Magic Kingdom

Within the Adriatic fortress of Dubrovnik, cafés, churches and palaces reflect 1,000 years of turbulent history

The fisherman had set the nets the night before and now, as the cathedral bells began to chime the start of a new day, they steered the small dory through Dubrovnik’s harbor gate and into the Adriatic. The boat turned into the wind and churned along the massive city wall that 12 centuries before with- stood a 15-month siege by marauding Saracens. Off to port loomed the pine-forested island of Lokrum, where King Richard I of England, the Lion Heart, was rescued from a shipwreck, it is said, while returning from the Third Crusade in 1192.

“Sometimes out here I feel as if I’m living five centuries ago,” said Nino Surjan, 60, as he slowly began hauling in nets studded with small tuna. “Kids today learn about Croatia, but when I was growing up we studied the Republic of Dubrovnik—a magical place that survived more than a thousand years without an army or a king.”

When the foredeck was littered with fish, Surjan produced a bottle of rakija (a plum brandy), took a generous gulp and handed the flask to Miho Hajtilovic, who leaned on the tiller and turned the vessel toward home. Time seemed to flow backward as the dory puttered past Renaissance palaces, the domes of Gothic churches and the medieval redoubt of Lovrijenac, outside the city walls, guarding the seaward approach to the city.

History resides everywhere here. “I was a child during the Italian occupation of parts of Croatia in World War II, and I still remember when the Partisans won that war,” the 71-yearold helmsman said. “Today, Tito’s communism seems to have vanished in the wind. I think it’s easier for people who have a past to put their lives in perspective.”

While Surjan coiled the nets, Hajtilovic loaded the fish onto a small dolly and manuevered it through the narrow harbor gate to the morning market in Gundulic Square . Already, sidewalk cafés along Stradun, the main pedestrian way, were filling with people absently watching clerics, tradesmen and professionals scurry to work. Up a narrow lane, a group of children straggled past a 16th-century church.

“In many respects, the 4,000 people living within Dubrovnik’s old city walls function as they did hundreds of years ago,” said Nikola Obuljen, 64, president of Dubrovnik’s city council, as he ambled across a limestone thoroughfare polished by centuries of foot traffic. “Venice has palazzos and the RialtoBridge, but Dubrovnik is a functioning Renaissance city where people live in the houses and shop at the markets.”

I first came to Dubrovnik in 1999 as a visitor searching for an eye in the Balkan storm. Kosovo then was in flames; Belgrade under siege. Bosnia remained intact only by force of international fiat. I needed a respite from Sarajevo, where, working as a journalism instructor, I happened to live a mile from a mass grave. That devastated city was recovering from the war that had ended there only the previous year. But as I drove south from Sarajevo toward Dalmatia, Bosnia’s once-fertile farmland offered only a succession of ghostly hamlets ethnically cleansed of inhabitants. Mostar, the last major stop before the Dinaric Alps, had been reduced to rubble. The Ottoman bridge that for centuries had spanned the NeretvaRiver was destroyed, a casualty of the malignant xenophobia then infecting Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But as I traveled down the coastal highway beyond the mountains, the air began to warm, scenes of destruction grew less frequent and police actually began to smile. At the village of Ston, gateway to the PeljesacPeninsula, I entered the old, 530-square-mile Republic of Dubrovnik, which enjoyed an independent status for a millennium, to 1808. For the next hour, I meandered past fishing villages nestled beneath foothills verdant with vineyards. In the distance, an archipelago seemed to float in the mist. And then it appeared in the twilight: a walled city rising from the rocky coast like an Adriatic Camelot.

Dubrovnik was founded at the start of the seventh century amid the chaos that followed the fall of the Roman Empire. Its first residents were refugees from Epidaurus, a Roman settlement farther down the Adriatic coast that had been overrun by invaders. To escape, the Romans moved to a forested, stony island separated from the coast by a narrow channel. They called the settlement Ragusium, derived from a word for rock. Croats, invited to Dalmatia by the emperor Heraclius to help fight the barbarians, soon joined them. Their name for the town was Dubrovnik, from an old Slavic word for woodland.

It was a propitious location. Midway between Venice and the Mediterranean, the city—its name now shortened to Ragusa— also lay on the east-west axis between Catholic Rome and Orthodox Byzantium. Washed by the prevailing sirocco (south wind) that drives ships north toward Venice, it was a natural port of call. It also was the terminus of the caravan route from Constantinople. As trade increased, the city’s strategic importance grew. For Renaissance popes, the Christian Republic of Ragusa proved a vital bulwark against advancing Islam. Ottoman sultans, on the other hand, viewed the town as a vital link to Mediterranean markets for their Balkan provinces.

