“I’ve Lived the Life of 500 People”: The Photography of Art Wolfe

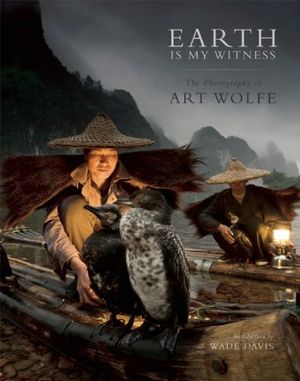

Earth Is My Witness chronicles Wolfe’s 40-year career as a photographer

For five decades, Art Wolfe has traveled the globe, camera in hand, documenting everything from bull elephants in Botswana to blue icebergs in Antarctica. In Earth Is My Witness: The Photography of Art Wolfe, his life's work is laid out across more than 400 glossy pages, offering readers a chance to immerse themselves in the threatened places, animals and cultures that he has dedicated his career to capturing. The book is both a testament to a prodigious career and a celebration of a man who has devoted his life to conservation photography.

Wolfe is no stranger to publishing: Since 1989, he has released at least one book a year, but he looks at Earth Is My Witness through a different lens. "I've done 80 books," Wolfe told Smithsonian.com, "and if anyone has entertained the idea of owning one of my books, I think this is the book that covers all the bases. I'm very proud of it." Wolfe travels nearly nine months out of the year, but recently spoke with us from his Seattle office about his lengthy career, avoiding "writer's block" and the places he most wants to see to next.

Smithsonian: How did you come to photography?

Wolfe: I was an art major at the University of Washington, but also during those college years I got into climbing. I was always a young naturalist—I always loved the natural world, and as I got older, I got more and more into hiking up into mountains and onto glaciers. During the week I’d go to school and learn about composition, and on the weekends, I got a little camera to document the climbs. My allegiances shifted during those college years. I absorbed everything I was learning in art school and applied it to my photos. By the time that I graduated, I saw myself as a photographer rather than a painter.

What did photography offer that was different from fine art?

It was much easier to create original compositions through the photographic process than to try to sit and stare at a blank piece of canvas or watercolor paper and create a meaningful composition. And I started seeing, fairly fast, that the camera could be a ticket to travel. I've always wanted to see what was beyond the ocean. Living on the West Coast you look out across the ocean toward Asia, and the camera became a passport into the unknown: to cultures, to countries that I wanted to see.

The book is a massive 400-page collection of photographs from your entire career thus far. How has your approach to photography and to capturing what you see changed or evolved? Can we see that in the book?

I think the greatest thing that art gave me was the insatiable curiosity to look at what I was doing but not to be completely satisfied and lulled into a sense of complacency. With people, there are classic portraits, there are candid moments, but there's also a subset of photos where I've completely created an abstract composition, where I've arranged up to 60 monks in a rosette below me in a monastery on the outskirts of Katmandu. A lot of people would condemn that and say that I'm altering reality, but wearing the hat of an artist ... I've given myself permission to do that.

The thing I was trying to avoid was something analogous to writer's block, where you run out of ideas. Fine art training and studying art taught me and encouraged me to evolve my work and never to get in a rut and shoot the same thing forty years later, and that has kept me excited and moving forward in a positive direction.

What do you find that inspires you most?

Capturing an image that may be a very private moment between you and a subject, but if it's successful, it can be seen and witnessed by millions of people around the globe. I think that's the undercurrent of almost everything I've done over the last 40 years. It's why sculptors sculpt and writers write and painters paint ... communicating a thought and idea that, if successful, reaches a broad audience. I wear the hat of a communicator. I photograph for my own enjoyment, but that in and of itself wouldn't do it. It's communicating, inspiring and encouraging people through the photographic medium that really puts the fire in my belly.

There's this idea, among people who study memory, that in order to feel as though you've lived a long life, it's not necessarily about living a lot of years but doing a lot of things, and having a lot of memories to fill those years. I look at your book, and I see all of the places you've been and all the memories you must have—is there one, or a few, in particular, that stands out to you?

I totally agree with that. My father passed away when he was 94 a couple of years ago. I would come home from yet another trip and he was living in an assisted care facility very close to where I lived, and I would naturally stop by before I even went home. And he was looking at me under the covers kind of worried, and I said "Are you worrying about me?" And he would nod, and I would say, "Listen, I’ve lived the life of 500 people. I've seen all of the charismatic animals I've ever wanted to see, from snow leopards to giant pandas to mountain gorillas to great white sharks. I've been all over the Earth, I've lived the life of 500 people; do not worry about me. Take care of yourself."

When I first looked at that book as a published book, with all the photos in it, it was humbling. I felt humbled by having been to the Karakoram Range and looking at K2, or being involved in the first Western expedition to Tibet, or being in the heart of the Amazon and witnessing tribes that hadn’t been exposed to the outside world. All of those—almost any one of those photos that I focus on in that book will have an etched memory in my brain. I cannot remember the names of people I taught two days ago, but show me an image and I can tell you a story about it with clarity.

Having done so much—having lived those 500 lives—what's next? Are there places you haven't been that you want to go?

I've got like five or six books in my mind, many of which I've been working on. The fear is running out of ideas, writer's block. Creative energy courses through my body. I'll always be working on something, I'll never be retired.

There are a lot of places I've never been: Egypt, Spain, places that people would maybe think would be the first places I would go. I'm holding those off until I get a little older. I want to go through the Middle East.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/natasha-geiling-240.jpg)