In Bolivia’s High-Altitude Capital, Indigenous Traditions Thrive Once Again

Among sacred mountains, in a city where spells are cast and potions brewed, the otherworldly is everyday

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d5/c4/d5c4b07c-55e8-4439-a0e9-5997831d699f/la-paz-bolivia-ceremony-desert.jpg)

For most of the seven years I lived in La Paz, my home was a small stucco cottage pressed into a hillside. The cement floors were cold, and the second-story roof was corrugated metal, which made rain and hail such a racket that storms often sent me downstairs. But the views more than compensated for the hassles. When I moved in, I painted the bedroom walls heron-egg blue and put the mattress so close to the window I could press my nose against the glass. At night I fell asleep watching the city lights knit up into the stars, and in the morning I woke to a panoramic view of Illimani, the 21,000-foot peak that sits on its haunches keeping watch over Bolivia’s capital. It was like living in the sky.

Once you get used to all that altitude, La Paz is best explored on foot. Walking allows you to revel in the staggering vistas while dialing into an intimate world of ritual and ceremony, whether inhaling the sweet green aroma of burning herbs along a well-worn path or coming upon a procession celebrating the saints who safeguard each neighborhood. One of my closest friends, Oscar Vega, lived a ten-minute walk from my house. Oscar is a sociologist and writer with dense gray hair, freckled cheeks, and thick eyeglasses. Every few days we had a long, late lunch or coffee, and I liked nothing better than going to meet him, hustling along steep cobblestone streets that cascade down into the main avenue known as the Prado, hoping to imitate the elegant shuffle-jog used by many paceños as they negotiate the pitched terrain. Men in leather jackets and pleated trousers, women in full skirts or 1980s-style pantsuits, or teenagers in Converse sneakers; they all seemed to understand this common way of moving. In La Paz, life happens on a vertical plane. Negotiating the city is always spoken of in terms of up and down because it’s not just surrounded by mountains: It is mountains.

The most important things to consider in La Paz are the geography and the fact that its identity is closely tied to indigenous Aymara culture. “The mountains are everywhere,” said Oscar. “But it’s not just that they’re there; it’s also the way we’re influenced by the indigenous notion that these mountains have spirits—apus—and that those spirits watch over everything that lives nearby.”

Oscar is also passionate about seeing the city on foot. Ten years ago, when we became friends, he told me about Jaime Sáenz, the poet-flaneur of La Paz, and Sáenz’s book, Imágenes Paceñas. It’s a strange, unapologetic love letter to the city, a catalog of streets and landmarks and working-class people, punctuated by blurred photos with captions that resemble Zen koans. The very first

entry is a silhouette of Illimani—the mountain—and after it, a page with a few sentences:

Illimani is simply there—it is not something that is seen… / The mountain is a presence.

Those lines ring especially true during the winter solstice, when Illimani virtually presides over the many celebrations. In the Southern Hemisphere, the day usually falls on June 21, which also marks the New Year in the tradition of the Aymara people, for whom the New Year is a deeply felt holiday. The celebration hinges on welcoming the first rays of the sun—and while you can do so anywhere the sun shines, the belief is that the bigger the view of the mountains and sky, the more meaningful the welcome.

Most years I joined friends to celebrate in Tupac Katari Plaza, a tiny square up in El Alto that looks down into La Paz, with an unobstructed view of all the biggest peaks: sentry-like Illimani and many others. Every year, about a dozen people showed up early, staying warm by sipping coffee and tea and Singani, Bolivia’s potent national spirit, while whispering and pacing in the dark. And every year, I would be sure that the turnout would be equally understated, only to watch as, just before sunrise, sudden and overwhelming crowds gathered in the plaza. Each person’s elbows seemed to be quietly pressing into someone else’s ribs, everyone charged with anticipation that something sacred was about to happen. As the sun lifted over the Andes, we all raised our hands to receive its first rays, heads ever so slightly bowed. As if the sun—and the mountains—were something to be felt rather than seen.

**********

When I told Oscar I wanted to learn more about the rituals I’d seen around La Paz, he sent me to talk to Milton Eyzaguirre, the head of the education department of Bolivia’s ethnographic museum—known as MUSEF. The first thing Milton did was to remind me that it wasn’t always so easy to practice indigenous traditions in public.

“When I was growing up, all of our rituals were prohibited. People treated you terribly if you did anything that could be perceived as indigenous,” Milton said. Milton has sharp, bright eyes and a neatly trimmed goatee. His office is tucked away inside the museum, just a few blocks away from the Plaza Murillo, where the congress building and presidential palace are located.