Renaissance palaces, ecclesiastical treasuries and medieval libraries may be the city’s most impressive attractions, but the soaring city wall is Dubrovnik’s most imposing feature. Protected by two freestanding forts, the wall, more than a mile in circumference, surrounds the old city and contains five round towers, 12 quadrilateral forts, five bastions and two corner towers. The wall is a magnet for first-time visitors who, for the equivalent of $2 (15 kuna), can spend the entire day on the battlements gazing out on the Adriatic, peering down into convent cloisters or contemplating 1,400-foot MountSrdj to the north while sipping cappuccino atop a crenellated turret.

After Venice’s failed attempt to breach the walls in the tenth century, Dubrovnik was not seriously threatened again until 1806, when Russians and French fought over the city during the Napoleonic wars. The French finally commandeered it in 1808.

“Those stone balls aren’t for cannon; they were made to drop on invaders,” says Kate Bagoje, an art historian and secretary- conservator of the Friends of Dubrovnik Antiquities, a civic association that maintains the city walls. “And those slits in the wall,” she adds, striding across a parapet on the fort of Lovrijenac, “were for pouring down hot oil.”

Ironically, the strength of old Ragusa lay not in its ramparts but in the Rector’s Palace; from here, the aristocracy governed their republic through a series of councils. Surrounded by greedy empires and quarrelsome city-states, the city leaders had two great fears: being occupied by a foreign power or dominated by a charismatic autocrat who might emerge from their own noble families. To ensure against the latter, they invested executive power in a rector who, unlike the Venetian doge, who was elected for life, could serve for only one month, during which time his peers kept him a virtual prisoner. Garbed in red silk and black velvet and attended by musicians and palace guards when his presence was required outside the palace, the rector was accorded tremendous respect. But at the end of the month, a member of another noble family unceremoniously replaced him.

Maintaining independence was a more challenging task. Save for a few salt deposits on the mainland at Ston, the tiny republic had no natural resources. Its population was not large enough to support a standing army. Ragusa solved the problem by turning its brightest sons into diplomats and regarding the paying of tribute as the price of survival.

Diplomacy was key. When Byzantium faltered in 1081 and Venice became a threat, Ragusa turned to the South-Italian Normans for protection. In 1358, after Hungary expelled Venice from the eastern Adriatic, Ragusa swore allegiance to the victors. But when the Ottoman Turks defeated Hungary at the battle of Mohacs in 1526, Ragusa persuaded the sultan in Constantinople to become its protector.

In 1571, the republic faced a dilemma, however, when the Turkish navy sailed into the eastern Mediterranean, captured Cyprus and began attacking Venetian possessions. The Holy League, consisting of Pope Pius V, Spain and Venice, responded by sending its fleet to meet the Turks off the Greek city of Lepanto. Both sides expected Ragusa’s support, so— the story goes—the republic, exhibiting the kind of flexibility that would keep it independent for more than 1,000 years, sent emissaries to each. In the subsequent battle, the Holy League crushed Turkish naval power in the Mediterranean. But Ragusa had made sure it would be on the winning side—a status that would last until the republic lost its independence in 1808 to the French.

Located between the bell tower and steps leading up to the Jesuit College, Dubrovnik’s Rector’s Palace is the most beautiful example of secular Renaissance architecture in the eastern Adriatic. Now a museum, it was built in 1436 on the ruins of a medieval château, itself erected atop a Roman foundation. “Zagreb has commerce and politics, but Dubrovnik values art and culture,” said curator Vedrana Gjukic Bender as she pointed out the artworks adorning the Rector’s study. “This painting, the Baptism of Christ by Mihajlo Hamzic, commissioned in 1508, has never left the palace.

“There’s a portrait of Saint Blaise,” she continued, entering a second-floor reception area. “He is usually depicted with a wool-carding comb, because that’s what the Roman governor Agricola used to flay him in the third century. He became our patron saint in 972, when, according to legend, he appeared in a dream to warn a local priest of an imminent attack by the Venetians. Believing this sign to be true, the authorities armed the citizenry, who repulsed the assault.”

The nobility’s greatest legacy, however, is not spiritual rectitude but a sense of civic propriety, vestiges of which are everywhere. Above the doorway linking the Rector’s Palace with the building once used by the Grand Council is a carved inscription in Latin, which translates as “Forget private business, care for public affairs.” In the central archway of the Sponza Palace, where a scale hung when the building was the customshouse and mint, is the declaration, “Our weights prohibit cheating and being cheated. When I weigh the merchandise, God himself weighs the merchandise with me.”

