Looting Mali’s History

As demand for its antiquities soars, the West African country is losing its most prized artifacts to illegal sellers and smugglers

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Mali-Dogon-region-figurines-631.jpg)

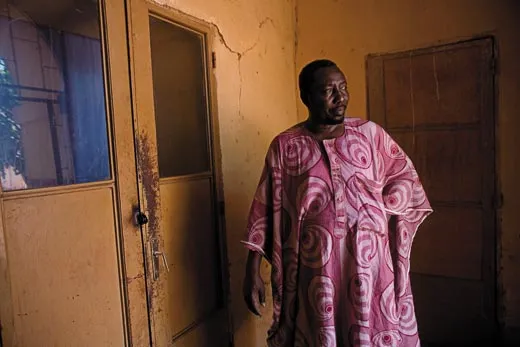

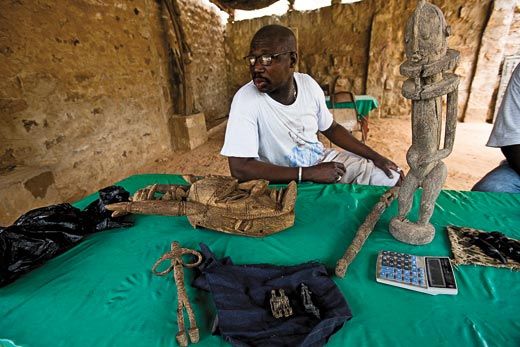

I'm sitting in the courtyard of a mud-walled compound in a village in central Mali, 40 miles east of the Niger River, waiting for a clandestine meeting to begin. Donkeys, sheep, goats, chickens and ducks wander around the courtyard; a dozen women pound millet, chat in singsong voices and cast shy glances in my direction. My host, whom I'll call Ahmadou Oungoyba, is a slim, prosperous-looking man draped in a purple bubu, a traditional Malian gown. He disappears into a storage room, then emerges minutes later carrying several objects wrapped in white cloth. Oungoyba unfolds the first bundle to reveal a Giacometti-like human figure carved out of weathered blond wood. He says the piece, splintered and missing a leg, was found in a cave not far from this village. He gently turns the statuette in his hands. "It's at least 700 years old," he adds.

Oungoyba runs a successful tourist hotel next door to his house; he also does a brisk business selling factory-produced copies of ancient wooden statuettes and other objects to the Western package-tour groups that fill the hotel during the winter high season. But his real money, I've been told, comes from collectors—particularly Europeans—who may pay up to several hundred thousand dollars for antique pieces from villages in the region, in defiance of Malian law. My guide told Oungoyba that I was an American collector interested in purchasing "authentic" Dogon art.

