The City Nobel Laureate Joseph Brodsky Called Paradise

A journalist recalls his witching-hour walk through Venice with the famous poet

:focal(541x204:542x205)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ad/bf/adbff005-4f1a-4b2b-8cf9-862906e21d88/sqj_1510_venice_brodsky_03-web-resize-v2.jpg)

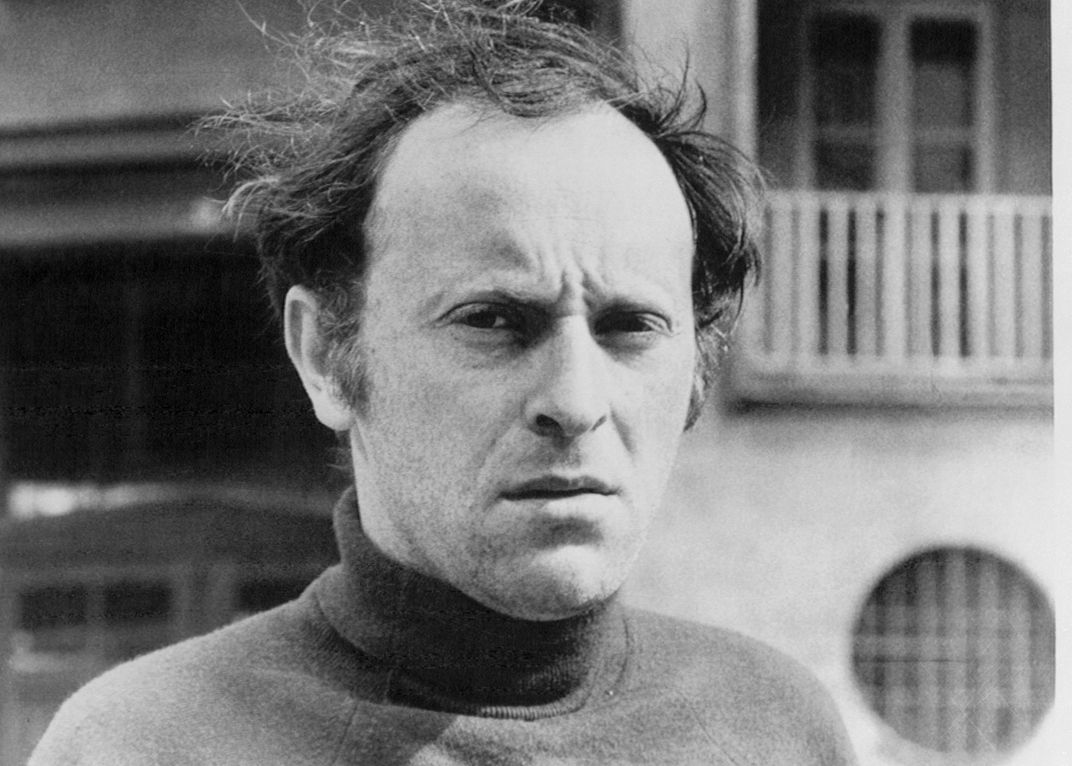

At the time Joseph Brodsky and I met and walked the streets of Venice until dawn, his passion for the city was still young. The dissident-poet had been expelled from his Russian homeland just six years earlier, in 1972. It would be a decade before he would write a collection of mystical meditations on Venice called Watermark, and nearly two decades before the Nobel laureate would be interred in the watery city he once called “my version of Paradise.”

But on this night, Brodsky had just given a reading in a ramshackle movie theater to a group of fellow émigrés and Italian poetry lovers. More than 20 people followed him to a down-at-the-heels trattoria next door where small tables were pushed together to form a long rectangle for him and his admirers.

He and I had met only briefly the previous day, so I was surprised when he invited me to take a seat across from him. My face, he said, reminded him of a friend from his native Leningrad—now again called St. Petersburg—a violinist whose name meant nothing to me. But Brodsky pressed on: “Are you sure that you are not related to him? His face looks very much like yours. He is a very good man and talented too. I miss him.” I replied that I wouldn’t like to disown a relative, particularly a good man and a violinist—perhaps we were cousins.

“That’s the spirit,” Brodsky said. “We are all cousins. And you are indeed my friend’s cousin.”

Alumni of concentration and forced-labor camps are often burdened by memories of hunger, beatings and murders. But when someone at the dinner table asked Brodsky what he recalled from his 18 months of incarceration in the Arctic, he cited the tormented shrubs of the tundra and the interplay of the light refracted by the iceand the pale sun. He also reminisced about “the morbidity of Stalin’s jovial smile” and “the funereal pomp of Moscow’s government edifices.”