“We were losing our roots. We lived in the city, and we had very little relationship to rural life or the rituals that had come out of it. We were all being taught not to look to the Andes but to the West. If you still identified with the mountains, or with Andean culture in general, you faced serious discrimination.”

Milton told me that even though his parents are Aymara and Quechua, by the time he was born, they’d already stopped celebrating most of their traditions. When he explored Andean culture as a teenager—and eventually decided to become an anthropologist—it all stemmed from a desire to question the latent repression he saw happening to his own family, and to indigenous Bolivians in general.

I immediately thought of Bolivia’s current president, Evo Morales, an Aymara coca farmer first elected in 2005. Over the years, I’ve interviewed Morales a handful of times—but I most remember the first interview, a few weeks after he’d been sworn in. At a question about what it was like to be from an indigenous family, he thought long and hard, then told a story about being ridiculed as a kid when he moved to the city from the countryside. Since Morales spent most of his early childhood speaking Aymara, his Spanish was thickly accented, and he said both his classmates and his teachers made fun of that accent; that they berated him for being indigenous—even though many of them were indigenous themselves. The experience left such an impression that he mostly stopped speaking Aymara. Now, he said, he had trouble holding a conversation in his first language. Morales paused again, then gestured outside the window to the Plaza Murillo, his face briefly tight and fragile. Fifty years earlier, he said, his mother hadn’t been allowed to walk across that plaza because she was indigenous. The simple act of walking across a public space was prohibited for the country’s majority.

The last time I spoke with Morales was at an event several years later, and it was just a standard hello and handshake. The event, however, was quite remarkable. It was a llama sacrifice at a smelter owned by the Bolivian state. Several indigenous priests known as yatiris had just overseen an elaborate ceremony meant to offer thanks to the Earth—in the Andes, a spirit known as Pachamama—and to bring good fortune to the workers, most of whom were also indigenous. In Bolivia, there are many different types of yatiris; depending on the specialty, a yatiri might preside over blessings, read the future in coca leaves, help cure illnesses according to Andean remedies, or even cast powerful spells. Whatever you thought of Morales’s politics, it was clear that a huge cultural shift was taking place.

“Everything Andean has a new value,” said Eyzaguirre, referring to the years since Morales has been in office. “Now we’re all proud to look to the Andes again. Even a lot of people that aren’t indigenous.”

**********

Geraldine O’Brien Sáenz is an artist and a distant relative of Jaime Sáenz. Though she spent a brief stint in Colorado as a teenager and has an American father, she’s spent most of her life in La Paz and is a keen observer of the place—and of the small rituals that have gradually been folded into popular culture.

“Like when you pachamamear,” she said, referring to the way that most residents of La Paz spill out the first sip of alcohol onto the ground when drinking with friends, as a show of gratitude to the Earth. “It’s not mandatory, of course, but it’s common. Especially if you’re out drinking in the street, which is a ritual of its own.”