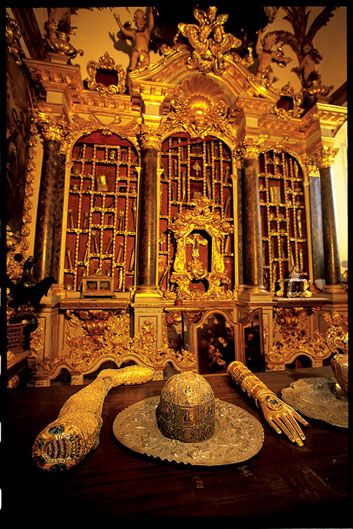

By the 16th century, Ragusa had become one of Europe’s leading city-states. Together with its eternal rival Venice, it was a major center of art, banking and culture. The city had 50 consulates positioned throughout Mediterranean Europe, Africa and the Near East. Its fleet of galleons and carracks was the third largest in the world behind those of Spain and the Netherlands.Many of the ships carried wool from Bulgaria, Serbian silver, or leather from Herzegovina. But some transported a more unusual cargo—religious relics, examples of which today can be seen in Dubrovnik’s Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin. It contains one of the most remarkable reliquaries in Christendom.

“Each relic has a separate story,” said 33-year-old art historian Vinicije Lupis, as he snapped open his briefcase, ceremonially extracted a pair of white cotton gloves and surveyed a room filled with jawbones, femurs, skulls and tibias encased in bejeweled golden containers. “That’s the lower jaw of Saint Stephen of Hungary,” he added, pointing to a wizened object on a platter. “Here, the left hand of Saint Blaise, given to Dubrovnik by Genoa.”

Profits from trade were not all spent on relics. The aristocracy may have been grounded in feudalism, but it gave all children in its stratified society access to public schools. It provided health care, established one of Europe’s first orphanages and, in 1416, when the slave trade was ongoing in the region, adopted antislavery laws.

Dubrovnik continues to benefit from civic improvements made centuries ago. Fresh water from a system of pipes installed in the Middle Ages still burbles from two fountains at either end of the main street of Stradun. Situated outside the eastern gate on the old caravan road to Bosnia, the 16th-century quarantine hospital built to prevent the spread of plague remains in such good condition that today it is used for art exhibitions.

From its beginning, Dubrovnik was a city of refuge and diversity. When the Spanish monarchy expelled Jews in 1492, many found new homes a few steps up from Stradun on Zudioska Street , where one of the oldest Sephardic synagogues in Europe is located. Serbs, too, were welcomed after their 1389 defeat at Kosovo Polje, much to the distress of the Turks.

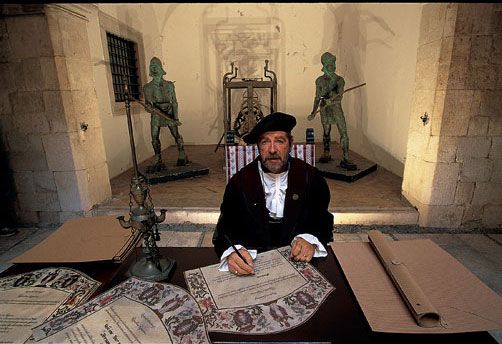

Dubrovnik was not only a sanctuary for exiles but also a repository for Central European history. “The parchment and inks produced here have not faded in 800 years,” said Stjepan Cosic, a 37-year-old research associate with the Institute for History and Science. “This paper is bright white because it contains no wood-pulp cellulose; it was made from cotton fabric. The inks, based on a mixture of iron, ashes and acorns, remain as vivid as the day they were put to paper.”

If history seems alive to Cosic, perhaps it’s because he works in a 1526 waterfront palace with 18-foot ceilings, rooms filled with more than 100,000 manuscripts and a boathouse sized to accommodate a trading vessel. “Croatia is a small country with only 4,000,000 people. Dubrovnik’s population is only 46,000. But the essence of our country’s history and culture resides in Dubrovnik,” he says.

For centuries, Ragusa survived plague, coexisted with Ottomans and kept papal intrigues at arm’s length, but there was no escape from nature. On the Saturday before Easter in 1667, a massive earthquake reduced the city to rubble. Gone in an instant were most of the Gothic monasteries, the Romanesque cathedral and many of the Renaissance palaces. Towering waves poured in through an enormous fissure in the city wall, flooding a portion of the town, while fire ravaged what remained. Of the city’s 6,000 residents, at least 3,500 were killed, many of them nobility.

The aristocracy rebuilt their city. Alittle more than a century later, at the close of the American Revolutionary War, Ragusan carracks even called at ports as distant as New York, Philadelphia and Baltimore. But the power of Mediterranean city-states was waning. Though Ragusa remained the capital of an independent republic for another quarter century, its thousand years of freedom ended in 1808, when Napoléon, moving inexorably eastward, annexed Dalmatia.

