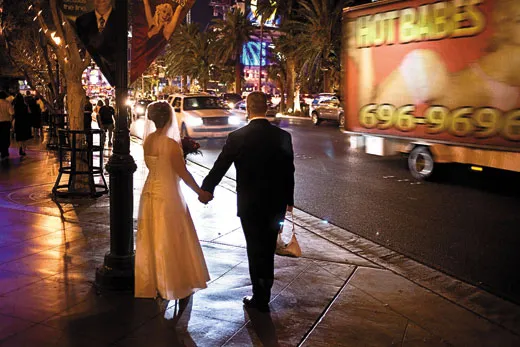

Las Vegas: An American Paradox

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist J.R. Moehringer rolls the dice on life in Sin City

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/My-Town-Las-Vegas-JR-Moehringer-631.jpg)

The last box is packed and taped shut, the moving truck will be here first thing in the morning. My footsteps echo loudly through the empty rooms.

It’s 7 p.m. I’m supposed to meet friends for dinner on the Strip—one last meal before leaving Las Vegas. I’d love to cancel, but the reservation is in less than an hour.

I fall into a chair and stare at the wall. It’s quiet. In two years I’ve never heard it this quiet. I wonder if something is wrong with Caligula.

I think back over the past two years, or try to. I can’t recall specifics. Places, dates, it’s all a blur. For instance, what was the name of that crazy club where we went that time? The Peppermint Hippo? The Wintergreen Dodo?

The Spearmint Rhino. Yes, that was it. Eighteen thousand square feet of semi-nude women. My friend G., visiting from the Midwest, wandered around like a Make-a-Wish kid at Disneyland. He came back to our table and reported, saucer-eyed, that he’d seen Beckham and Posh in a dark corner. We laughed at him. Poor G. He doesn’t get out much. What would Beckham and Posh be doing in some crazy Vegas club? Minutes later, on my way to the men’s room, I ran straight into Beckham and Posh.

I came to Vegas to work on a book. No one comes to Vegas to work on a book, but I was helping tennis great Andre Agassi write his memoir, and Agassi lives in Vegas. It seemed logical that I live here until the book was done.

I knew, going in, that I’d feel out of place. The glitz, the kitsch, the acid-trip architecture—Vegas isn’t me. I’m more a Vermont guy. (I’ve never actually lived in Vermont, but that doesn’t keep me from thinking of myself as a Vermont guy.) Writing a book, however, greatly increased my sense of alienation. Vegas doesn’t want you writing any more than it wants you reading. You can sit by the topless pool at the Wynn all day long, all year long, and you won’t see anyone crack open anything more challenging than a cold beer.

And it’s not just books. Vegas discourages everything prized by book people, like silence and reason and linear thinking. Vegas is about noise, impulse, chaos. You like books? Go back to Boston.

The first time this hit me, I was driving along U.S. 95. I saw a billboard for the Library. I perked up. A library? In Vegas? Then I saw that the Library is yet another strip club; the dancers dress like wanton priestesses of the Dewey Decimal System. The librarian busting out of the billboard asked: Will you be my bookworm?

She almost sat in my spinach salad. I was eating in an overpriced steakhouse west of the Strip when she appeared from nowhere, resting half her derrière on my table. (The steakhouse was crowded.) She wore a miniskirt, fishnet stockings, opera gloves to her elbows. Her hair was brown, curly, jungle thick, and yet it couldn’t conceal her two red horns.

She said a mega-rich couple had hired her for the night. (Beckham and Posh?) They were hitting all the hot spots, and at each spot they wanted her to appear as one of the Seven Deadly Sins. Currently the couple was cloistered in a private back room, “doing something,” and she was keeping out of sight, waiting for her cue.

“What sin are you right now?”

“Sloth.”

I’d have bet the farm on Lust. I wanted to ask if she was free after the traveling sinfest, but the couple was waving, calling her name. They were ready for some Sloth.

The Agassi book almost didn’t happen, thanks to my neighbor, Caligula, and his weekly bacchanalias. The skull-thumping music from his Coliseum-size backyard, the erotic shrieks from his pool and Jacuzzi, made writing all but impossible. Caligula’s guests represented a perfect cross section of Vegas: slackers, strippers, jokers, yokels, models and moguls, they arrived every Thursday night in all manner of vehicles—tricked-out Hummers, beat-up Hyundais—and partied until the shank of Monday afternoon. I learned to wear earplugs. They sell them everywhere in Vegas, even grocery stores.