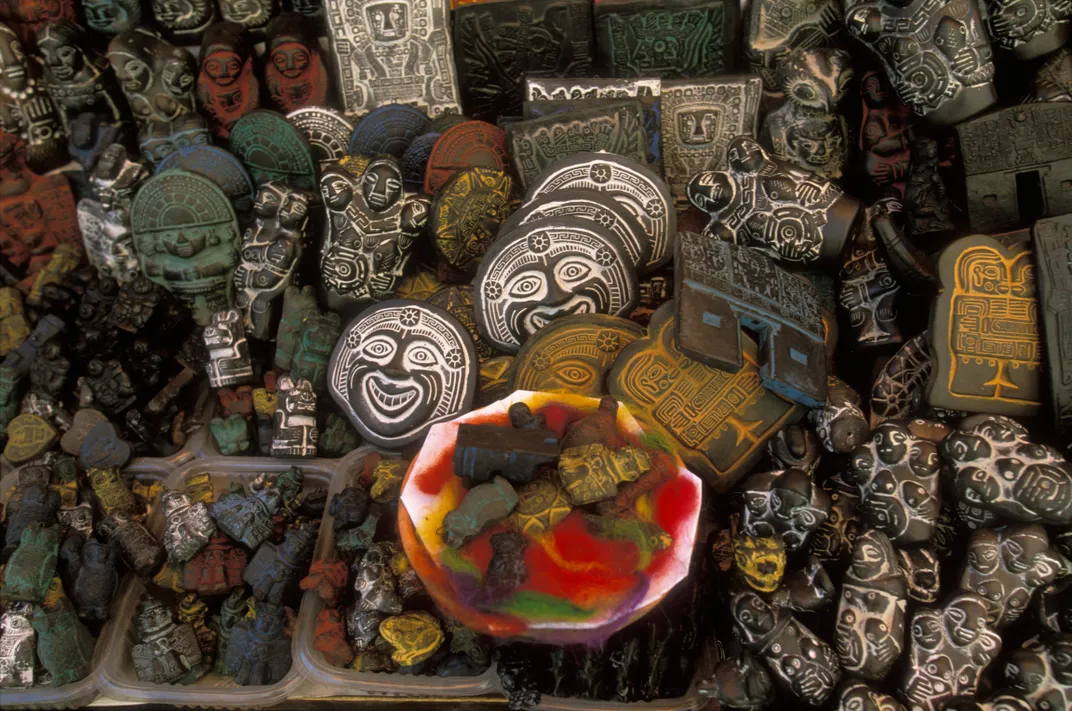

She also participates in Alasitas, the festival in January when people collect dollhouse-size miniatures of everything they hope to have in the coming year, from cars and houses to diplomas, plane tickets, sewing machines and construction equipment. All items must be properly blessed by noon on the holiday, which causes midday traffic jams every year as people rush to make the deadline.

Geraldine admitted that she observes Alasitas mostly because of her younger sister, Michelle, who has a penchant for it. For the blessing to really work, said Geraldine, you can’t buy anything for yourself; instead, you must receive the miniatures as gifts. So Michelle and Geraldine go out, buy each other objects representing their wishes and pay to have an on-site yatiri bless everything while dousing it in smoke, flower petals and alcohol. The blessing is known as a ch’alla.

“So now I have like 25 years’ worth of Alasitas stuff sitting in my house,” said Geraldine. “They’re actually rotting because of the ch’alla, all that wine and flower petals sitting in a plastic bag. But there’s no way I’d throw it out. That’s bad luck.”

This fear of repercussions underpins many rituals. Miners make offerings to a character known as El Tío, who is the god of the mine, because they want to strike it rich—and because they want to keep El Tío from getting angry and causing a tunnel to cave in on them or a misplaced stick of dynamite to take off someone’s hand. Anyone doing construction makes an offering to Pachamama, first when breaking ground and again when pouring the foundation, to ensure that the building turns out well—and also to keep people from getting hurt or killed in the process of putting it up.

All those I spoke to, whether they follow indigenous traditions or not, had a cautionary tale about something bad happening after someone failed to respect rituals. Oscar talked about having to call in a yatiri for a blessing at his office, to protect some colleagues frightened by a co-worker who’d started studying black magic. Geraldine told me about an apartment building that collapsed—perhaps because a llama fetus hadn’t been buried as it should have been in the foundation. She recalled the Bolivian film Elephant Cemetery, which references an urban legend that some buildings actually require a human sacrifice. And Milton Eyzaguirre related how during one phase of construction of the museum where he works, four workers died on the job. He directly attributes it to the lack of a proper offering made before the start of construction.

“In instances where there’s not a proper ch’alla, people get hurt. I mean, you’re opening up the Earth. I think it’s prudent to ask permission. Because if you don’t, the spirits in the house or in the spot where you’re building—they may get jealous. Which will make things go very, very badly.”

“They couldn’t kill off the mountains, so building on them was the next best thing,” said Milton as he described the arrival of the Spanish. He told me that once the Spanish realized they couldn’t eliminate the Andean gods—they were the Earth and mountains, after all—they decided to erect churches on top of the spots that were most important to Andean religion.

He added that urban life itself also changed the way people practice rituals of rural origin. For instance, in the countryside people traditionally danced in circles and up into the mountains as an offering to their community and to the Earth. But in La Paz, he said, most people now dance downward in typical parade formation, orienting themselves along the main avenues that lead down

toward the city center.

Still, compared with most other capital cities in the Americas, La Paz retains a distinctly rural identity, and the way people interact with the city on foot is part of that. “Sure, people are starting to take taxis or buses more and more, but we all still go out on foot, even if it’s just strolling down the Prado or going to the corner for bread,” said Oscar. Like many paceños, he goes out early each morning to buy fresh marraquetas. The rustic, dense rolls are usually sold on the street in enormous baskets. They’re best nibbled plain, warm—ideally, while walking around on a damp morning.

