A Daring Journey Into the Big Unknown of America’s Largest National Park

If dangling from a rope inside a melting glacier is your idea of a vacation, then come with us to Alaska’s Wrangell-St. Elias

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/00/55/005568be-06c0-4184-ac35-39b4ccd75715/may2018_b08_bigunknown.jpg)

With a trekking pole in one hand and an ice ax in the other, I am naked except for the rigid mountaineering boots on my feet. With all my clothes in my backpack, I cross three braids of the glacier-fed Chitina River in Alaska, stopping to partially recover from the cold on the gravel bars in between. But I know the last ford is going to be the trickiest.

Heavy brown water is pouring through the valley in dozens of plaited streams. The torrents are so forceful there is a roar in the air—water gouging its way through old moraines and rolling boulders along the bottom of the riverbeds. In some places a strand of the flood may be only ten feet wide and one foot deep; in others it is too deep to ford. I consider hiking upstream a few miles and scouting a different crossing. But that will take too long. The bush pilot is arriving in an hour. Besides, I know this route; I crossed here at 5 this morning. It has been a hot day in southeast Alaska, though, and meltwater has been gushing off the glaciers all afternoon.

I step into the water, facing upstream, the toes of my boots pointing into the current like salmon. I shuffle sideways with small steps. I’m hoping the streambed won’t drop and the water won’t rise. Then it does. When the river reaches my waist, I realize I’m in trouble. My trekking pole can’t penetrate the surging current. I’m only 15 feet from the far bank when the freezing water rises to my chest and sweeps me away. I flounder desperately, weighed down by my pack, trying to swim. The pole is ripped out of my hand and I’m frantically clawing and being rushed downstream. In a weird moment of clarity I realize I could drown, and what an absurd death it would be. I don’t know how I keep hold of the ice ax, but I manage to swing it wildly as my head is going under. The pick sinks into the sandy bank and I drag myself out of the river on my hands and knees, coughing up gritty brown water.

I’d come here to Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve to experience its spectacular environment, a vast mountainous terrain dominated by glaciers and riven with furious meltwater. I’d heard that the whole landscape was being profoundly altered by warming temperatures and accelerated melting, but I thought the signs would be more subtle. I didn’t expect to be knocked off my feet and nearly drowned by climate change.

