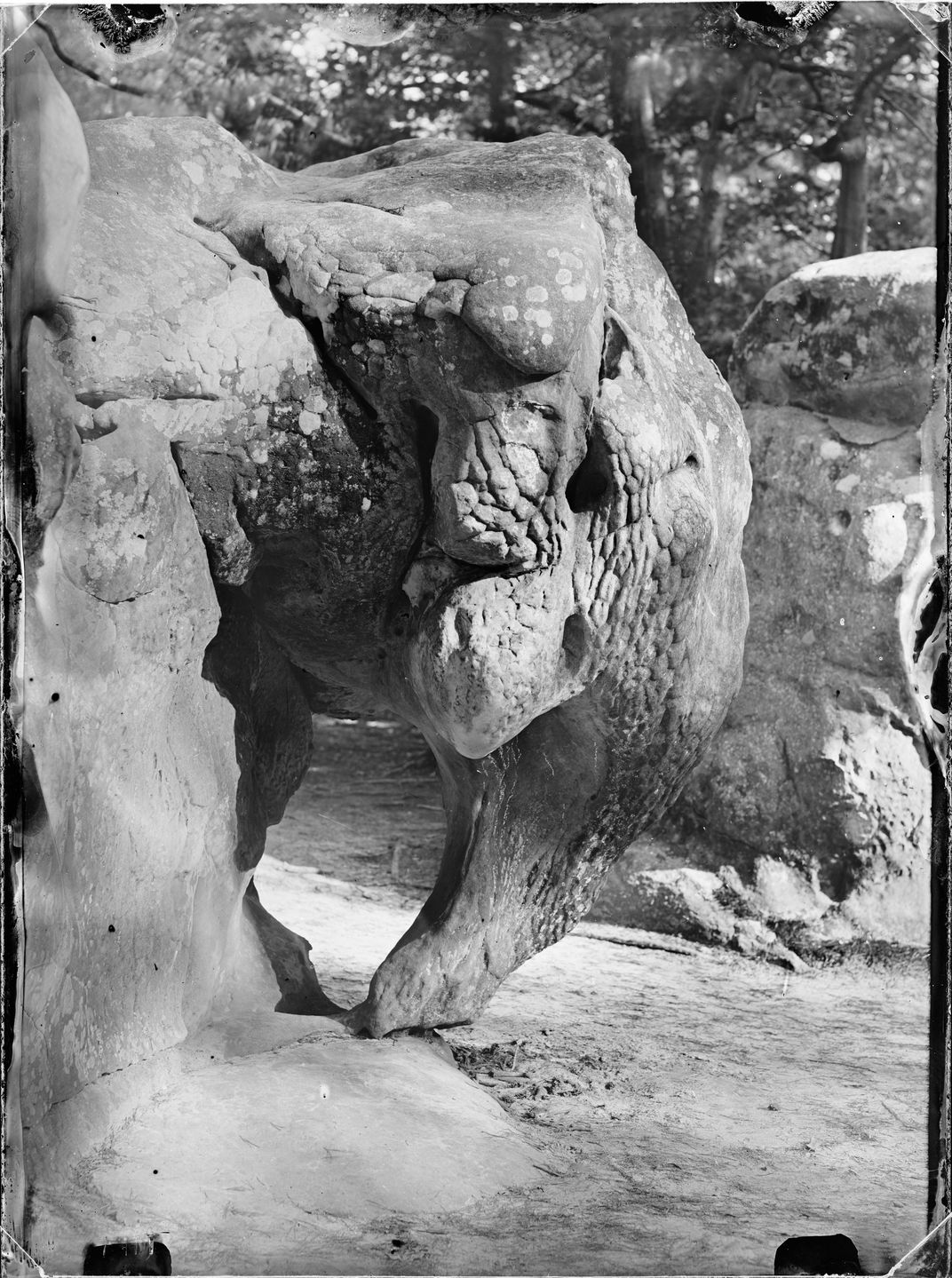

The magic of the forest revealed itself slowly. Strange-looking boulders adorned the landscape “in the most diverse and bizarre forms,” wrote one observer, “like herds of monsters grazing at the bottom of a valley.” When the sun burst through winter clouds, stripes of sunlight penetrated the oaks and beeches and Scots pines, turning grayish grass an iridescent green. Tree trunks were bathed in an orange glow, and fields of dried ferns lit up in pale yellow.

