Life Aquatic

The sailing world docks in Annapolis

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/annapolis_388.jpg)

A lone green buoy sways in the Severn River, a couple hundred feet off the Annapolis harbor. Roughly 150 sailboats float near it, ready, on their marks. Then, around 6 p.m., a flag raises, a gun shot sounds, and go! With the Chesapeake Bay Bridge providing the backdrop, the boats take off. They sail two miles out into the Bay then race back into the harbor, crisscrossing to avoid docked boats. The town watches as the boats pull to a finish, around 7:30, just past the drawbridge in front of one of the yacht clubs.

This is not a special event, just a regular Wednesday evening in "America's Sailing Capital."

Annapolis and surrounding Anne Arundel County has enjoyed a long association with the water. The area boasts 534 miles of shoreline on the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries, more than any other county in Maryland. Settlers in the mid-1600s found the shallow harbor—it's only 14-feet deep—and the proximity to the Bay and the Atlantic Ocean an ideal place from which to ship tobacco to London. Because of this convenient location, Maryland's colonial governor Francis Nicholson moved the capital of Maryland in 1694 from St. Mary's City to Anne Arundel Town, an area Nicholson soon renamed Annapolis in honor of Anne, the heir to the British throne.

During the late 1700s, as colonies began shipping more grains than tobacco, boats grew too large to fit in Annapolis's shallow harbor. Baltimore soon emerged as the next big shipping port, leaving Annapolis in search of a new identity.

"In the 1800s and 1900s, the vacuum in the harbor was filled with fishing vessels," says Jeff Holland, director of the Annapolis Maritime Museum. New England fishermen came south to harvest oysters. The shellfish, which eat sediment and algae in the water through an internal filtering system, abounded in the Chesapeake Bay at that time. There were so many oysters, says Holland, that they could filter the entire Bay—all 19 trillion gallons of it—in just 3 days. This made the water clear and pristine. Soon, says Holland, "local watermen picked up on the fact that they had a gold mine." And so did the harbor businesses as they began to cater to the fishermen.

By the mid 1900s, though, over-fishing and pollution led to a decline in the oyster population. "Today, we have a fraction of 1 percent of what we had," says Holland. As the fishing boom waned, the 1938 invention of fiberglass, which revolutionized recreational boating, began to shape the next phase of the Annapolis harbor. People no longer had to pay high prices for hand-made wooden boats; they could buy much cheaper sailboats made from fiberglass molds.

Sailors such as Jerry Wood, who founded the country's oldest and largest sailing school in 1959 in Annapolis and started the first in-water sailing show in 1970 in the area, helped bring attention to the tidewater town. Rick Franke, who started teaching at Wood's Annapolis Sailing School in 1968, now runs the program, which was created to offer adults sailing lessons. "It was a revolutionary idea in those days," says Franke. In 1996, the school allowed children to participate. Now hundreds of kids, some as young as five years old, learn to sail every year. "It's like a floating kindergarten," says Franke of the group they call "Little Sailors." High winds and very few rocks make the Chesapeake Bay an easy sail. The water is "a sailor's dream," says Holland. "It's essentially a big bathtub."

For more veteran sailors, yacht clubs in the area provide some healthy competition. Boat races, or regattas, big and small are scheduled throughout the season, and some of the die-hards even sail during the winter in what the community calls "the frostbite schedule." The regular Wednesday night races, hosted by the Annapolis Yacht Club, started in 1950 and run from May through October. Many locals look on from the harbor, others sail out a bit for a closer look at the action. Last year, the Volvo Ocean Race—an around-the-world competition considered by many to be the ultimate sailing race—stopped in Annapolis for the third time.

Although many sail to Annapolis for the optimal conditions, they stay for the quaint small town and sense of community. The rotunda of the Maryland State House, built in 1789, the oldest state house still in legislative use, is perched atop a small ridge in the center of town. Main Street, a pathway of colonial brick buildings filled with boutiques, ice cream parlors and restaurants serving up such fares as the area's famous crab cakes, slopes down to the city dock. The United States Naval Academy, which makes its home in Annapolis, sits on a rocky shoreline nearby. The school, which was established in 1845 at Fort Severn in Annapolis, left for safer waters in Rhode Island during the Civil War. It returned, though, and rehabilitated the campus, which is now open to the public for a stroll along the water.

The water has also contributed to a whole way of life celebrated by locals. In the last 30 years, groups such as Them Eastport Oyster Boys have created music about the Bay. In nearby Eastport, the Annapolis Maritime Museum honors the work of the watermen and the history of the boat culture. The museum staff includes its director Jeff Holland, who conducts business with his dog at his feet. "I came here on a sailboat and never left," he says. The museum hosts a lecture series and provides outreach programs for local youth. They are currently renovating the old McNasby Oyster Packing House, which once was the place to sell, shuck, pack and ship Chesapeake oysters. By the end of the year, Holland hopes to open the facility to the public.

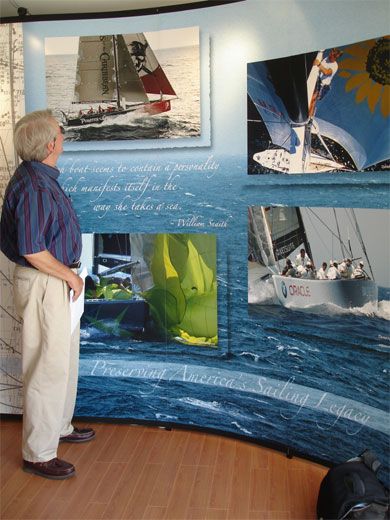

In 2005, some of the biggest names in sailing chose Annapolis as the home of National Sailing Hall of Fame. With a temporary exhibit now at the city dock, a permanent exhibit will open in the near future. And from May 4-6, Annapolis will host the annual Maryland Maritime Heritage Festival, an event filled with music and other entertainment, all focused on the area's connection with the water.

Even though these events and museums draw crowds, the locals don't need an excuse to turn their attention to the water. For people like Jennifer Brest, it happens nearly everyday. On a recent day at the town's harbor, Brest's Woodwind II swayed to the wind's rhythm. She and her colleagues readied the schooner for a private charter in the afternoon. During the season, the Woodwind II sails up to four times a day on cruises open to the public. "People say we are the best part of their vacation every time," says Brest, who enthusiastically showed off pictures of her and her crew with the cast of the movie Wedding Crashers. Part of the film was shot on the Woodwind II.

Brest's passion for sailing is contagious, and she points out that the sailors in town are very social and close-knit. For example, Rick Franke, the head of the Annapolis Sailing School, often helps with the Woodwind II trips. On Thursdays, Brest hosts a local music night on the boat. Who's a frequent performer? Them Eastport Oyster Boys, the band started in part by Jeff Holland of the Annapolis Maritime Museum, along with Kevin Brook. One of their songs sums up the feel of Annapolis nicely: All you need, they sing, is a "good hat, a good dog, and a good boat."

Whitney Dangerfield is a regular contributor to Smithsonian.com.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.