McCarthy, Alaska, is a shell of a place. Located in the Valdez-Cordova census area, about 300 miles east of Anchorage, it is a ghost town, with a meager population of 28. Wooden structures, now worn into dilapidated ruins by time and the elements, are backdropped by looming, snow-capped mountain peaks. They remain as testaments to the town’s frontier glory days a century ago.

When Dublin-born photographer Paul Scannell journeyed to Alaska from London in 2016, he didn’t expect to end up in McCarthy and nearby Kennecott. He first traced Christopher McCandless’ footsteps to the abandoned bus made famous by the movie Into the Wild, but ended up prolonging his stay in Alaska. Both settlements were erected in the early 1900s, when the copper and gold mining industries brought frontiersmen and their families up north to seek their fortunes. In their glory days, about 1,000 people resided in the area, and yet the towns are nearly devoid of human life today. Wisps of former residents persist in a scrap of a poster of a woman still staring from the wall, a rusted jam jar left on a table, a discarded boot. After copper prices fell during the Great Depression, the mines depleted and ceased operation in 1938.

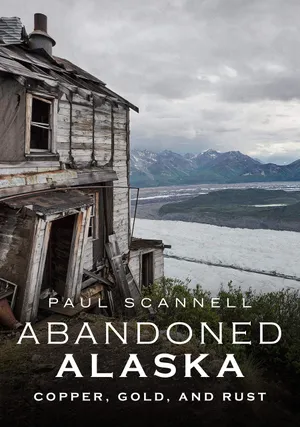

Abandoned Alaska: Copper, Gold, and Rust

Photographer Paul Scannell has spent years hiking to the region's precariously perched mountain-top copper mines and remote gold mining sites with the aim of capturing America's slowly disappearing frontier history.

Scannell, a real estate photographer, merged his eye for photographing residential structures with his passion for shooting natural scenery to capture McCarthy, Kennecott and surrounding mines: Jumbo, Bonanza, Erie, Bremner and Chititu. Since 2016, the haunting beauty of these mines and the towns built around them has kept him returning to them again and again. Scannell recently spoke with Smithsonian about his northern expeditions, the bygone era in American history he captures, and his new book, Abandoned Alaska.

What was it about Alaska in particular that attracted you to that area?

It was the landscape. I love moody Northern places, rainy, misty, foggy places. I’m from Dublin, so I was used to that sort of landscape. I just wanted to bring my camera and be in the wild. It was kind of like an early midlife crisis.

I had decided to go to Alaska, and then the magic bus [from Into the Wild] seemed like a cool place to go. Once I got to the bus, I happened upon this community, McCarthy, completely by accident, really. We were traveling around, me and my friends who had gone to the bus. We had a few different options: we could go up north to the sign for the Arctic Circle, but that would have been like a 10-hour drive to just take a photograph of a sign. Or we could go to this quirky town called McCarthy. I have always been fascinated with abandoned buildings. We were only supposed to stay a night, and then as we were reversing out of the car park, I knew I wasn't leaving. I had a total drama queen moment because my flight was the next day from Anchorage. I was going to do the quintessential Greyhound bus journey around America, but why would I leave the coolest place I've ever found in search of somewhere cool? So I flipped a coin. It landed on stay, so I stayed. I still have the coin. It's an Icelandic Kroner. I bring it with me.

What were you looking for on your journey in Alaska? Did you find it?

Moody landscapes, the moody scenery, and the sense of being tiny. I suppose the sense of being lost, feeling a little lost in this vast space. At its simplest, I just wanted to be in a forest setting as well, and I wanted to use all my lenses. I think if you can’t take a good photograph in Alaska, you don't deserve a camera. It's such a beautiful place. I found the landscapes. I found glaciers. I found forests. I found those beautiful road shots that go on forever. It was so exciting. Then I found a human element as well; I found history, and I found stories. It was definitely the best place I've ever been.

How did you learn about these abandoned mining towns, and logistically, what does it take to get to them?

They’re all based around Kennecott and McCarthy, which is in the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. They’re all accessible. If I got there, anybody can get there. I’m a little bit hapless; I’m not this rugged, capable hiker. So planning out each hike, for me, was about finding out how dangerous it was and getting to know who had been there before and keeping my ear out for people that were headed there. There are companies that do guided hikes. I never did a guided hike; I always just went with friends. For example, with Chititu, you would be picked up in McCarthy, flown there and just left in the wild, and you have to hike the rest of the way yourself. There is always that uncertainty. If the weather gets really bad the pilot just can’t come and get you, so you have to pack enough food to last for at least a few days more than you’re going to be going.

What surprised you about the history of these boomtowns?