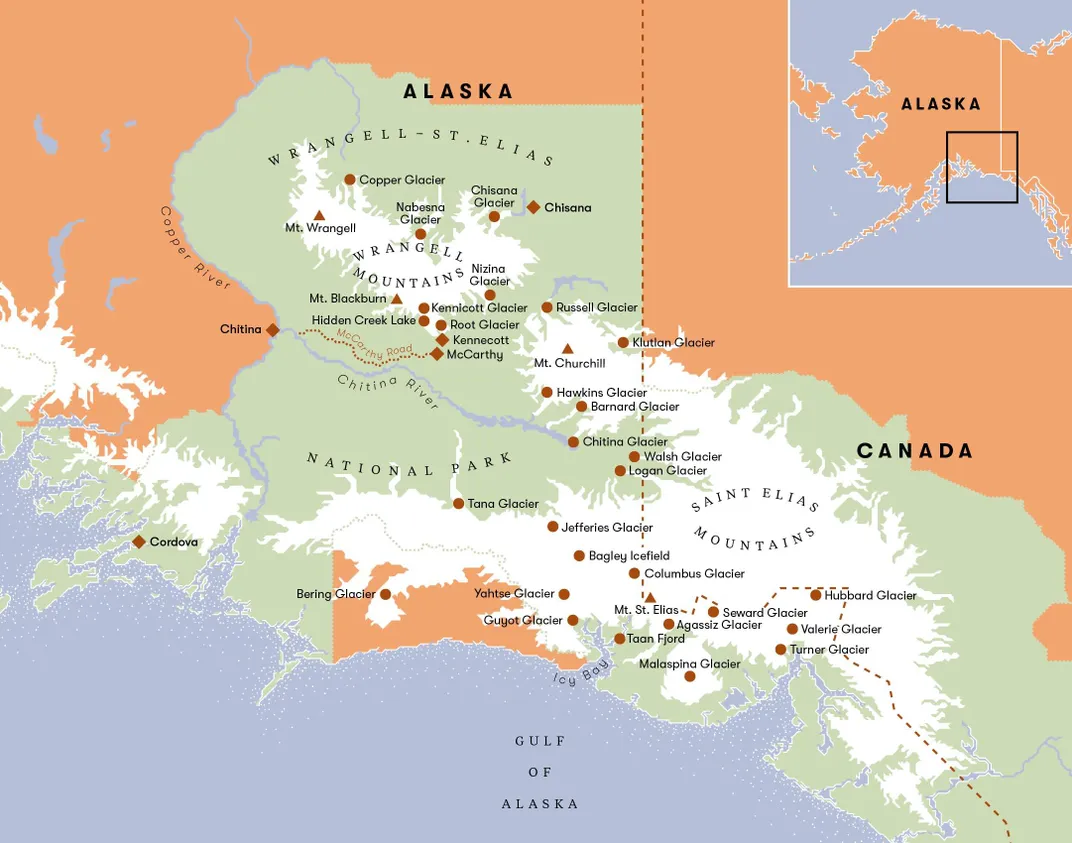

Ecological anxieties aside, there is no other place like Wrangell-St. Elias. The largest national park in the United States, it encompasses 13.2 million acres, an area larger than Yosemite and Yellowstone and all of Switzerland combined. It is remote and not much visited. While Yellowstone gets four million visitors a year, Wrangell-St. Elias last year saw just 70,000, not enough to fill the University of Nebraska football stadium. The wildness is unparalleled. There are some 3,000 glaciers in the park covering more than 7,000 square miles. The Bering Glacier is the nation’s largest. The Malaspina Glacier, the largest piedmont glacier in North America, is larger than Rhode Island. The Bagley Icefield is the largest sheet of ice in the Northern Hemisphere outside the pole.

It’s an astonishing world of ice many thousands of years old, and nobody knows it better than the residents of McCarthy, the fabled bush town deep inside the park. McCarthy is at the end of a road, but you can’t get there by car. After a seven-hour drive from Anchorage, the last 64 miles on shock-destroying washboard, you arrive at a parking lot on the west side of the Kennicott River. The river is deep, fast and about 100 feet wide. Twenty years ago you crossed the river by sitting in a basket and pulling yourself along a mining cable suspended over the raging water. When the cable became too old and sketchy, McCarthy’s 250 or so summer residents, revealing their independent spirit and Alaskan pride, voted against building an automobile bridge. Instead, they erected a footbridge (which is just wide enough for an all-terrain vehicle).

McCarthy has one short main street, all mud, bounded on both ends by bars-cum-restaurants, the Potato and the Golden Saloon. At 61 degrees north latitude, just 5 degrees south of the Arctic Circle, the summer sun in McCarthy hardly sets—it just swirls continuously around the 360-degree horizon, dropping behind the pines between 2 and 4 a.m. Nobody sleeps in the summer. I saw children playing the fiddle at 1 a.m. in the Golden Saloon. People were wandering the one muddy street in broad daylight at 4 in the morning. There was a sign for ATVs nailed to a tree on the main street that read, Slow Please, Free Range Kids and Dogs.

Not long after I arrived, in early July, Kelly Glascott, a lanky, easygoing 24-year-old who works for St. Elias Alpine Guides, invited me to go ice climbing on the Root Glacier with his clients. After a shuttle ride and an hour walk over the rounded white hills of the glacier, we reached a steep wave of ice. The clients all learned the basic crampon and ice-ax techniques and eventually scratched their way up the face. Afterward, Glascott said he had something special to show me. We hiked for 20 minutes before coming upon a giant hole in the glacier, a moulin (pronounced moo-lan, French for “mill”).

“We call it the LeBron Moulin,” Glascott, said, making it rhyme.

A moulin is a nearly vertical shaft formed by meltwater running in a small clear river atop the glacier, disappearing into a crevasse and burrowing a hole straight down to the bottom. The warmer the summer, the more water in the supraglacial rivers, and the bigger the moulins.

“There are moulins all over the glacier every year,” Glascott said.

The mouth of the LeBron Moulin is circular, 20 feet in diameter, with a waterfall on one side. As I peered down into the shaft, Glascott asked me if I’d like to drop into it.

Rigging up several ice screws, he lowered me 200 feet into the hole, so deep I was getting soaked by the ice water pouring down from above. I was in the throat of the beast and felt as if I was about to be swallowed. If we’d had enough rope, I could have been lowered hundreds of feet more, to the glacier’s bedrock bottom. Swinging tools, kicking my crampons, I climbed up and out of the ribbed gullet of blue ice.