There was no hunger this night. We ate mounds of pasta, washed down with red wine. Brodsky eventually signaled to the waiter and paid for his meal in cash. He got up and asked me in English if I wanted to join him fora stroll. “Gladly,” I replied.

“Do you think you can stay awake until dawn?” Brodsky asked me. “You must see the Doges’ Palace in the first light of dawn.”

He resumed talking as soon as we stepped outside, in a language both poetic and abstruse, sometimes speaking in Russian and quickly translating into English. “Venice is eternity itself,” he said, to which I replied that eternity involves a theft of time, which is the work of gods but not mortals.

“Whether by theft or by artistry or by conquest, when it comes to time, Venetians are the world’s greatest experts,” Brodsky parried. “They bested time like no one else.” He again insisted that I summon the strength to walk until the first sunlight painted Piazza San Marco pink. “You must not miss that miracle,” he said.

Although he didn’t know Italian, he felt at home in Venice—and more or less so in Ann Arbor, Michigan; South Hadley, Massachusetts; and New York City. And he frowned on fellow émigrés who didn’t see the appeal of such places of exile. He did not like to hear them complain, after deploring the oppression and confinement of the Soviet system, that freedom offers too many possibilities, many of them disappointing.

He made a face recalling that in the trattoria several of the émigrés quoted Dante, banished from his native Florence: “How salty is the taste of another’s bread, and how hard a path it is to go up and down another’s stairs.” In Russian, Brodsky added, that line sounds better than in English. He also noted, somewhat vaguely, that time is the key to all things.

“Time can be an enemy or a friend,” he said, quickly returning to the subject of the city. He argued that “time is water and the Venetians conquered both by building a city on water, and framed time with their canals. Or tamed time. Or fenced it in. Or caged it.” The city’s engineers and architects were “magicians” and “the wisest of men who figured out how to subdue the sea in order to subdue time.”

We walked through the sleeping town, rarely seeing another passerby. Brodsky was in a good mood except when we passed a church closed down for the night. Then he grumbled like an alcoholic who could not find a tavern open for business.

He declared himself hypnotized by the swirling colors of the marble facades and the stone pavers that imitated water, and he emitted a deep sigh every time we looked down from a bridge. “We pass from one realm of water to another,” he said, and wondered aloud if a Venetian would someday design a bridge that would lead to a star.

For most of our stroll, the poet—who would be awarded the 1987 Nobel Prize in literature—was onstage, delivering monologues. But I had the impression that he was looking for a challenge rather than an endorsement. Some of his comments sounded like a rough draft for a poem or an essay. He repeated himself, revised his statements and often disagreed with what he’d said a few minutes earlier. As a journalist, I noted a common trait: He was a scavenger of images, phrases and ideas. And he poured out words as effortlessly as a fish swims.

Several times in the course of our walk Brodsky called the water “erotic.” After his second or third use of that word, I interrupted: What’s erotic about water?

Brodsky paused, searching for an explanation. His comment did not involve sex, he said, before changing the subject.

In his long essay on Venice titled Watermark, dated 1989 and published as a slim hardcover in 1992, Brodsky expounded further. Gliding in a gondola through the city at night, he found “something distinctly erotic in the noiseless and traceless passage of its lithe body upon the water—much like sliding your palm down the smooth skin of your beloved.” Seeming to pick up where he’d left off more than a decade earlier, he added that he meant “an eroticism not of genders but of elements, a perfect match of their equally lacquered surfaces.” Another detour followed: “The sensation was neutral, almost incestuous, as though you were present as a brother caressed his sister, or vice versa.”

The next image in Watermark was similarly daring. The gondola took him to the Madonna dell’Orto church, closed for the night, just as other churches were when he and I took our stroll. Brodsky was disappointed that he could not visit. He wrote that he wanted to “steal a glance” of Bellini’s famous painting Madonna and Child (stolen in 1993) which offered a detail important for his argument, “an inch-wide interval that separates her left palm from the Child’s sole. That inch—ah, much less!—is what separates love from eroticism. Or perhaps that’s the ultimate in eroticism.”

In 1978, he posed a question to me: What happens to our reflections in the water? He did not have an answer then. In Watermark, he did, asserting that water—whether in the Adriatic or the Atlantic—“stores our reflections for when we are long gone.”

