The Old-World Charm of Venice’s Windy Sister City

On the Adriatic island of Korčula, where Venice once ruled, ancient habits and attitudes persist—including a tendency toward blissful indolence

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ea/eb/eaeb48ea-80d9-47b6-ac4e-5b9921cda93d/sqj_1510_venice_korcula_01.jpg)

For me, it is the most beautiful view in the world. I am sitting on my rooftop balcony, looking through a tunnel of sea, mountains and sky that connects this former Venetian town to her ancient metropolis, the Serenissima. It is late afternoon. The northwest wind known as the maestral is whipping down the channel that separates us from the Croatian mainland. Windsurfers, kite surfers and sailboats dart back and forth across the milewide expanse of water. Below me are the ocher rooftops of Korčula (pronounced KOR-chu-la), perched on a rocky promontory surrounded by the translucent sea.

In a couple of hours, the sun will go down over the mountains, creating a seascape of musty pinks, blues and greens. In my mind’s eye, I follow the age-old trade route along the Dalmatian coast to Venice at the head of the Adriatic, nearly 400 miles away. It is easy to imagine Venetian galleys and sailing ships on patrol beneath the ramparts of Korčula, ready to do battle against rival city-states like Ragusa and Genoa, the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary pirates of North Africa.

I have been coming to Korčula—or Curzola, as it was known in Venetian times—for more than four decades, ever since I was a child. It is a place that still has the power to take my breath away, particularly in the quiet of the early morning and evening, when the polished white stones of the Old Town seem to float above the water. With its cathedral and miniature piazzetta, dreamy courtyards and romantic balconies, and elaborately carved Gothic windows and family crests, Korčula is “a perfect specimen of a Venetian town,” in the phrase of a 19th-century English historian, Edward Augustus Freeman.

More than three centuries have passed since the “Most Serene” Republic ruled this stretch of Dalmatian coastline, but her influence is evident everywhere, from the winged lion that greets visitors at the ceremonial entrance to the town to the hearty fish soup known as brodet to the “gondola” references in Korčulan folk songs.

The extraordinarily rich Korčulan dialect is sprinkled not only with Italian words like pomodoro (tomato) and aiuto (help) but also specifically Venetian words like gratar (to fish) and tecia (cooking pan) that have nothing in common with either Croatian or Italian.

The legacy of more than 400 years of Venetian rule can also be felt in the habits and mind-set of the Korčulans. “Every Korčulan imagines himself to be descended from a noble Venetian family,” says my friend Ivo Tedeschi. “We feel that we are at the center of our own little universe.” Families with Italian names like Arneri and Boschi and Depolo have been prominent in Korčula since Venetian times. As befits a place that was sometimes called the “arsenal of Venice,” Korčula still boasts its own shipyard, albeit one that has fallen on hard times with the economic crisis in Croatia.

Contributing to the sense of crumbling grandeur is the location of Korčula at the crossroads of geography and history. This was where West met East—the intersection of Roman Catholic, Orthodox and Islamic civilizations. For the most part, these worlds have lived in harmony with one another, but occasionally they have clashed, with disastrous consequences, as happened in the bloody breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. My house overlooks the narrowest point of the Pelješac canal, which straddled the dividing line between the western and eastern parts of the Roman Empire—Rome and Byzantium—and marked the seaborne approaches to the Serenissima.

Korčula changed hands several times during the Napoleonic Wars, from the French to the British and finally to the Austrians. Since the early 19th century, it has belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany, Communist Yugoslavia and the Republic of Croatia. Each shift in power was accompanied by the destruction of the symbols of the previous regime and the wholesale renaming of streets, leaving people confused about their own address.

My friend Gaella Gottwald points out a frieze of a defaced winged lion, sitting forlornly next to the town hall. “The lion was the symbol of Venetian power,” she explains. “When the Communists took over after World War II, they destroyed anything that reminded the people of Italian rule.” A few winged lions survived high up on the city walls, but most were removed and replaced by the red Partisan star and portraits of Marshal Tito. Similarly, after the fall of communism in 1991, most of the Partisan stars were replaced with the checkerboard emblem of independent Croatia. The Josip Broz Tito Harbor was renamed the Franjo Tudjman Harbor, after Croatia’s new nationalist leader.