It always comes as a shock to the newcomer. Of the 130,000 slot machines in Vegas, many are located in grocery stores. Nothing says Vegas like swinging by Safeway at midnight for a quart of milk and seeing three grandmas feed their Social Security checks into the slots as if they were reverse ATMs. The first time this happened to me, I was reminded of my favorite “fact” about Vegas, which is wholly apocryphal: a city law prohibits the pawning of false teeth.

Just after i moved in, Caligula rang my bell. He invited me over for an afternoon “cookout.” I didn’t yet know he was Caligula. Wanting to be neighborly, I went.

I met several statuesque young women in his backyard, in his kitchen. I thought it strange that they were so outgoing. I thought it odd that they were named after cities—Paris, Dallas, Rio. But I didn’t dwell on it. Then I wandered into a room where the floor was covered with mattresses. An ultraviolet light made everyone look super tanned or vaguely satanic. Suddenly I got it. I told Caligula that I just remembered somewhere I needed to be. I shook my head at his offer of a grilled hot dog, thanked him for a lovely time and sprinted home to my books and earplugs.

As a kid I was a gypsy, as a young man I was a journalist, so I’ve lived everywhere. I’ve unpacked my bags in New York, New Haven, Boston, Atlanta, Denver, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Seattle, Tucson. Each of my adopted cities has reminded me of some previous city—except Vegas, because Vegas isn’t a real city. It’s a Sodom and Gomorrah theme park surrounded by hideous exurban sprawl and wasteland so barren it makes the moon look like an English rose garden.

Also, every other city has a raison d’être, an answer to that basic question: Why did settlers settle here? Either it’s close to a river, a crossroads or some other natural resource, or else it’s the site of some important battle or historic event. Something.

The reason for Vegas is as follows. A bunch of white men—Mormons, miners, railroad barons, mobsters—were standing around in the middle of the desert, swatting flies and asking each other: How can we get people to come here? When they actually managed to do it, when they lured people to Vegas, their problem then became: How can we get people to stay? A far greater challenge, because transience is in the DNA of Vegas. Transient pleasures, transient money, thus transient people.

More than 36 million people go through Vegas each year. Before a big heavyweight fight or convention, they fill just about every one of the city’s 150,000 hotel rooms—more rooms than any other city in the United States. At checkout time, Vegas can shed the equivalent of nearly 20 percent of its population.

Though people enjoy coming to Vegas, what they really love is leaving. Every other passenger waiting to board a flight out of Vegas wears that same telltale look of fatigue, remorse, heatstroke and get-me-out-of-here-ness. I spent two months reading Dante in college, but I didn’t really understand Purgatory until I spent five minutes at McCarran International Airport.

When I first opened a checking account in Vegas, my personal banker’s name was Paradise. I wasn’t sure I wanted to entrust all the money I had in this world to a woman named Paradise. In Vegas, she assured me, the name is not that unusual.

She spoke the truth. I met another Paradise. I also met a girl named Fabulous and a girl named Rainbow. She asked me to call her Rain for short.

One Friday afternoon, withdrawing cash for the weekend, I asked the bank teller if I could have it in fifties.

“Really?” she said. “Fifties are bad luck.”

“They are?”

“Ulysses Grant is on the fifty. Grant went bankrupt. You do not want to walk around Las Vegas with a picture in your pocket of a man who went bankrupt.”

Irrefutable. I asked her to give me hundreds.

As she counted out the money, I looked down at sweet, smiling Ben Franklin. I recalled that he had a weakness for fallen women. I recalled that he said, “A fool and his money are soon parted.” I recalled that he discovered electricity—so Vegas could one day look like a phosphorescent candy cane. Clearly, I thought, the C-note is the proper currency for Vegas.

Hours later I lost every one of those C-notes at a roulette table. I lost them faster than you can say Ben Franklin.