After the defeat of Napoléon, the Congress of Vienna incorporated Ragusa and the rest of Dalmatia into the Austro- Hungarian Empire, where it remained for a century. In June 1914, a young Serb nationalist, Gavrilo Princip, assassinated the heir to the Hapsburg throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo. At the conclusion of World War I, Princip’s dreams were realized when the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes—later renamed Yugoslavia—was created. After World War II, Yugoslavia became a communist republic under the leadership of Josip Broz, a Croat known as Tito.

The BaroqueCity seen by visitors today features a few Renaissance buildings that predate the earthquake. But Dubrovnik’s greatest treasure is its archive. In vaulted rooms on the second floor of the SponzaPalace are thousands of pristine, perfectly legible documents dating back more than eight centuries. “The Venice archives are exclusively political, but ours cover every aspect of life,” said archivist Ante Soljic as he extracted a medieval dowry contract from a folder bound with velvet ribbon. “We have virtually the complete economic history of the republic, 1282 to 1815, seen through real estate transactions, leasing agreements, customs documents and court records.

“We have records in Latin, Hebrew, Medieval Greek and Bosnian Cyrillic script,” Soljic continued. “We also have more than 12,000 Turkish manuscripts, many of them beautiful works of art.”

Not all of the city-state’s history is readily accessible. A 1967 guide to Dubrovnik touts the Museum of the Socialist Revolution in the SponzaPalace, with exhibits on the history of Dubrovnik’s Communist Party and Nazi persecution of Tito’s Partisan army. Today, one looks in vain for that museum. The receptionist at the palace hasn’t heard of it. Only Ivo Dabelic, Dubrovnik’s curator of recent history, knows the location of Dalmatia’s revolutionary past. And he’s glad somebody asked him where it is.

“Don’t worry, the exhibits are safe,” he said when we met at Luza Square . “Just follow me.” Crossing the square to the Rector’s Palace, Dabelic entered a room where a portion of the wall sprang open, revealing a hidden cupboard. “Ah, here it is,” he said, removing a large iron key. We made our way back to awooden door at the palace’s rear. “The Socialist museum was closed in 1988; we intended to display the items in a lending library,” Dabelic said as we inched down a stairway. “But when the [Serbian] Yugoslav army began shelling the city in 1991, things got very confused.

“There they are,” he said, shining a flashlight on a stack of wooden boxes set in the middle of a subterranean cell. “All the helmets, photos and documents of the socialist era,” he said. “Dubrovnik has the resources for a museum of contemporary history, but the city prefers to spend its money on the Summer Festival.”

Until well into 1992, the Yugoslav army pounded Dubrovnik with artillery. By the time the shelling stopped, 382 residential, 19 religious and 10 public buildings were seriously damaged, along with 70 percent of the city’s roofs. The lives of 92 people were also lost.

“There were banners all over the city proclaiming Dubrovnik a World Heritage Site under protection of UNESCO, but they were ignored,” recalled Berta Dragicevic, executive secretary of the InterUniversityCenter. “The archives were saved, but 30,000 books, many irreplaceable, were reduced to ashes.”

Today, extensive restorations have been completed. The city’s bas-relief friezes, lancet windows and terra-cotta roofs largely have been repaired, but much work remains. “Progress is slow because we’re using construction techniques that are centuries old,” said Matko Vetma, the director of a private company restoring the city’s 14th-century Franciscan monastery. “The stonecutters who are replacing the rose windows in the cloister possess the skills of Renaissance artisans.” Fortunately, the workers are not limited to Renaissance materials. “We’re reinforcing the walls with steel beams and epoxy,” Vetma added. “At least the friars won’t have to worry as much about earthquakes in the future.”

Dubrovnik today spends 20 percent of its budget on culture. During the Summer Festival in July and August, the entire walled city becomes an open-air stage. Plays, concerts and folk dances are performed at 30 venues, including intimate market squares, the foyers of Renaissance palaces and the ramparts of medieval fortifications.

“Performing in the open air is different than inside a small theater,” said 76-year-old Mise Martinovic, the dean of Dubrovnik actors. “There are silent nights when the air is dead calm. And nights when electricity from an approaching storm makes your hair tingle.

“I remember when Marshal Tito and the King of Greece came to see Hamlet and remained seated during a violent storm,” Martinovic reminisced. “It was pouring rain; one by one the stage lights began to explode. But they never moved.”

After a final glance at the fortress of Lovrijenac, Martinovic finished his coffee and rose to resume his morning walk. “Dubrovnik is haunted by invisible forces from the past,” he mused. “On a silent night you almost can hear the ghosts. There is magic in this city.”

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.