Medieval Air-Conditioning

Most of what I know about the winds of Korčula I have learned from Rosario Vilović, a retired sea captain who lives up our street. Each wind has its own name and distinct personality. “The maestral blows in the afternoon in summer,” he says, pointing to the northwest, toward Venice. “It is a warm, dry, very refreshing wind.” His brow thickens as he gestures to the northeast, over the forbidding limestone mountains of the Pelješac Peninsula. “The bora is our strongest and most destructive wind. When a bora threatens, we run inside and close all our shutters and windows.” He turns toward the south. “The jugo is humid and wet and brings a lot of rain.” And so he continues, around all the points of the compass.

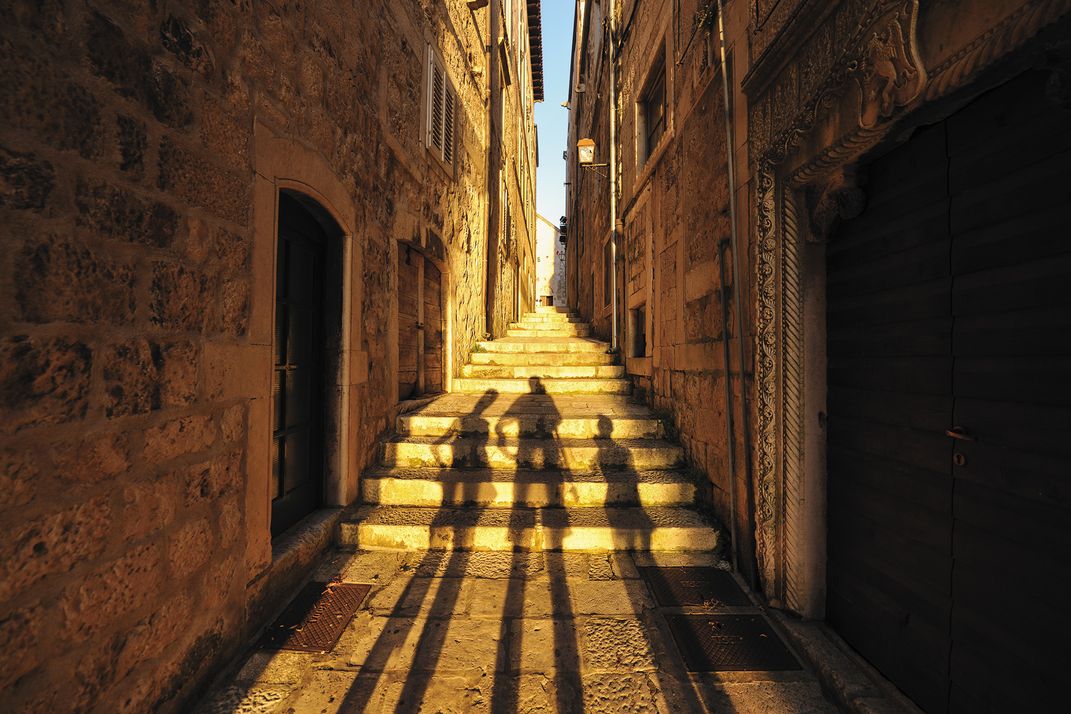

Winds are to Korčula as canals are to Venice, shaping her geography, character and destiny. When the city fathers laid out the town at least 800 years ago, they created a medieval air-conditioning system based on wind circulation. On the western side of the town the streets are all straight, open to the maestral. On our side of town, facing the Pelješac, the streets are crooked, to keep the bora out.

In Korčula, horses and carriages “are as impossible as at Venice itself, though not for the same reason,” wrote Freeman in his 1881 book, Sketches From the Subject and Neighbour Lands of Venice, which remains one of the best guidebooks to the Dalmatian coast. “Curzola does not float upon the waters, it soars above them.” Viewed from above, the island resembles the crumpled skeleton of a fish, straight on one side but crooked on the other. A narrow spine down the middle serves as the main street, centered on the cathedral and its miniature square, climbing over the top of the humpbacked peninsula. The streets are steep and narrow: There is barely room for two pedestrians to pass each other without touching.

One result of Korčula’s unique wind circulation system is the orientation of the town toward the maestral and therefore toward Venice. The western side of the town is open and inviting, with a seafront promenade, harbor and hotel. The eastern side is fortified, against both the bora and the Moor. It is a layout that reflects the geopolitical orientation of Korčula toward the West, away from the Slavic world, Islam and the Orient.

The battle between East and West is echoed in a traditional sword dance known as the Moreška, which used to be performed throughout the Mediterranean but seems to have survived only in Korčula. The dance is a morality tale pitting the army of the Red King (Christians) against the army of the Black King (Moors), over the honor of a fair Korčulan lady. Sparks fly (literally) from the clashing swords, but needless to say, the fix is in, and the favored team emerges triumphant every time.