Ice climbing inside moulins is a rare and beautiful experience anywhere in the world—in decades of climbing, I’d only done it once before, in Iceland—but it’s a common activity for St. Elias guides, which is what attracts many of them, like Glascott, who is from New York’s Adirondacks.

“I’ve never been anywhere where people have such a deliberate lifestyle,” Glascott said as we ambled back off the glacier. “Everybody in McCarthy chose to be here. The guides, the bush pilots, the park personnel, the other locals—we all love this place.”

People who live here are not your ordinary Americans. They have no fear of bears or moose or moulins, but are terrified of 9-to-5 in a cubicle. They’re free-range humans, eccentric, anarchic, do-it-yourselfers. They gaily refer to themselves as end-of-the-roaders.

Mark Vail—60, bushy white beard, sunburn-red face, wool beret—came here in 1977, caught 35 pounds of king salmon dip-netting, and decided this was the place for him. In 1983, he bought five acres of mosquito-thick spruce sight unseen. “But then I needed to make a grubstake, so I worked as a cook up on the North Slope, base camps and remote lodges.” Vail built his dry cabin—no running water—in 1987 and began living off the land. “Was a challenge to grow anything with only 26 frost-free days a year. Luckily, one fall I canned six cases of moose meat. I lived on less than $2,500 a year for 20 years,” he boasts.

Today Vail barters garden produce such as kale, lettuce, mustard, broccoli, cauliflower and zucchini with the Potato for food. He also works as a naturalist, and told me he’d seen the park change dramatically in the past quarter-century.

“Bottom line, the glacial rivers are growing and the glaciers are retreating and diminishing,” Vail said. “The Kennicott Glacier has retreated over half a mile since I first came here. Ablation has shrunk the height of the glacier by hundreds of feet in the last century.”

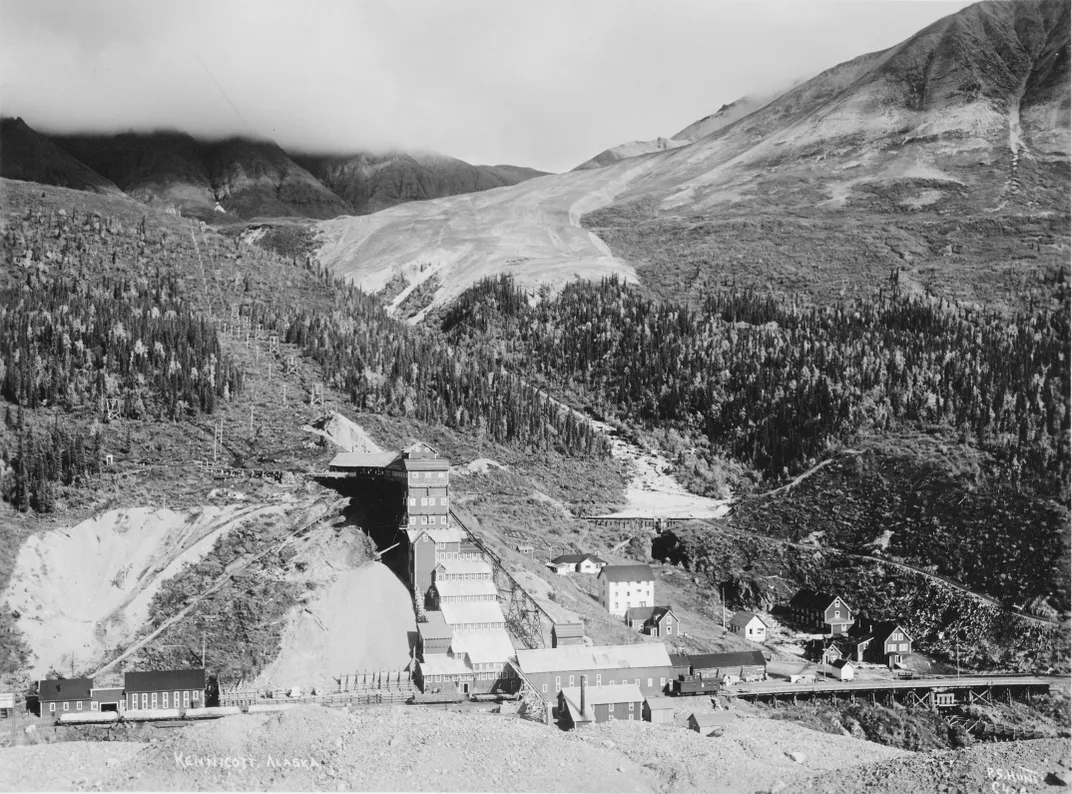

That change was made manifest to me when I climbed up inside the historic 14-story copper mill in the nearby town of Kennecott. In century-old photographs, the Kennicott Glacier looms over the great wooden mill structure like an enormous whale. Today, from the mill you look down onto a shriveled glacier blanketed by stony debris.