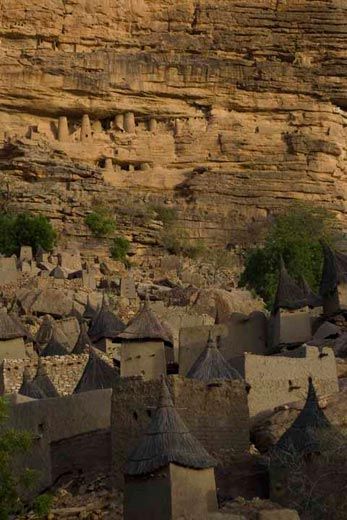

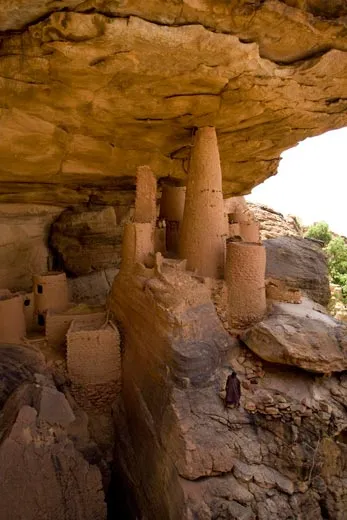

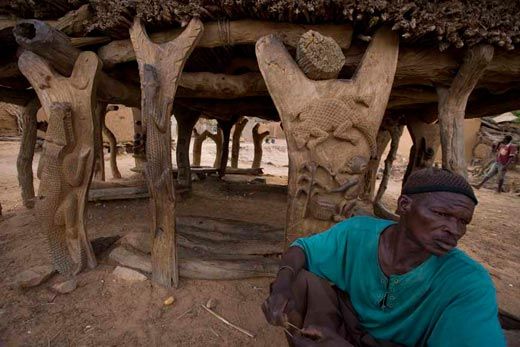

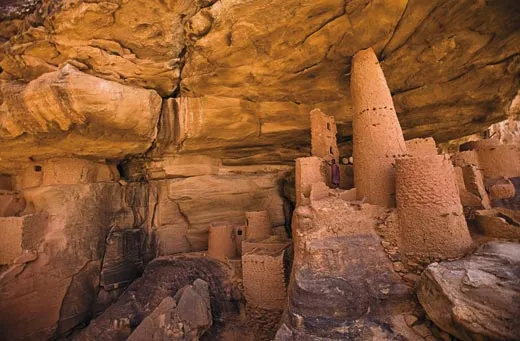

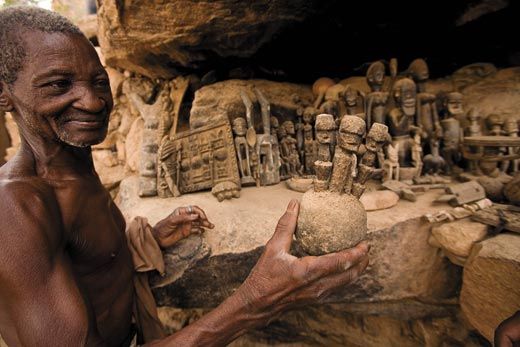

The Dogon, subsistence farmers who hold ancient animist beliefs, are one of central Mali's ethnic groups. In the 15th century, or even earlier, perhaps fleeing a wave of Islamization, they settled along the 100-mile-long Bandiagara Cliffs, which rise just above this village. The Dogon displaced the indigenous Tellem people, who had used caves and cliff dwellings as granaries and burial chambers, a practice the Dogon adopted. They built their villages on the rocky slopes below. Today, the majority of the estimated 500,000 Dogon remain purely animist (the rest are Muslims and Christians), their ancient culture based on a triumvirate of gods. Ritual art—used to connect with the spiritual world through prayer and supplication—can still be found in caves and shrines. Dogon doors and shutters, distinctively carved and embellished with images of crocodiles, bats and sticklike human figures, adorn important village structures.

On the porch of his private compound, Oungoyba, a Dogon, unwraps a few additional objects: a pair of ebony statuettes, male and female, that, he says, date back 80 years, which he offers to sell for $16,000; a slender figurine more than 500 years old, available for $20,000. "Check with any one of my clients," he says. "They'll tell you I sell only the real antiquities."

Two days earlier, in the village of Hombori, I had met an elderly man who told me that a young Dogon from the village had been cursed by the elders and died suddenly after stealing ancient artifacts from a cave and selling them to a dealer. But endemic poverty, the spread of Islam and cash-bearing dealers such as Oungoyba have persuaded many Dogon to part with their relics. Indeed, Oungoyba says he purchased the 700-year-old human figure, which he offers to me for $9,000, from a committee of village elders, who needed money to make improvements to the local schoolhouse. "There are always people in the villages who want to sell," Oungoyba says. "It's just a question of how much money."

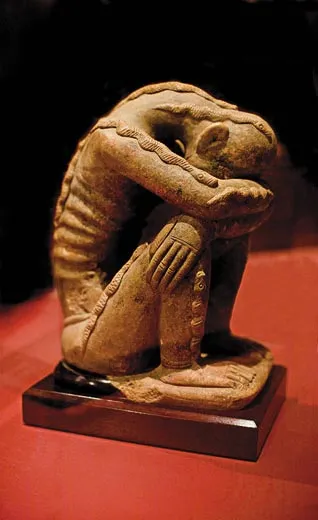

The villages of Dogon Country are among hundreds of sites across Mali that local people have plundered for cash. The pillaging feeds an insatiable overseas market for Malian antiquities, considered by European, American and Japanese art collectors to be among the finest in Africa. The objects range from the Inland Niger Delta's delicate terra-cotta statuettes—vestiges of three empires that controlled Saharan trade routes to Europe and the Middle East for some 600 years—to Neolithic pottery to the carved wooden doors and human figurines made by the Dogon.

According to Malian officials, skyrocketing prices for West African art and artifacts, along with the emergence of sophisticated smuggling networks, threaten to wipe out one of Africa's greatest cultural heritages. "These [antiquities dealers] are like narcotraffickers in Mexico," says Ali Kampo, a cultural official in Mopti, a trading town in the Inland Niger Delta. "They're running illegal networks from the poorest villages to the European buyers, and we don't have the resources to stop them."