Given Korčula’s strategic location, it is hardly surprising that the island has been the prey of numerous foreign navies. The Genoese won a great sea battle over the Venetians within sight of my house in 1298, leading to the capture of the Venetian explorer Marco Polo. An Ottoman fleet led by the feared corsair Uluz Ali passed by here in 1571. According to Korčula legend, the Venetians fled, leaving the island to be defended by the locals, mainly women who lined the city walls clad in military attire. The show was sufficiently impressive to dissuade the Turks from attacking Korčula; they sailed away to pillage the neighboring island of Hvar instead. (An alternative story is that the Turkish fleet was dispersed by a storm.) In recognition of its devotion to Christendom, Korčula earned the title “Fidelissima” (Most Faithful One) from the pope.

The winds and the sea have also endowed Korčula with a long line of distinguished seafarers. The most prominent of them, according to the Korčulans, is Marco Polo himself, whose celebrated travel book gave Europeans their first insight into the customs and history of China. In truth, Korčula’s claim to be Marco Polo’s birthplace is tenuous, but no more so than the claims of others, such as Šibenik (farther up the Dalmatian coast) and Venice itself. It rests mainly on oral tradition and the fact that a “De Polo” family has been living in Korčula for centuries. The Marco Polo connection has proved a boon to the local tourist industry, spawning a “Marco Polo house,” half a dozen “Marco Polo shops” and “museums,” “Marco Polo ice cream,” and several competing Marco Polo impersonators.

Collecting absurd Marco Polo claims has become a pastime of Korčula’s foreign residents. My personal favorites: “Marco Polo brought these noodles back from China” (on the menu of a local restaurant) and “Marco Polo found great food and love in this house” (sign outside another restaurant). A few years ago a friend of ours packaged a bulbous piece of plaster in a cardboard box and labeled it “Marco Polo’s Nose—an Original Souvenir from Korčula.” It was an instant hit with locals and tourists.