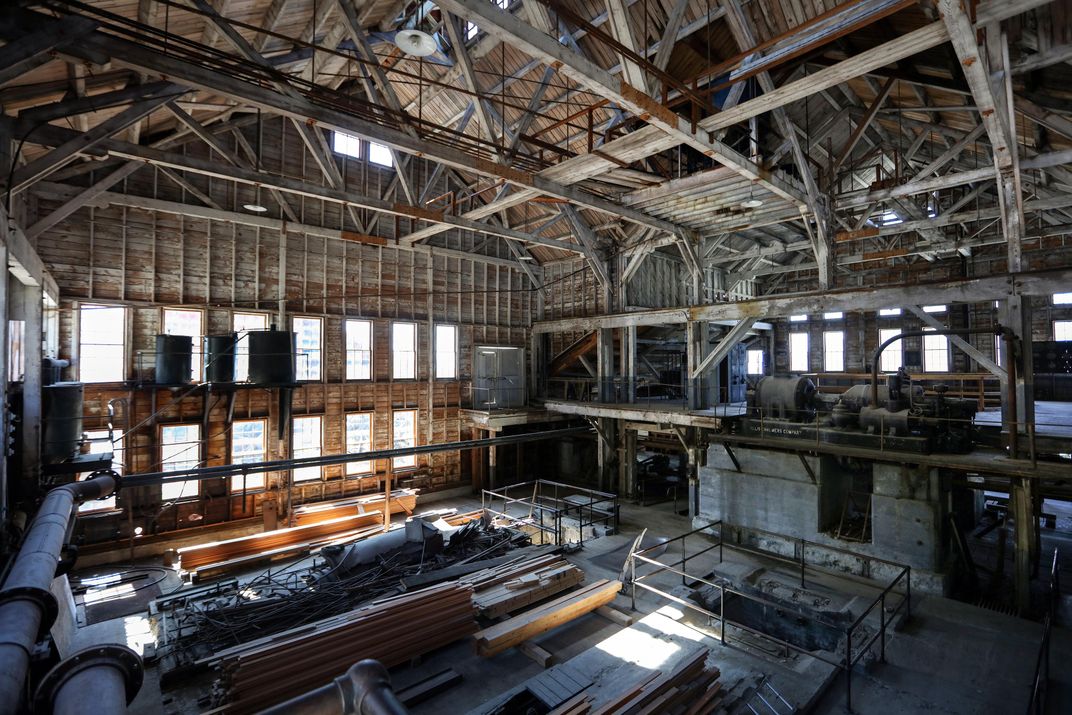

The history is so overwhelming, there's so much to know. Kennecott was dry, which meant that it was just a place of work. Then McCarthy grew up around the train turntable like five miles down the road, and that was the center of booze, liquor, vice, the honky tonk pianos, the working girls, all those things attached to a wild western town, a frontier town. After 1938, both were effectively ghost towns. There was a huge fire in the 1940s as well, which destroyed a lot of McCarthy.

What is it about dilapidated spaces that makes you want to document them?

It's definitely the human aspect. I can walk into a modern building and get a bit of an on-edge feeling, or I can walk into what is traditionally a creepy old building and actually feel safe and connected. I suppose that that is the human aspect of it. It was an extraordinary immersion to have these people’s little things lying around, like a lady's boot from a hundred years ago just sitting there, cups that they would have drank from. These mines, many of them were given one day's notice to vacate, so the people that have been working there for 25 or 30 years were on the last train, effectively. These people just had to leave everything. They had to carry what they could on their backs, get on the last train or they were stuck there. It was amazing. It's like being on the Mary Celeste.

Do ghost towns strike you as a part of nature or a part of human society, or somewhere in between?

It’s a weird mix. It’s like nature is trying to take these places back. Alaska’s tough. They say Alaska’s always trying to kill you. It’s like the landscape is insisting that it gets its land back. With Erie, the mountain has actually moved to the point where it is pushing [the mine] off the mountain. Where you enter, there’s a point where the mountain has started breaking into the mess hall. There’s this battle going on with this epic, endless landscape that is vicious but beautiful. [The landscape] is saying a tiny bit every year, ‘I’m taking you back. You should have never been here. You’re the anomaly.’ So that’s what it felt like, that’s the drama. Nature’s going to win.

What were you trying to capture in your photographs?

I was trained in interiors photography, but with a completely different setting—overpriced London real estate. The places I was always drawn to far more were the ‘doer-uppers,’ something that somebody’s lived in for many years and has just fallen into disrepair, for that sense of human history, things still hanging in an old wardrobe, old photographs lying around. So with these places I wanted to set the scene, capture the mood. I wanted to let somebody know what it feels like to be there. That would be from a wide-angle perspective shooting the room, but then also honing in on details and capturing them in their natural state. I had a rule, I never wanted to stage anything. None of those photographs were staged. It was never ‘let’s make this look creepy.’ Everything was photographed as I found it.

Do you have a favorite of all the photos you took, or a favorite memory from your time in Alaska?

The Jumbo [mine] bunkhouse used to be up on stilts, and then on one end it collapsed, so you enter in and you’re walking up. You feel like you’re fighting your way through a sinking ship. It feels like you’re on the Titanic. As you’re pulling yourself up from each doorframe, you’re looking in and there are bunk rooms on either side and all the old beds, bed frames, bed sheets and socks, they’re all just lying around. ‘Bunk Interior’ really sums up for me what it felt like to be in that building because everything’s gone sideways. You feel like if you cough, you’re dead, because the whole thing could fall over.

Also ‘Poster Girl.’ It brings you back to that era. The poster would have been 1930s; that’s why I always think Hollywood starlet. It says so much that there’s only a tiny scrap of her face left, and when it’s gone people will never even know it was there in the first place. There’s something really spooky about that.

What made you want to share these photos with the public?

There is a natural fascination with abandoned places. I think people are naturally drawn to these places, and I felt so lucky to be able to be the one to show them. There’s a degree of pride in that, that I really did have to push myself and I was terrified getting to some of those places. I’d love to meet people who said, ‘I went there because I saw your photograph.’ That would be the greatest honor.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/d4/35d48952-dc33-4f1d-aca5-bdede33a1267/abandoned_alaska_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/fa/02fa56c1-b64b-42ff-9d84-14a63094fb37/abandoned_alaska_header.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tara.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/tara.png)