**********

The Klondike Gold Rush of 1898 drew prospectors deep into the Wrangell-St.Elias region. But it would be copper, not gold, that panned out. In 1899, Chief Nicolai, of the Chitina Indians, agreed to show these white intruders an outcropping of copper-rich ore in exchange for food. A year later, a prospector by the name of “Tarantula” Jack Smith staked a claim to a steep valley above the Kennicott Glacier, saying, “I’ve got a mountain of copper up there. There’s so much of the stuff sticking out of the ground that it looks like a green sheep pasture in Ireland.” The size of the deposit was so immense, Smith declared it a “bonanza,” a name that stuck.

Construction of a railroad that would connect the Bonanza Mine (and the nearby Jumbo Mine) with the southern coast of Alaska began in 1906. It was a colossal undertaking, exemplary of the industrial vigor and expansionist vision of the early 20th century. “Give me enough dynamite and snoose and I’ll build a road to hell,” bragged Big Mike Heney, the head of the project. Employing over 6,000 men, after five years and $23.5 million (roughly $580 million in today’s money), Heney had carved a 196-mile railway through the mountains from the Alaskan port town of Cordova north to what was now called the Kennecott Mines (a sincere but misspelled tribute to the Smithsonian Institution naturalist Robert Kennicott, who died on an expedition to Alaska in 1866). Everything to build the Bonanza Mine, which is nearly 4,000 feet above Kennecott, was shipped from Seattle to Valdez and later Cordova, then hauled in by horse sleds and by railroad. A thick steel cable almost three miles long supported the trams filled with ore.

The mines, owned by titans of American industry Daniel Guggenheim and J.P. Morgan, paid off handsomely. A single train in 1915 carried out $345,050 worth of copper ore ($8.5 million today). Over the next two decades the Kennecott Mines, one of the richest deposits ever discovered at the time, produced 4.5 million tons of copper ore, worth $200 million (about $3.5 billion today). Among other things, the extracted copper produced wiring that helped electrify all of the lower 48. But the bonanza didn’t last. The price of copper dropped precipitously in the 1930s, and operations at the mine ceased in 1938. Kennecott suddenly became a ghost town.

Kennecott, which sits in the middle of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1986. The National Park Service began stabilizing and restoring the significant buildings in 1998. The general store, the post office and the recreation hall have all been refurbished. The mine opening itself has been dynamited shut, but the immense wooden structures still stick out from the mountainside. The towering 14-story barn-red mill building is one of the tallest wooden structures in North America, and guiding companies provide tours of it. You can still almost feel the sweat and blood of man and beast that was required to build this mine.

At its zenith, 600 miners lived in this company town, eventually digging 70 miles of tunnels in the mountain above the mill. Paid $4.50 a day in 1910, with $1.25 taken out for room and board, most of the miners were from Scandinavia. Kennecott was “dry,” and the miners were not allowed to bring their families to the mining camp. Not surprisingly, another clapboard frontier town sprang up at the turnaround station five miles down the tracks—McCarthy. It had saloons, pool halls and an active red-light district.

McCarthy is still the place to go for a meal and a drink and some music, or to run into a world-class glaciologist who will tell harrowing stories of the fate of an overheated planet.

**********

I met Michael Loso on the planked outdoor patio of the Potato. He was playing clawhammer banjo in a ragtag band and folks were dancing wildly, swinging each other in circles. A 49-year-old glaciologist, Loso is the park’s official physical scientist. A slight, scruffy-bearded former mountaineer, he told me the ominous story of Iceberg Lake, a feature 50 air miles southwest of McCarthy that is no longer there.

Iceberg Lake was on the edge of a western tributary of the Tana Glacier, but in 1999 the lake suddenly vanished. Dammed on its southern end by ice, the water, with persistently warming temperatures, had bored a hole under the ice and escaped through tunnels to emerge ten miles away and empty into the Tana River.

The sudden drainage of a glacier-dammed lake is not uncommon. “Some lakes in Wrangell-St. Elias regularly drain,” Loso said. Hidden Creek Lake, for instance, near McCarthy, drains every summer, pouring millions of gallons through channels in the Kennicott Glacier. The water gushes out the terminus of the Kennicott, causing the Kennicott River to flood, an event called a jokulhlaup—an Icelandic word for a glacial-lake outburst flood. “The Hidden Creek jokulhlaup is so reliable,” said Loso, “it has become one of the biggest parties in McCarthy.”