For the French, the name of this forest, Fontainebleau, evokes the elaborate 1,500-room chateau at its heart. From the 12th century on, the kings of France used the site, rich in deer and wild boar and close to Paris, as a hunting ground. In the 17th century, Louis XIV launched a grand initiative to expand the forest, which was followed much later by large-scale plantings of oaks, beeches and pines. Enlarged again in 1983, the forest now covers more than 50,000 acres, an area roughly three times the size of Manhattan.

But the story of the forest’s real magician is little known. Claude-François Denecourt was a career soldier in the French Army, but was dismissed from his post as concierge of a Fontainebleau barracks in 1832 because of his supposed liberal views. He took to wandering in the forest to combat his depression and there discovered the essential pleasures of traipsing through nature. From then on, he devoted himself to developing and promoting the Fontainebleau forest for the general public. Today he should be recognized and appreciated as both a clever entrepreneur and a pioneer—if not the inventor—of nature tourism.

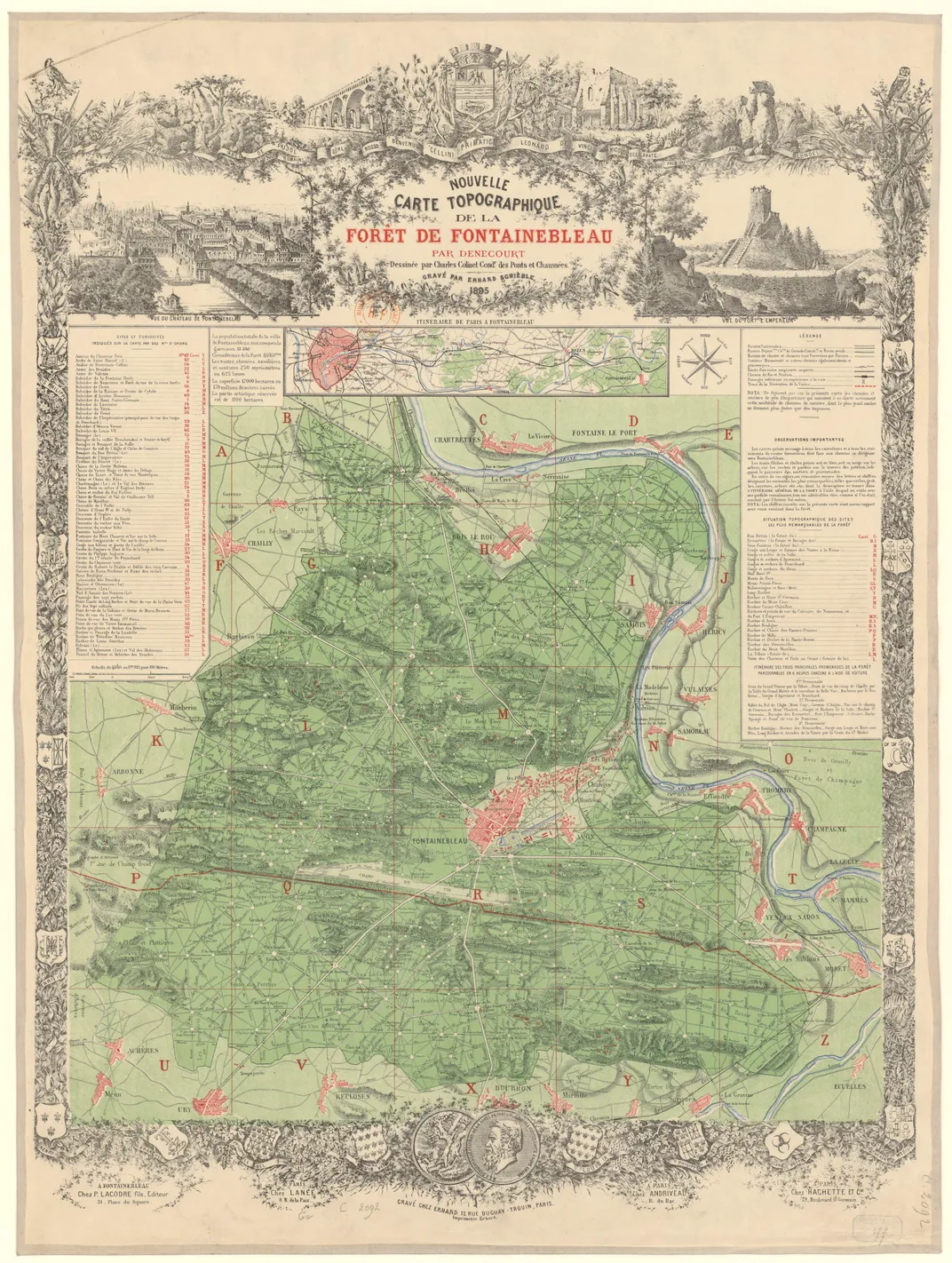

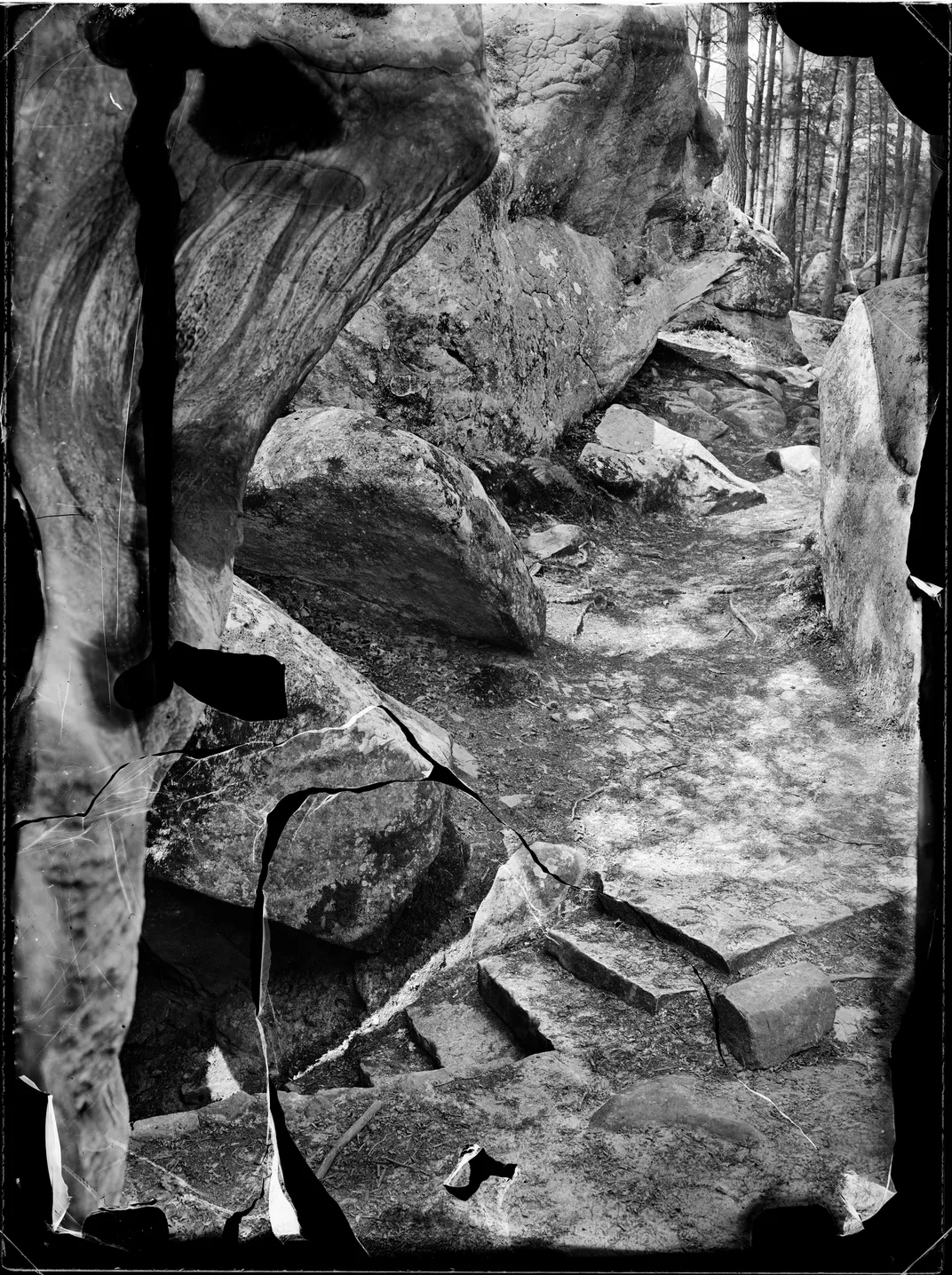

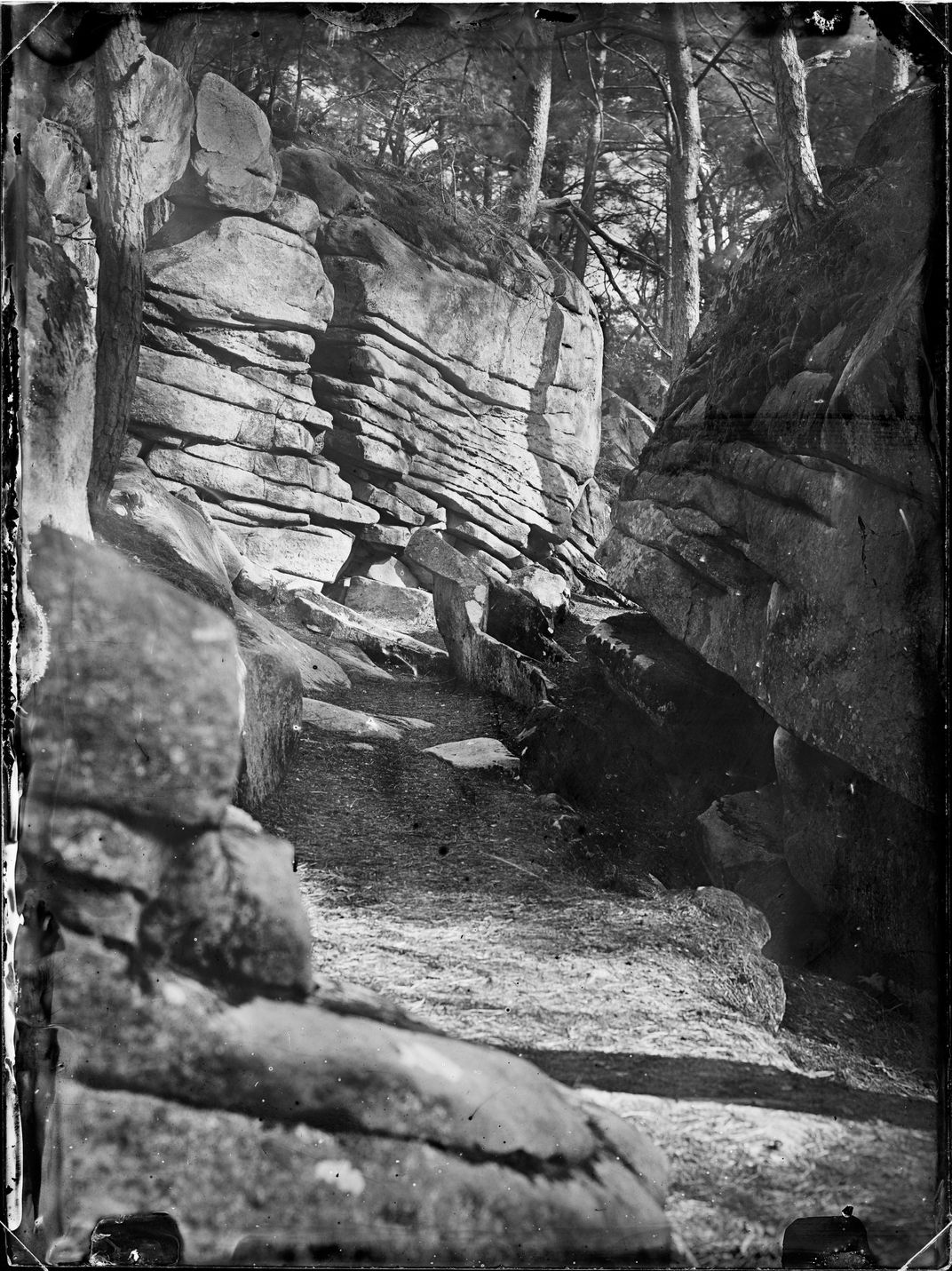

Denecourt’s genius was to recognize the forest’s unique character. Millions of years ago, the forest lay under the ocean, and the receding waters left behind sandy dunes and small deserts and rocky plateaus with thousands of unusual rock formations. Until he came along, the paths through the forest were broad and straight, designed to accommodate royal carriages during hunting seasons. With no legal authority, only the good will of local forest officials, Denecourt carved miles of sinuous hiking trails around the rocks and between the trees. He constructed monuments and stairways out of sandstone, which was plentiful. He dug out caves, grottoes and underground passages, and built fountains even though there was no water to feed them.