One afternoon in late winter, when Oscar said he was feeling restless, we decided we’d walk up into the mountains the following day. In the morning we met at sunrise, picked up coffee and marraquetas, and scaled Calle Mexico to the Club Andino, a local mountaineering organization. The Club Andino sometimes offers a cheap shuttle from downtown La Paz to Chacaltaya, a mountain peak atop a former glacier deep in the Andes, about an hour and a half from the city center.

We folded ourselves into a back corner of a large van with three or four rows of seats, the same kind of van that runs up and down the Prado with someone hanging from the window calling out routes. Oscar and I looked out the windows at the high-altitude plains. He mentioned how his former partner—a Colombian woman named Olga with whom he has two daughters and whom he still considers a close friend—couldn’t stand the geography of La Paz.

“I think this landscape is just too much for some people.” He said it pleasantly, as if the idea were puzzling to him; as if the landscape in question were not immense scrubby plains flanked by barren, even more immense mountains, all of it under a flat and penetratingly bright sky. I fully empathize with Olga’s feelings about the intensity of the high Andes, yet I’ve come to love this geography. After almost a decade spent living there, I still get weepy each time I fly in and out of La Paz. The environment is stark, and harsh—but also stunning, the sort of landscape that puts you in your place, in the very best way possible.

Once at Chacaltaya, we struck out into the mountains on our own. While I could pick out the well-known peaks I saw from my bedroom window or while wandering in the city, now there was a sea of dramatic topography I did not recognize. Luckily, all I had to do was follow Oscar, who has walked up these mountains since he was a teenager. No trail, no map, no compass. Only the orientation of the mountains.

Within a few hours, we were approaching a high pass near an abandoned mine, the sort that a few men might haphazardly dig and dynamite in a bid to earn a little money. A smell like paint fumes came out of the mouth of the mine, and we speculated about what kind of god might live inside. After pulling ourselves up a three-sided shaft for moving tools and materials along the almost vertical incline, we reached the summit of that particular mountain and stood on a ledge looking out over other mountains stretching to the horizon. I realized I might faint, and said so. Oscar just laughed and said he wasn’t surprised. We’d reached about 15,000 feet. He motioned to sit, our feet dangling over the ledge into nothing, then handed me pieces of chocolate meant to help with lightheadedness, while he smoked a cigarette. We continued, descending several hundred feet in altitude, enough for me to spend breath on conversation again. For Oscar, however, oxygen never seemed to be an issue. He had been blithely smoking since we got out of the van at the dying glacier.

At the end of the day, we returned to a lagoon where earlier that morning we’d noticed two Aymara families preparing chuño: freeze-dried potatoes made by exposing the tubers to the cold night air, then soaking them in a pool of frigid water, stomping the water out, and letting them dry in the sun. Now the family was packing up. We said hello and talked for a moment about the chuño, then hiked to the road, where we waited till a truck pulled over. There were already two families of farmers in the open-roofed cargo space. We exchanged greetings, then all sat on our heels in silence, listening to the roar of the wind and watching lichen-covered cliffs zoom overhead as we descended back into La Paz.

Eventually the cliffs were replaced by cement-and-glass buildings, and soon after, the truck stopped. We could make out the sound of brass bands. Chuquiaguillo, one of the neighborhoods on the northern slopes of the city, was celebrating its patron saint, with a distinctly La Paz mix of Roman Catholic iconography and indigenous ceremony. Oscar and I climbed out of the truck and jogged through the crowd. We made our way through packs of dancers in sequins and ribbons, musicians in slick tailored suits, women peddling skewers of beef heart and men hawking beer and fireworks. When we reached a stage blocking the street, we crawled under it, careful not to disconnect any cables. Night was falling, and the sky darkened to a brooding shade of gray. A storm lit up the vast earthen bowl that the city sits in, clouds rolling toward us.

When the raindrops started to pelt our shoulders, we hailed a collective van headed down into the center, and piled in with some of the revelers. One couple looked so inebriated that when we reached their stop, the driver’s assistant went out in the rain to help them to their door. None of the other passengers said a word. No jokes or criticisms, no complaints about the seven or eight minutes spent waiting. Everyone seemed to understand that tolerance was just one piece of the larger ritual of community, and that being part of such rituals, large and small, was the only way to ever really inhabit La Paz.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1507_Inca_Contrib_03.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SQJ_1507_Inca_Contrib_03.jpeg)