For nearly 50 years, a 1,500-pound bell known as “El Reloj” kept the neighborhood of Ybor City, northeast of downtown Tampa, on schedule. It was the early 1900s in the immigrant enclave, long before cell phones, and its various chimes would notify workers when it was time to leave for the factory, when families were late for church and when children needed to stop the baseball games in order to be home for dinner. The famous clock tower was not part of a church or a city building, as you might suspect. It was on top of a cigar factory.

In the early 1900s, Ybor City was the cigar capital of the world. The port city’s subtropical weather and close proximity to Cuba made it an ideal hub for cigar manufacturing. At its height, it is estimated that 10,000 cigar rollers worked in 200 cigar factories producing up to a half-billion hand rolled cigars a year. Each cigar factory was designed in the same manner: a three-story building, 50 feet across and situated east to west to minimize damage from hurricanes and maximize sun exposure and circulation from breezes. In 1910, when the Regensburg Cigar Factory, affectionately nicknamed El Reloj because of its clock tower, opened it was the world’s largest cigar factory in terms of square feet, designed to accommodate 1,000 cigar rollers who could roll more than 250,000 cigars a day or 60 million per year.

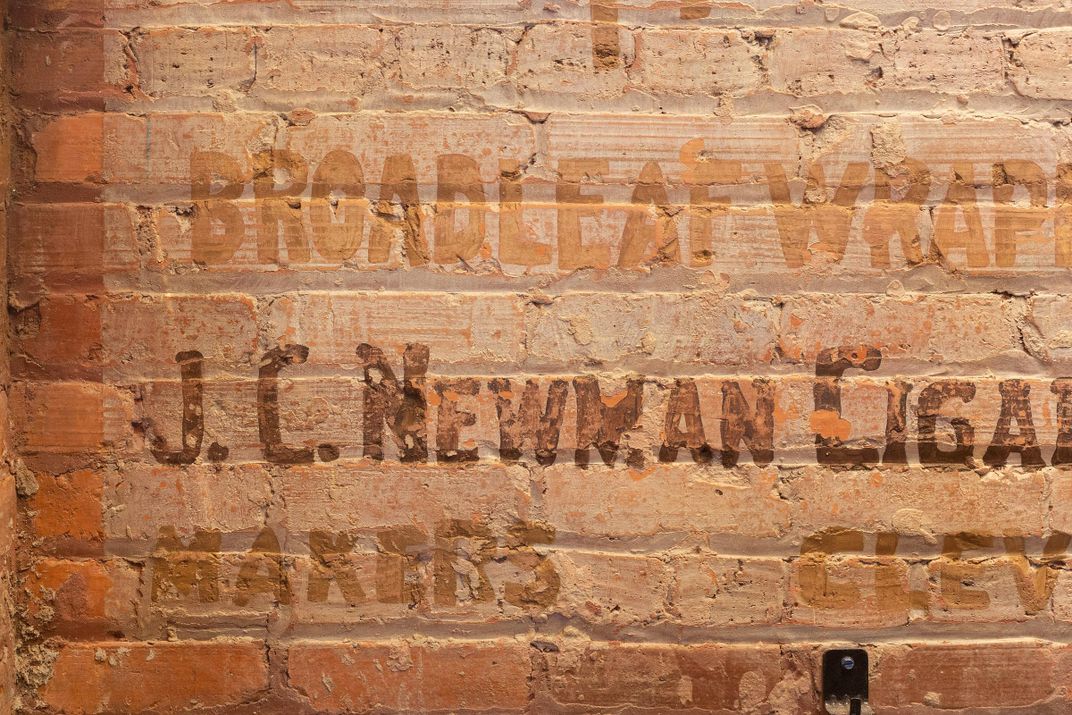

To honor the city’s cigar-making legacy, in 2020, owners converted 1,750 square feet of the factory, now the J.C. Newman Cigar Company, into a history museum that includes artifacts dating back to 1895. The company began tours through the working factory, and the chimes from the restored clock tower ring out again over Ybor City.

The city itself was named after Spanish immigrant Vincent Martinez Ybor, who moved his cigar factory from Cuba to Florida in 1885. By 1890, Ybor City’s population was around 6,000. Though many of the residents were Hispanic, immigrating from Spain or Spanish Cuba, there were also Italian, German, Romanian Jewish and Chinese immigrants in Ybor City. The incoming immigrants began transforming the swampy Tampa outpost into a trilingual, intercultural neighborhood. The smell of freshly baked Cuban bread filled the streets in the morning; Italian, Jewish and Cuban social clubs popped up along the main avenue; and the sounds of Flamenco music drifted out of bars at night.