But the disappearance of Iceberg Lake was different, and unexpected. It left an immense trench in the ground, the ghost of a lake, and it never filled up again. The roughly six-square-mile mudhole turned out to be a glaciological gold mine. The mud, in scientific terms, was laminated lacustrine sediment. Each layer represented one year of accumulation: coarse sands and silts, caused by high runoff during the summer months, sandwiched over fine-grained clay that settled during the long winter months when the lake was covered in ice. The mud laminations, called varves, look like tree rings. Using radiocarbon dating, Loso and his colleagues determined that Iceberg Lake existed continuously for over 1,500 years, from at least A.D. 442 to 1998.

“In the fifth century the planet was colder than it is today,” Loso said, “hence the summer melt was minimal and the varves were correspondingly thin.”

The varves were thicker during warmer periods, for instance from A.D. 1000 to 1250, which is called the Medieval Warming Period by climatologists. Between 1500 and 1850, during the little ice age, the varves were again thinner—less heat means less runoff and thus less lacustrine deposition.

“The varves at Iceberg Lake tell us a very important story,” Loso said. “They’re an archival record that proves there was no catastrophic lake drainage, no jokulhlaup, even during the Medieval Warming Period.” In a scientific paper about the disappearance of Iceberg Lake, Loso was even more emphatic: “Twentieth-century warming is more intense, and accompanied by more extensive glacier retreat, than the Medieval Warming Period or any other time in the last 1,500 years.”

Loso scratched his grizzled face. “When Iceberg Lake vanished, it was a big shock. It was a threshold event, not incremental, but sudden. That’s nature at a tipping point.”

**********

I ran into Spencer Williamson—small, wiry, horn-rimmed glasses—in the Golden Saloon late one Thursday night. The place was packed. Williamson and a buddy were hosting an open-mike jam session. Williamson was pounding the cajón, a box drum from Peru, Loso was working the banjo in a blur of fingers, a couple of youths were ripping fiddles. Patt Garrett, 72, another end-of-the-roader—she sold everything she had in Anchorage to get a lopsided cabin on main street McCarthy—was being twirled around by a tall, bearded Irishman in pink tights and a tutu.

“If you really want to see what’s happening to glaciers,” Loso had told me, “go pack-rafting with Spencer.”

During a break in the music, Williamson, an ebullient, hard-core kayaker, volunteered to take me boating first thing in the morning. Since it was already morning, we were soon walking through the woods with our inflated pack rafts bouncing on our heads.

“I’d guess there are more pack rafts per person in Mc-Carthy than any place in America,” Williamson said.

Weighing only about eight pounds, these ultralight, one-person rafts have completely changed the way adventurers explore all across Alaska, but particularly in Wrangell-St. Elias. Because there are few roads and hundreds of rivers, climbers and backpackers were once confined to small, discrete areas, hemmed in by enormous, unfordable waterways.

Today you can be dropped off with a pack raft, paddle across a river, deflate your boat, load it into your pack, cross a mountain range, climb a peak, then raft another river all the way out.

We dipped our Alpacka rafts into the cold blue Kennicott Glacier Lake. Wearing dry suits, we stretched our spray skirts over the coamings, dug in our kayak paddles and glided away from the forest.

“See that black wall of ice?” Williamson said, pointing his dripping paddle to the far side of the lake, “That’s where we’re going.”

We slid over the water, stroking in unison, moving surprisingly quickly. When I noted how easy this was compared with trying to traverse along the shore, Williamson laughed.

“You got it! Bushwhacking in Alaska is a special kind of misery. With a pack raft, you can just float across a lake or down a river rather than fighting the bushes and the bears.”

Williamson, 26, a guide for Kennicott Wilderness Guides, works May through September. He migrates south in the winter. This snowbird lifestyle is the standard in McCarthy. Mark Vail is one of only a few dozen hearty souls who actually winter over. The other 250 residents—some 50 of whom are guides—abscond from fall to spring, escaping to Anchorage or Arizona or Mexico or Thailand. But they return to tiny McCarthy every summer, like the rufous hummingbird that flies back from Latin America to the same Alaskan flower.

