A Photographer’s Quest to Document the Last of the Rainforest Caribou

In a new book, photographer David Moskowitz turns his lens on the story of a rapidly declining species and habitat

Four years ago, David Moskowitz trekked into the world’s last inland temperate rainforest, stretching a short range from northeastern Washington and northern Idaho to southeast British Columbia in Canada. He hoped to get a glimpse and photograph the elusive mountain caribou, an animal known to live in this unique ecosystem. What he found was catastrophe. Moskowitz discovered that both the mountain caribou and their home are deeply endangered, and are becoming more so every day. Very few herds still exist and are limited to the Selkirk Mountains region, but the most endangered, the Selkirk herd, may already be extinct.

“I was driving up the road, and I saw their habitat coming back down the road on logging trucks,” Moskowitz told Smithsonian.com, speaking of the part of the forest that hasn't yet been protected. “I couldn’t believe we are actually, today, in the 21st century, clear-cut logging old-growth rainforest. It was this epiphany for me, just how utterly unbelievable the landscape these animals occupy is and what we're doing to that landscape.”

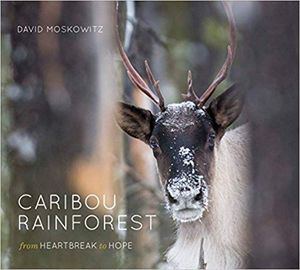

After some digging, Moskowitz discovered the caribou’s plight is mainly driven by our hunger for paper pulp. The temperate rainforest in which they live—an ecosystem that is rare and seeing its own life fade away—is being torn down, tree by tree, to become paper. The effects of this on the forest and the caribou are dire. And although the paper industry is the largest issue, the caribou are facing an onslaught of other issues: new predators, disruptive recreational travelers, mineral extraction and climate change. In an effort to bring visibility to the issue and to help create change, Moskowitz began creating a book, Caribou Rainforest: From Heartbreak to Hope, to share the plight of the caribou and their habitat.

The mountain caribou are unique among other species of woodland caribou, of which they're considered a subspecies. In the winter, they migrate to high alpine peaks, essentially using large snowfall as an elevator to reach the untouched tree lichen that feeds them through the season. No other types of caribou live in the high mountains during the wintertime. Currently, the mountain caribou only live in this inland rainforest habitat. At one time, though, before logging and hunting and other habitat dangers became a concern, they also lived in northwestern Montana and central Idaho. Only about 2,000 mountain caribou remain, mostly in Canada. The small population that crossed into the U.S. has dwindled to only three caribou. The Endangered Species Act lists all species of woodland caribou as endangered, and the population is red-listed in Canada. A few programs are in place to aid the caribou, like the Mountain Caribou Project, but it's a hard sell—in the U.S. in particular, snowmobile groups are lobbying to decrease the listed threat level of the mountain caribou in order to make it easier for snowmobiles to go through the protected land.

Smithsonian.com spoke to the photographer and author about his exploration into the world of the endangered mountain caribou.

What makes the forest so unique?

The caribou rainforest, formally known as the Inland Temperate Rainforest located in British Columbia's Interior Wetbelt and a small part of the Pacific Northwest, is the only remaining intact inland temperate rainforest on planet Earth. A temperate rainforest refers to a rainforest that is in the temperate regions of the world as opposed to the tropics. And then inland refers to it being hundreds of miles from the coast. There are a few spots on the planet where they have existed in the past, but here in the Pacific Northwest is the only place where humans haven't destroyed that forest yet. So we still have vast tracts of original primeval, old-growth, inland temperate rainforest here and nowhere else on the planet. It's really this exceptionally unique ecosystem.

What issues are the caribou facing?

The original challenge for the caribou had to do with things like market hunting. When miners and colonists came into the region, the caribou were hunted for food at unsustainable rates. That carried on, in some places, into the 90s. But even though market hunting has completely stopped and the indigenous people have stopped hunting them of their own volition, caribou populations have continued to decline. And that is 100 percent because we destroyed their refuge habitat. Mountain caribou have this amazing lifestyle where they are dependent on these huge tracts of old-growth forest. The reason they can survive there is because nothing else will live there. There's no deer, elk or moose in these vast tracts of old-growth forest because all those animals have a different habitat. There are almost no predators. The caribou basically had this whole rainforest kingdom to themselves. As we've gone in and logged that habitat, we've invited moose and deer and, in some cases, elk to come into those areas. Caribou didn't evolve to have a high level of predation pressure. These other animals can tolerate it, but caribou can't. So the caribou population has plummeted.

How would the forest itself and any other wildlife living there be affected if the caribou go extinct?

The caribou has been used as an umbrella species to protect these forests. So by protecting the habitat for caribou, the idea was that we're preserving a representation of the ecosystem itself. British Columbia has said, point-blank, that habitat is protected for caribou. If the caribou disappear and there's no chance of them returning, then the habitat protections will be removed. And similarly in the United States, there are critical habitat designations for mountain caribou. If those habitat protections were removed, the forest itself would be at risk for removal, which would impact everything in that ecosystem. It’s one of the other reasons I think this story is so important. It's a parable for this moment in time in conservation. The Endangered Species Act was this amazing progressive idea in the 1970s. But now our understanding of how ecosystems work and the threats that ecosystems face today are very different than what things were in the 1970s. Yet we have conservation legislation mandating things like species-level protection. We really need to be thinking on an ecosystem level. People have tried to use species-level protection to get at preserving an entire ecosystem, and it's just not working.

Did you have any particular struggles that you faced while working on the book?

The animals are really hard to find. It took years of fieldwork to actually find and photograph some of them. The camera trapping efforts involved lots of time in the field looking at tracks and signs, and learning how to predict where these animals would return to. We also consulted local experts whenever possible to point us in the right direction. I also did a number of multi-day backcountry expeditions by foot, ski, and canoe in every season of the year. Additionally, I joined researchers and managers on a few occasions that were going to be carrying research activities I could tag along for. And another challenge, honestly, was just the emotional experience of daily trekking. Driving sixty miles on logging roads of clear-cut rainforest just to get to the end of the road where they haven't logged yet, and then trying to photograph the rainforest and the animals in it. Just recognizing how raw and how real it is. This is an environmental tragedy unfolding underneath our gaze. Having to face that every day was very challenging, but it was also a big driver of why we needed to get this story out there today, while there's still a chance for something different in the future.

Was there anything that particularly surprised you while you were working on the book?

The history of mountain caribou and how the species was perfectly tailored to this globally unique ecosystem was fascinating to unpack. You can find caribou all over the northern hemisphere, but nowhere else in the world do they migrate twice every year and, rather than latitudinally across big landscapes, they go up and down the mountains to access different things they need. Some places in the high mountains get sixty feet of snow in the winter. The caribou go up to the tree line to where it snows the most to spend the winter, then they use the snow basically as an elevator to take them up to their food. They're eating arboreal lichens. As the snow falls, they get access to higher and higher levels of the trees, and so they get access to more and more food. And nothing else will live at the tops of the mountains in the wintertime, so they don't have to worry about predators at all. The problem is that now we have a heli-ski industry dropping humans into that beautiful caribou habitat, and that causes the caribou to have to travel more to avoid humans. And that's negative on their energy budget. So the struggle to figure out how we, as humans, can care for an ecosystem and species within it while still getting our basic needs and recreational enjoyment desires met was another fascinating part of the story to unpack.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/JenniferBillock.png)