Vegas is America. No matter what you read about Vegas, no matter where you read it, this assertion invariably pops up, as sure as a face card in the hole when the dealer’s showing an ace. Vegas is unlike any other American city, and yet Vegas is America? Paradoxical, yes, but true. And it’s never been more true than during these past few years. Vegas typified the American boom—best suite at the Palms: $40,000 a night—and Vegas now epitomizes the bust. If the boom was largely caused by the housing bubble, Vegas was bubble-icious. It should be no surprise, therefore, that the Vegas area leads the United States in foreclosures—five times the national rate—and ranks among the worst cities for unemployment. More than 14 percent of Las Vegans are without work, compared with the national rate of 9.5 percent.

The proof that Vegas and America are two sides of the same chip is the simple fact that America’s economy functions like a casino. Who could dispute that a Vegas mind-set drives Wall Streeters? That AIG, Lehman and others put the nation’s rent money on red and let the wheel spin? Credit default swaps? Derivatives? The backroom boys in Vegas must be kicking themselves that they didn’t think of those things first.

The house always wins. Especially if you never leave the house. Vegas has been home to some of the most notorious hermits in American history. Howard Hughes, Michael Jackson—something about Vegas attracts the agoraphobic personality. Or creates it.

As my time in Vegas wound down, I often found myself bolting the door and pulling down the window shades. My self-imposed seclusion was motivated partly by Caligula, partly by my book. Facing a tight deadline, I had no time for Vegas. Consequently I went weeks in which my only window on Vegas was the TV. Years from now my clearest memories of Sin City might be the ceaseless stream of commercials for payday loans, personal injury lawyers, bail bondsmen, chat lines and strip clubs. (My favorite was for a club called the Badda Bing, with a female announcer intoning: “I’ll take care of that thing. At the Badda Bing.”) From TV, I concluded that a third of Vegas is in debt, a third in jail and a third in the market for anonymous hookups.

Many of those personal injury lawyers were jumping for joy in 2008, when a local gastroenterology clinic stood accused of gross malpractice. To save money, the clinic allegedly used unsafe injection practices and inadequately cleaned equipment. Thousands of patients who went there for colonoscopies and other invasive procedures were urged to get tested immediately for hepatitis and HIV. A wave of lawsuits is pending.

With growing horror, I watched this medical scandal unfold. To my mind it symbolized the Kafkaesque quality of 21st-century Vegas, the negligence and corruption, the widespread bad luck.

Some nights on the local news a segment about the clinic would be followed by a piece about O.J. Simpson’s brazen armed robbery at a local casino hotel, then one on Gov. Jim Gibbons’ denial of a sexual assault allegation, or a story about Nevada’s junior senator, John Ensign, cheating on his wife, though he had once declared on the floor of the United States Senate that marriage is “the cornerstone on which our society was founded.” Shutting off the TV, I’d walk to the window, listen to a nude game of Marco Polo raging around Caligula’s pool, and think: I have a front-row seat at the apocalypse.

I shave, get dressed, drive down to the Strip. My friends, a man and a woman, a longtime couple, love Las Vegas. They can’t imagine living anywhere else. Over tuna sashimi, Caprese salad, ravioli stuffed with crabmeat, they ask what I’ll miss most about the town.

The food, I say.

They nod.

The energy.

Of course, of course.

What I don’t say is this: I’ll miss the whole seamy, seedy, icky, apocalyptic tawdriness of it all. While I was busy hating Vegas, and hiding from Vegas, a funny thing happened. I grew to love Vegas. If you tell stories for a living or collect them for fun, you can’t help but feel a certain thrill at being in a place where the supply of stories—uniquely American stories—is endless.

That doesn’t mean I’m staying. Vegas is like the old definition of writing: though I don’t enjoy writing, I love having written. Though I didn’t enjoy Vegas, I love having lived there.

I deliver an abbreviated summary of my time in Vegas to my two friends. I hit the highlights—Caligula, Sloth, the clinic that rolled the dice with people’s colons.

“We went there,” the man says.

“We were patients,” the woman says.

“Oh no,” I say. “How awful.”

The question hovers.

“Negative,” the man says.

“We’re both fine,” the woman says.

I sigh. We all smile, with relief, with gratitude.

You have to be grateful in Vegas. It’s the great lesson of the city, the thing I’m taking with me as a souvenir. If you can live in Vegas, or visit Vegas, and leave in one piece, still loving it and somehow laughing about it, you should spend at least part of your last night in town doing something that will serve you well no matter where you go next: thank your lucky stars.

J. R. Moehringer wrote the best-selling memoir The Tender Bar.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.