No matter that his work was a manipulation of nature designed to look “natural.” The French have long elevated the cultivation of beauty into a fine art—in architecture, food, fashion, design, even fragrance. Nothing is left to chance. Denecourt fit neatly into that tradition. He seduced the traveler with the promise of exploration, adventure and serenity, and he turned the forest into a moneymaker. The paths were the world’s first marked rambling trails, called sentiers bleus, or “blue pathways,” because they were—and still are—marked by blue lines, painted on trees and rocks in the same shade of blue as the uniforms in the revolutionary army. He lured Parisians with best-selling guidebooks as well as maps, engravings and lithographs that made the forest irresistible. He gave some tours himself and steered visitors to refreshment stands and souvenir shops inside the forest, many of which conveniently sold his own publications.

“O you who, to discover and admire the capricious wonders of the world, travel the earth and brave the seas, come to Fontainebleau,” Denecourt wrote. “Yes, come to Fontainebleau to visit...its delicious vistas where spellbound eyes take in more than a thousand perspectives whose beauties have inspired so many artists, so many poets, lovers passionate about fertile and wonderful nature. Oh! yes, come to Fontainebleau to taste the pure air of our rocks, the sweet fragrance exhaled by our woods and our wildflowers.” Denecourt entertained visitors with legends, many of which he simply made up. Taking inspiration from history, art, mythology and his own imagination, he reportedly assigned names to more than 600 trees, 700 rock formations and assorted lookouts. There are oaks named for Charlemagne and Marie-Antoinette. One rocky outcropping became the Cyclops Passage. Not everybody was enchanted. The landscape painter Théodore Rousseau deplored the markings and inscriptions “bespoiling and dishonoring” the forest. But Denecourt’s success was guaranteed with the arrival of the railway in 1849, which brought Parisians on day trips in what were called “pleasure trains.”

In 1861, eleven years before Yellowstone was made the first national park in the United States, a portion of Fontainebleau became the world’s first nature preserve. Denecourt and Charles Colinet, a disciple of his who continued the work after Denecourt’s death in 1875, created 18 marked hiking trails covering 120 miles. Today they are part of a larger network of 21 paths covering nearly 200 miles. The forest attracts millions of visitors each year: hikers, bicyclists, picnickers, riders on horseback, rock climbers and wanderers eager to escape the city. The National Office of Forests fells, prunes and replants trees; rebuilds the manmade stone staircases and walls and benches; digs sand out of the caves; replants vegetation to stabilize hills; and shores up the rock formations. The Association of the Friends of the Forest of Fontainebleau, a private organization, helps to maintain the walking trails and publishes guidebooks and maps. (Like all parks in France, the forest was closed indefinitely in March to combat the spread of coronavirus.)

One of the most beloved of Denecourt’s showpieces is the Grotte du Serment, or Grotto of the Oath, on Sentier No. 8, a large shelter he created by digging deep into the sand floor beneath a ceiling of giant boulders and building walls of stone. On the day I visited, I followed the daylight, emerging from the other end of the grotto to see an old graffito scratched into a rock: “DFD 1853.” Denecourt had nicknamed the site the dernière folie de Denecourt, the last folly of Denecourt, promising it would be his last creation, a promise he did not, ultimately, keep. He followed it with another rocky cave. Having broken his oath, he named it Grotte du Parjure—the Grotto of Perjury.

Elsewhere, perched on a mound in a clearing, I found the stone observation tower that bears Denecourt’s name. It was considered so important that Emperor Napoleon III and his wife, Empress Eugénie, inaugurated the site. A bronze medallion with Denecourt’s profile adorns a tower wall. I climbed the 47 stone stairs to the lookout at the top. In the distance, the tree line ended. I understood the passion that seized the great nature-worshiping painters of the Barbizon and Impressionist schools, from Jean-François Millet and Théodore Rousseau to Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and brought them to paint the forest from dawn to darkness. The Seine River flowed, unseen, softly curving, in the valley below. Paris was only 40 miles, but it seemed a world away.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c2/a3/c2a3174b-61c0-4e37-b5c6-4ea19d62564f/mobile__600x350_hiking.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/80/f280e077-6d16-429a-9f0b-5ab5f9b3f5b2/opener_may2020_f14_hiking.jpg)