We glided right up beneath the black wall of ice. This was the toe of a 27-mile-long glacier. The big toe, as it turned out. We paddled around the peninsula up into a narrow channel. It was like a slot canyon in ice. Rocks melting off the surface of the glacier plunged 50 feet, splashing like little bombs all around us. Past this channel we paddled through a series of icebergs, moving deeper into the glacier until we entered the final cul-de-sac.

“We couldn’t go this deep just three days ago,” said Williamson excitedly. “The icebergs that blocked our way before have already melted! That’s how fast the ice is vanishing.”

He spotted a hole in the headwall and we paddled over to it, passed through a thin curtain of ceaseless dripping, and entered a low-ceilinged, blue ice cave. I reached up and touched the scalloped ceiling with my bare hands. It felt like cold, wet glass. This ice is thousands of years old. It fell as snow high on 16,390-foot Mount Blackburn, was compressed into ice by the weight of the snow that fell on top of it, and then began slowly bulldozing its way downhill.

We sat quietly in our boats inside the dark ice cave and stared out at the bright world through the line of dripping glacier water. The glacier was melting right before our eyes.

Williamson said, “We are seeing geological time sped up so fast it can be witnessed in human time.”

**********

Wrangell-St. Elias is not like any park in the lower 48 because it is not static. El Capitan in Yosemite will be El Cap for a thousand years. The big ditch of the Grand Canyon won’t look a bit different in A.D. 3000. Barring some tectonic catastrophe, Yellowstone will be burbling along for centuries. But Wrangell-St. Elias, because it is a landscape of moving, melting glaciers, is morphing every minute. It will be a different park ten years from now.

According to a recent scientific report, between 1962 and 2006, glaciers melting in Alaska lost more than 440 cubic miles of water—nearly four times the volume of Lake Erie. “Ice shelves breaking off in Antarctica get a lot of press,” says Robert Anderson, a geologist at the Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research at the University of Colorado, “but these melting Alaskan glaciers matter.” Anderson has been studying glaciers in Wrangell-St. Elias for two decades. “What is rarely recognized is that surface glaciers, like those in Alaska, are probably contributing almost 50 percent of the water to sea-level rise.” NASA reports that the current sea-level rise is 3.4 millimeters a year, and increasing.

“One of the most startling, and devastating, consequences of this rapid melting of the ice was the Icy Bay landslide,” says Anderson.

Hiking Alaska's Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve: From Day Hikes To Backcountry Treks (Regional Hiking Series)

Six times the size of Yellowstone National Park, Wrangell-St. Elias welcomes 40,000 visitors every year, and each of them will maximize the visit with this all-new guidebook.

The Tyndall Glacier, on the southern coast of Alaska, has been retreating so quickly that it is leaving behind steep, unsupported walls of rock and dirt. On October 17, 2015, the largest landslide in North America in 38 years crashed down in the Taan Fjord. The landslide was so enormous it was detected by seismologists at Columbia University in New York. Over 200 million tons of rock slid into the Taan Fjord in about 60 seconds. This, in turn, created a tsunami that was initially 630 feet high and roared down the fjord, obliterating virtually everything in its path even as it diminished to some 50 feet after ten miles.

“Alder trees 500 feet up the hillsides were ripped away,” Anderson says. “Glacial ice is buttressing the mountainsides in Alaska, and when this ice retreats, there is a good chance for catastrophic landslides.” In other ranges, such as the Alps and the Himalaya, he says, the melting of “ground ice,” which sort of glues rock masses to mountainsides, can release enormous landslides into populated valleys, with devastating consequences.

“For most humans, climate change is an abstraction,” Loso says when I meet him in his office, which is down a long, dark, heavily beamed mine building in Kennecott. “It’s moving so slowly as to be basically imperceptible. But not here! Here glaciers tell the story. They’re like the world’s giant, centuries-old thermometers.”

**********

Before leaving Wrangell-St. Elias, on my last night in McCarthy, I am in the Potato, typing up notes, when someone runs in shouting, “The river’s rising!”

This can portend only one event: the Hidden Creek Lake jokulhlaup. Dammed by a wall of ice ten miles up the Kennicott Glacier, Hidden Creek Lake has once again bored beneath the glacier and is draining.

The whole town goes out to the walking bridge. Sure enough, the river is raging, a full five feet higher than just a few hours earlier. It’s a party, a celebration, like Christmas or Halloween. The bridge is packed with revelers hooting and toasting this most dynamic of glacial events. A guide named Paige Bedwell gives me a hug and hands me a beer. “Happy Jokulhlaup!”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.