A different state of being

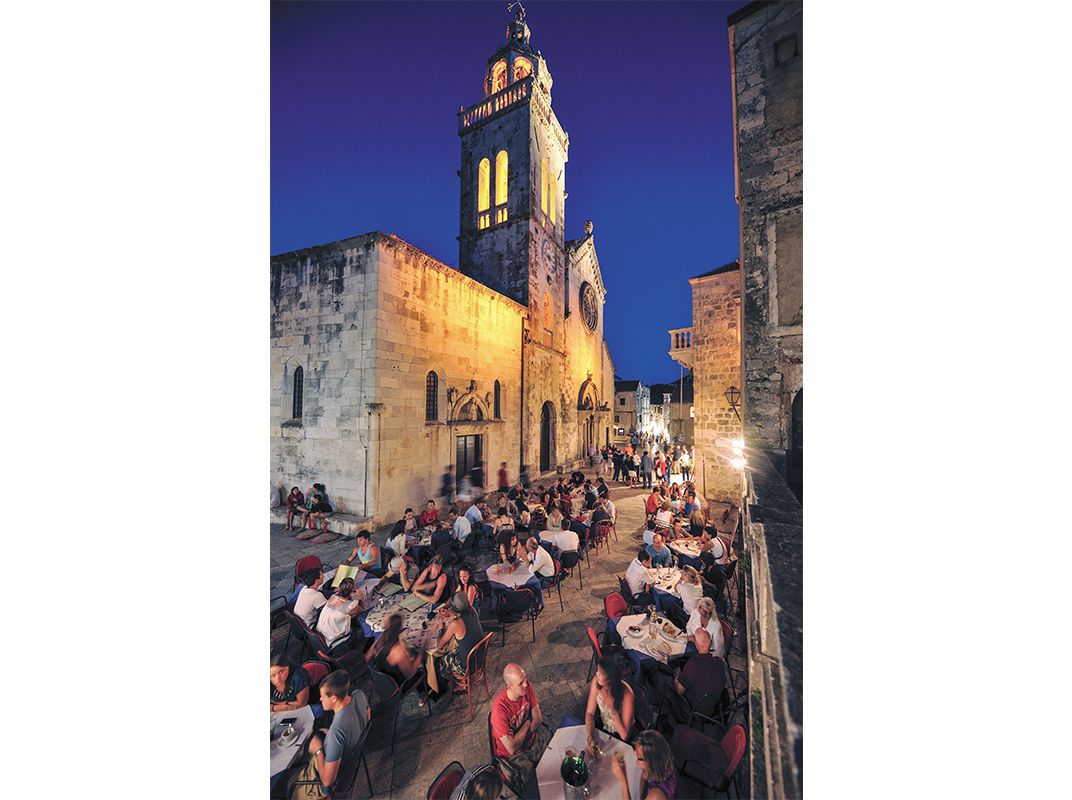

One of the qualities that Korčula shares with Venice is a sense of living on the edge of disaster. Venetians face floods, storms and the demands of modern tourism as threats to their noble city. In the case of Korčula, it is the onslaught of vacationers in the summer months that fuels concern over the town’s fragile infrastructure. Megayachts with names like Will Power and Eclipse and Sovereign maneuver for docking space in the harbor. A 15th-century tower that was once part of Korčula’s defenses against the Turks becomes a cocktail bar selling overpriced mojitos to raucous Italians and Australians.

The most obvious evidence of the imbalance between tourism and infrastructure is the unpleasant odor of raw sewage that wafts over parts of the town on hot summer days, particularly when the breeze is blowing in the wrong direction. The Venetian-built sewage canals, known as kaniželas (from the Venetian canisela), have become clogged with the detritus of unauthorized construction and the waste of the Marco Polo-themed restaurants. Short of ripping out the medieval guts of the town and tunneling deep under the cobbled alleyways, there is no obvious solution.

Yet Korčulans are the first to admit that they lack the moneymaking dynamism of their neighbors in Hvar, who have turned their island into the showcase of the Croatian tourist industry. In Korčula, tourists tend to be viewed as a necessary evil. The Hvar city fathers considered silencing the church bells after foreign visitors complained about the noise; in Korčula, the bells are as much a part of the landscape as the sea and the air, and continue to peal at all times of the day and night.

For those of us who consider ourselves adopted Korčulans, the summer crowds and occasional unpleasant smells are a small price to pay for the privilege of living in a magical, almost timeless place. The Croatian tourist slogan “the Mediterranean as it once was” seems an exaggeration on other parts of the Dalmatian coast but encapsulates the laid-back pace of life in Korčula. It is a world of lazy afternoon siestas, invigorating swims in the crystal clear Adriatic, scents of wild mint and rosemary and lavender, sounds of crickets singing in the pine trees, tastes of succulent tomatoes and fresh grilled fish, all washed down with glasses of Pošip (pronounced POSH-ip], the dry white wine that is native to the island.

There is a Dalmatian expression—fjaka, deriving from the Italian word fiacca—that sums up this blissful existence. The closest translation would be “indolence” or “relaxation,” but it has much subtler connotations. “Fjaka is a philosophy, a way of life,” explains my neighbor Jasna Peručić, a Croatian American who works as a hard-charging New York real estate agent when she is not relaxing in Korčula. “It means more than simply doing nothing. It is a state of well-being in which you are perfectly content.”

To fully achieve this state, however, requires a reorientation of the mind: The locals also use fjaka as a one-word explanation for the impossibility of finding an electrician or a plumber—or getting very much done at all—particularly when the humid south wind is blowing in the dog days of summer.

Like other foreigners who fall in love with Korčula, I have come to understand that true relaxation—fjaka—comes from adapting yourself to the rhythms and habits of your adopted town. Every summer I arrive in Korčula with ambitious plans to explore more of the Dalmatian coast, go for long hikes or bike rides, improve the house, or work on an unfinished book. Almost invariably, these plans fall through. Instead I am perfectly content with the daily routine of shopping for fish and pomodori, cooking, eating, talking and sleeping.

The flip side of fjaka is occasional bursts of almost manic energy. A decade or so ago, my neighbors invented a new festival known as “Half New Year,” which is celebrated on June 30. For one hilarious evening, villagers from all over the island compete with one another to devise the most outrageous form of costume, parading around the town in rival teams of prancing minstrels, dancing Hitlers and little green men from Mars. Marching bands lead the revelers, young and old, on a tour of the ancient battlements. And then, as suddenly as it has awakened, the town falls back asleep.

When I sail away from Korčula at the end of the summer, watching the white stones of the old town recede into the watery distance, I feel a stab of melancholy. As in Venice, the feeling of loss is enhanced by the sense that all this beauty could simply disappear. It is as if I am seeing an old friend for the last time. But then I remember that Korčula—like Venice—has survived wars and earthquakes, fires and plagues, Fascism and Communism, Ottoman navies and armies of modern-day tourists.

My guess is that the Fidelissima, like the Serenissima, will still be casting her spell for many centuries to come.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.