Mali's antiquities are protected—in principle. The 1970 Unesco Convention signed in Paris obligated member nations to cooperate in "preventing the illicit import, export and transfer of ownership of cultural property." Fifteen years later, Mali passed legislation banning export of what is designated broadly as its cultural patrimony. But the laws have proved easy to circumvent. It's not just poor villagers who have succumbed to temptation. About a decade ago, according to unconfirmed reports, thieves made off with the central door of the Great Mosque of Djenné, a market town in the Inland Niger Delta. The centuries-old wooden door, inlaid with gold, allegedly disappeared while it was being replaced with a facsimile to thwart a plot to steal it. The door, which may well have fetched millions of dollars, was likely smuggled out of the country overland, across the porous border with Burkina Faso.

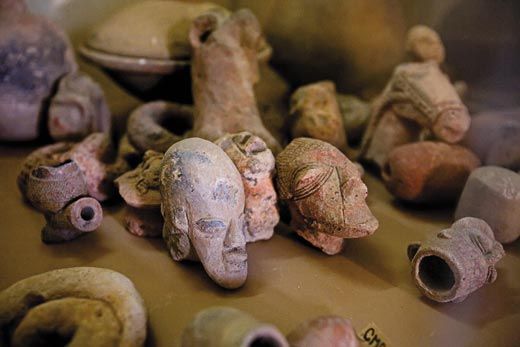

Antiquity thefts since then have continued apace. In November 2005, officials at France's Montpellier-Méditerranée Airport intercepted 9,500 artifacts from Mali. Days later, French customs agents outside Arles stopped a Moroccan truck bound for Germany packed with fossils from Morocco and statues, pottery and jewels from Mali. In January 2007, authorities at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris opened nine suspicious-looking packages marked "handcrafted objects" from Bamako, Mali's capital: inside they found more than 650 bracelets, ax heads, flint stones and stone rings, excavated from Neolithic settlement sites around Ménaka in eastern Mali. Some of these sites date back 8,000 years, when the Sahara was a vast savanna populated by hunter-gatherers. "When you tear these objects out of the ground, that's the end of any story we can reconstruct about that site in the past, what it was used for, who used it," says Susan Keech McIntosh, an archaeologist at Rice University in Houston and a leading authority on ancient West African civilizations. "It's a great loss."

I met up with McIntosh in Gao, a parched Niger River town of mud-walled houses and domed tents. The sun was setting over the Sahara when I arrived after a two-day drive across the desert from Timbuktu. McIntosh was there to look in on the excavation of a brick-and-stone complex being conducted by her graduate student, Mamadou Cissé. Locals believe that the site, constructed on top of more ancient structures, was built in the 14th century by Kankou Moussa, ruler of the Mali Empire. I found her seated on the concrete floor of an adobe-and-stucco guesthouse owned by Mali's culture ministry, adjacent to the municipal soccer grounds. With a 40-watt bulb providing the only illumination, she was studying some of the thousands of pottery fragments found at the site. "We've gone down nearly 12 feet, and the pottery appears to go back to around 2,000 years ago," she said, fingering a delicate pale blue shard.

In 1977, McIntosh and her then-husband, Roderick McIntosh, both graduate students in archaeology at the University of California at Santa Barbara, carried out excavations at a 20-foot-high mound that marked the site of Jenne-Jeno, a roughly 2,000-year-old commercial center along the ancient gold-trade route from Ghana and one of the oldest urban centers in sub-Saharan Africa, near present-day Djenné. The couple found pottery and terra-cotta sculptures embedded in clay, along with glass beads from as far away as Southeast Asia. The find was highly publicized: a Times of London correspondent reported on the excavations, and the McIntoshes documented their findings in the journal Archaeology. Meanwhile, the archaeologists also published a monograph on their work, illustrated by photographs of terra-cotta treasures they uncovered in 1977 and 1980, including a headless torso now on display at Mali's National Museum. A demand for figurines of similar quality was one factor in increased looting in the region, which had begun as far back as the 1960s.

From the 1980s on, she says, thieves ransacked hundreds of archaeological mounds in the Inland Niger Delta and elsewhere. The objects from these sites fetched extraordinary prices: in New York City in 1991, Sotheby's auctioned a 31 1/4- inch-tall Malian terra-cotta ram, from 600 to 1,000 years old, for $275,000—one of the highest prices commanded to that date for Malian statuary. (A Belgian journalist, Michel Brent, later reported that a Malian counterfeiter had added a fake body and hind legs to the ram, deceiving the world's African art experts. Brent also charged that the piece had been pillaged from the village of Dary in 1986.) In another notorious case, in 1997, then French President Jacques Chirac returned a terra-cotta ram he had received as a gift after Mali provided evidence that it had been looted from the Tenenkou region.