Starting in 1989, Brodsky flew to Venice for nearly every one of his year-end breaks from teaching literature at American colleges. He stayed in cheap hotels or on rare occasions took advantage of a friend’s offer of an empty apartment. But he didn’t bother to add Italian to his repertoire of languages, and wasn’t really interested in assimilating. He vowed never to visit in summer, preferring instead the frigid dampness of Venice in winter. He identified himself as a “Northerner” in Venice and seemed to enjoy feeling like an outsider. “All his life, Joseph had struggled with the consequences of his identification with a group: as a political dissident, as an émigré, as a Jew, as a Russian, as a male, as a cardiac patient, and so on,” Ludmila Shtern wrote in her 2004 book titled Brodsky: A Personal Memoir. “He fiercely defended his right to be what he was, unlike the other members of all the groups to which he was thought to belong. He defended his right to be himself against those who expected conformity and were often hostile to outsiders.”

Brodsky rejected suggestions that he be buried back home in Russia. And yet, at the time of his death by heart attack in 1996, he had left no clear instructions about exactly where he should be interred. Eventually, his wife, Maria Sozzani, decided in favor of Venice’s San Michele cemetery, where Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Diaghilev, members of an earlier generation of Russian exiles, had been buried.

Again he would be an outsider: As a Jew, Brodsky could not join his compatriots in the Eastern Orthodox section of the cemetery. But a place in the Protestant section was secured. Several dozen people showed up for the ceremony. By then, however, it had been discovered that Brodsky’s close neighbor would be Ezra Pound, whom he disliked as a poet and also because of his work as a fascist propagandist. An alternate burial spot a little farther from Pound was found. Among the many flowers arriving from friends and admirers was a giant, horseshoe-shaped wreath of yellow roses from President Boris Yeltsin. The dancer and choreographer Mikhail Baryshnikov, a close friend of Brodsky’s, took the flower arrangement and dismissively tossed it on the grave of Pound, according to one of the mourners and published accounts.

I often recall how in 1978 we waited for the dawn to make its entrance. Brodsky and I, almost the same age, stood at what Dante called “midway in our life’s journey.” We basked in the first rays of the sun rising from the waves of the sea, still as dark as night. The light ricocheted between the waves and the immaculate symmetries of pink marble commissioned by the doges long ago. The poet raised his arms high and bowed, wordlessly saluting the city he had conquered.

Why furs fly here

Excerpt from Watermark by Joseph Brodsky. Copyright © 1992 by Joseph Brodsky.

Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC.

Anyhow, I would never come here in summer, not even at gunpoint. I take heat very poorly; the unmitigated emissions of hydrocarbons and armpits still worse. The shorts-clad herds, especially those neighboring in German, also get on my nerves, because of the inferiority of their—anyone’s—anatomy against that of the columns, pilasters, and statues; because of what their mobility—and all that fuels it—projects versus marble stasis. I guess I am one of those who prefer choice to flux, and stone is always a choice. No matter how well endowed, in this city one’s body, in my view, should be obscured by cloth, if only because it moves. Clothes are perhaps our only approximation of the choice made by marble.

This is, I suppose, an extreme view, but I am a Northerner. In the abstract season life seems more real than at any other, even in the Adriatic, because in winter everything is harder, more stark. Or else take this as propaganda for Venetian boutiques, which do extremely brisk business in low temperatures. In part, of course, this is so because in winter one needs more clothes just to stay warm, not to mention the atavistic urge to shed one’s pelt. Yet no traveler comes here without a spare sweater, jacket, skirt, shirt, slacks, or blouse, since Venice is the sort of city where both the stranger and the native know in advance that one will be on display.

No, bipeds go ape about shopping and dressing up in Venice for reasons not exactly practical; they do so because the city, as it were, challenges them. We all harbor all sorts of misgivings about the flaws in our appearance, anatomy, about the imperfection of our very features. What one sees in this city at every step, turn, perspective, and dead end worsens one’s complexes and insecurities. That’s why one—a woman especially, but a man also—hits the stores as soon as one arrives here, and with a vengeance. The surrounding beauty is such that one instantly conceives of an incoherent animal desire to match it, to be on a par. This has nothing to do with vanity or with the natural surplus of mirrors here, the main one being the very water. It is simply that the city offers bipeds a notion of visual superiority absent in their natural lairs, in their habitual surroundings. That’s why furs fly here, as do suede, silk, linen, wool, and every other kind of fabric. Upon returning home, folks stare in wonderment at what they’ve acquired, knowing full well that there is no place in their native realm to flaunt these acquisitions without scandalizing the natives.

Read more from the Venice Issue of the Smithsonian Journeys Travel Quarterly.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.