“Cigars built this city,” says Ybor City historic district ambassador Bob Alorda. “Parents would teach young children to roll cigars at kitchen tables because they wanted their kids to know the neighborhood trade.”

Pockets of Ybor City’s history remain. Roosters still roam the streets cackling at dawn. La Segunda Bakery still bakes homemade Cuban bread as they did in 1915. A red, white and green flag still waves outside the Italian club, and patrons still stop by the Columbia Restaurant for a cup of coffee as they did in 1905. But the neighborhood’s numerous cigar factories have all been torn down or converted into other businesses, except for one—El Reloj.

Popularity of cigarettes over cigars, the Great Depression and the rise of factory machines began the slow decline of the cigar industry in the 1930s. The Cuban embargo of 1962 dealt a final blow to the cigar industry shutting most of Ybor City’s factories. Tampa’s urban renewal project in 1965 ushered in the destruction of blocks of factories to make way for a new highway and developments.

In 1953, the J.C. Newman Cigar Company bought the Regensburg Cigar Factory and moved its operation from Cleveland, Ohio to Tampa. Today it is not only the last remaining cigar manufacturing factory in Tampa, but it is the only surviving traditional cigar company from the early 1900s in the entire United States. Just over 150 employees handcraft 12 million cigars a year from the historic factory.

“Today, everyone whose family has lived in Tampa for a few generations had relatives who rolled cigars, made cigar boxes, prepared meals for cigar workers or were connected to the cigar industry in some other way,” says Drew Newman, fourth-generation owner and general counsel. “Cigars are an important part of the cultural fabric and history of Tampa.”

Realizing they had the last remaining cigar factory in Tampa, the Newman family believed it was their responsibility to keep the city’s historic cigar-making tradition alive and share it with future generations.

Structural improvements to the clock tower, the conversion of a 2,000-square-foot storage area into a traditional hand-rolling station, and the restoration of tile, paneling and flooring to its original environment were all part of the recent multi-million dollar renovation.

The museum begins on the factory’s first floor where historic relics from the early days of the cigar industry like a mason jar humidifier are on display. From there, a docent-led tour guides visitors through the three-story working factory.

The 75-minute tour starts in the basement as visitors are led through the aging room, a climate-controlled space maintained at 64 percent humidity where piles of Cameroon leaf and Pennsylvania broadleaf tobacco age for three years. The last pre-embargo bale of Cuban tobacco in the United States from the 1958 harvest sits untouched on a cart in the corner of the basement.

The tour continues through the second-story factory floor where the sound of creaky wooden floors gives way to the constant buzz of 90-year-old machines at work. Employees sit at pea green machines stretching tobacco leaves over metal molds to cut out perfectly-shaped cigar wrappers. The machines are so old that Newman employs mechanics specifically to keep their 10,000 moving parts in top shape. If parts are needed, the mechanics recreate them as the manufacturers of the pieces are long gone.

While the majority of the cigars are made by machine, three hand rollers work on the factory’s top floor rolling the company’s premium cigars. The floor has a space where a lector, in the early 1900s, would read a variety of texts from classic literature to the daily newspaper to keep workers entertained while working. Texts were read in Spanish, English and Italian, which is why many of the workers were trilingual despite receiving little formal education. It is also the reason many cigar brands were named after characters in classic literature like Romeo y Julieta, Montecristo and Sancho Panza.

“The United States has a rich tradition of cigar making that dates back to the first crop of tobacco that was grown in the Virginia colony in 1612,” says Newman. “My goal is to continue our family legacy of handcrafting premium cigars in the United States and to keep the tradition of American cigar making alive. We have an authentic American story, and I want to tell it.”

While the cigar making process has not changed much since its inception, the Newman family wants to incorporate Cuban tobacco back into their cigars.

J.C. Newman recently filed a petition with the U.S. Department of State requesting the authorization to import tobacco grown from independent Cuban farmers, explains Newman. If granted, J.C. Newman will be the first importer of Cuban tobacco in 60 years.

“We received positive news from both the U.S. and Cuban governments that they were considering our request to import raw tobacco leaves from independent Cuban farms so that we can hand roll them into cigars at El Reloj, just like my great-grandfather and grandfather used to do prior to the embargo,” Newman says.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/a9/cba9c1a9-8659-458c-86b3-7c83b365345b/jc_newman_cigar_company_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/34/d6/34d69cfb-6c1d-4f3e-8f73-8863ca59a00f/jc_newman_cigar_company_banner.jpg)