With a fierce wind blowing from the desert, I venture beyond Gao to observe examples of the systematic looting in the region. Mamadou Cissé, McIntosh's graduate student, leads me across an archaeological mound known as Gao-Saney. Grains of sand nip at our faces as we trudge across the 25- to 30-foot-high mound, crunching shards of ancient pottery beneath our feet. Below us, on the flood plain, I can make out the long dry bed of the Telemsi River, which likely drew settlers to this site 1,400 years ago. What commands my attention, however, are hundreds of holes, as deep as ten feet, that pockmark this mound. "Watch out," says Cissé, hopscotching past a trough gouged out of the sand. "The looters have dug everywhere."

Between A.D. 610 and 1200, Gao-Saney served as a trading center controlled by the Dia dynasty. A decade ago, Western and Malian archaeologists began digging in the sandy soil and uncovered fine pottery, copper bracelets and bead necklaces strung with glass and semiprecious stones. Looters, however, had already burrowed into the soft ground and sold what they found to international dealers in Niger. Several years ago, Mali's culture ministry hired a guard to watch the site around the clock. "By then it was too late," Cissé told me, surveying the moonscape. "Les pilleurs had stripped it clean."

The late Boubou Gassama, director of cultural affairs in the Gao region, had told me that looting had spread up the Telemsi Valley to remote sites virtually impossible to protect. In October 2004, local tipsters told him about a gang of pilleurs who were active in a desert area outside Gao; Gassama brought in the gendarmerie and conducted a predawn sting operation that netted 17 looters, who were making off with beads, arrowheads, vases and other objects from the Neolithic era and later. "They were mostly looking for glass beads, which they can sell in Morocco and Mauritania for as much as $3,000 apiece," Gassama had said. The men, all of them Tuareg nomads from around Timbuktu, served six months in the Gao prison. Since then, Cissé reports, locals have created "brigades of surveillance" to help protect the sites.

The Malian government has made modest progress combating antiquities theft. Former President Alpha Oumar Konaré, an archaeologist who held office between 1992 and 2002, established a network of cultural missions across the Inland Niger Delta, responsible for policing sites and raising awareness of the need to preserve Mali's heritage. The government also beefed up security at important mounds. McIntosh, who usually returns to Mali every couple of years, says Konaré's program has almost eliminated looting in Jenne-Jeno and the surrounding area.

Samuel Sidibé, director of Mali's National Museum in Bamako, has helped Mali's customs officials prevent cultural heritage material from leaving the country. Regulations require anyone seeking to export Malian art to submit the objects themselves—as well as a set of photographs—to museum officials. Sidibé and other experts issue export certificates only if they determine that the objects are not, in fact, cultural patrimony. Only two months earlier, Sidibé told me, he had been able to block a shipment of centuries-old terra cottas. Shady exporters are furious about the regulations, he adds, because they make it more difficult for them to pass off copies as authentic artifacts, and prices have nose-dived.

Oungoyba, the illegal antiquities dealer, scoffs at the regulations. I asked him if I would be able to smuggle Dogon sculptures out of the country. "Pas de problème," he says, flashing a small smile. Oungoyba says that he'll pack up whatever I purchase in a secured wood crate, and he instructs me to undervalue the purchase by 95 percent. Bamako International Airport, he says, can be tricky; he advises his clients to carry their purchases overland to Niger. Malian customs officials at the border usually can't be bothered to open the crate. "Just tell them that you spent $100 on it as a gift for your family, and nobody will ask questions," he assures me, adding that suspicious officials can be bought off. Once I've crossed into Niger, he continues, I'll be home free. The Niger government has been lax about enforcing the Unesco treaty obliging signatories to cooperate in combating antiquities theft. Oungoyba insists that his black-market trade helps the economy of the destitute Dogon region. But others say dealers and buyers hide behind such arguments to justify the damage they're inflicting on the culture. "They claim they're doing good things—building hospitals, spreading money around," Ali Kampo, the cultural official in Mopti, tells me. "But in the end, they're doing a disservice to humanity."

Writer Joshua Hammer lives in Berlin. Photographer Aaron Huey works from his base in Seattle, Washington.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)