Malibu’s Epic Battle of Surfers Vs. Environmentalists

Local politics take a dramatic turn in southern California over a plan to clean up an iconic American playground

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Breaking-Point-Malibu-631.jpg)

When a swell approaches Malibu’s most famous beach, Surfrider, it begins breaking just above a long, curved alluvial fan of sediment and stones near the mouth of Malibu Creek. It then flattens out, rears up again and rounds a small cove before running toward the shore for 200 yards. Here, according to Matt Warshaw’s book The History of Surfing, it “becomes the faultless Malibu wave of legend”—a wave that spawned Southern California surf culture. The plot of the classic 1966 movie Endless Summer was the quest for, in the words of the film’s director-narrator, “a place as good as Malibu.” In 2010, Surfrider was designated the first World Surfing Reserve.

Stephenie Glas moved to this stretch of Los Angeles County in the late 1990s. Blond, athletic and in her mid-20s at the time, she settled in a Malibu neighborhood with gaping ocean views and took to the water with her kiteboard. “She was one of the very few women that would hit the lip [of waves] with style,” an acquaintance of hers observed. “No holding back!”

Always something of an over-achiever, Glas had worked her way through UCLA by starting a personal-training business, and later set her sights on becoming a firefighter. In 2005 she joined the Los Angeles Fire Department, a force that was 97 percent male. “I picked this career knowing I would have to spend the next 25 years proving myself to men,” Glas said in a magazine profile.

To what extent her hard-charging nature contributed to her becoming a polarizing figure in close-knit Malibu is open to question. But she dove into one of the most surprising environmental disputes in memory not long after her partner, a 55-year-old goateed carpenter and surfer named Steve Woods, contracted a gastrointestinal illness following a session at Surfrider.

The water there, everyone knew, was contaminated with runoff from commercial and residential developments as well as effluent that flowed out of a wastewater treatment plant through Malibu Creek and into Malibu Lagoon before pulsing into the ocean. Eye, ear and sinus infections and gastrointestinal ailments were common side effects of paddling out at Surfrider. In the late 1990s, four surfers died after contracting water-borne diseases, reportedly acquired in the sludgy waves, and a fifth was nearly killed by a viral infection that attacked his heart.

UCLA scientists commissioned a study in the late 1990s and found a “stagnant lagoon replete with human waste and pathogens,” including fecal contamination and parasites such as Giardia and Cryptosporidium. California’s Water Resources Control Board in 2006 found numerous violations of water quality standards. A federal judge ruled in 2010 that the high bacteria levels violated the federal Clean Water Act. “Malibu Creek is a watershed on the brink of irreversible degradation,” warned Mark Gold, then the director of the nonprofit Heal the Bay.

One government authority after another approved an ambitious plan to rehabilitate the lagoon, to improve water flow and quality and bring back native wildlife. Combining historical data and modern scientific methods, the plan emphasized a return to the lagoon’s original functions, recreating a buffer against rising sea levels, a nursery for fish and a stopover for birds on the Pacific Flyway migration route. This was in contrast to previous wetlands restorations in Southern California—including a failed one at Malibu Lagoon in 1983—which had altered original ecosystems, imperiling fish and birds. When the Malibu Lagoon plan was approved, it set a new precedent. “We can get ecological functions back or put them in place by giving a system the bones that it needs, the water flow, the land flow, the elevations that we know are useful,” Shelley Luce, director of the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission, a nonprofit overseeing the work, said of the plan’s emphasis on historical accuracy.

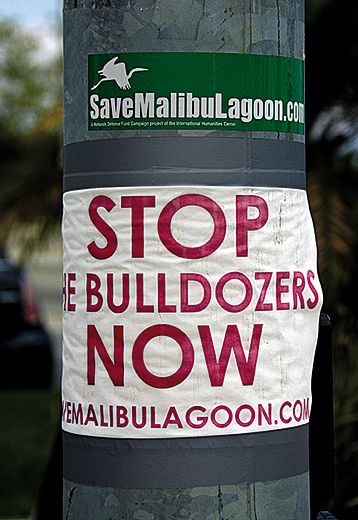

Then something unexpected happened, something seemingly out of character for a place that prides itself on its natural lifestyle: People vehemently opposed the cleanup. Surfers said tampering with the lagoon would wreck the legendary waves at Surfrider. Real estate agents said the construction mess would deprive them and property owners of rental income, beach houses in the area going for up to $75,000 a month. One environmental group insisted restoring the lagoon would do more harm than good. Protesters on the Pacific Coast Highway held signs that drivers whizzing by might have been puzzled to see in this sun-drenched idyll—“Malibu Massacre,” one said. Debate erupted on the local news website Malibu Patch, with people on both sides of the issue taking aim at one another in increasingly angry posts.

Some of Malibu’s famous residents jumped in. Anthony Kiedis, lead singer of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, said in an interview tied to an anti-restoration fundraiser: “Not being a biologist or a politician, I just kind of had to go with my gut instinct. Obviously [Malibu Lagoon is] not pristine, but it’s also not a toxic waste dump....The idea of bulldozing it and replacing it with an artificial version—just common sense tells me that’s not a good idea.” “Baywatch” star Pamela Anderson posted a note on Facebook with a racy photo of herself sitting by a river: “Why are they dredging up the Malibu Lagoon...? It is a protected wetland and bird sanctuary...”

In some ways the debate was classic Nimbyism, a case of locals not wanting outsiders to change the paradise they had come to love. But in other ways the Malibu controversy has been exceptional, a crack in the surface of an iconic American playground that reveals other, deeper forces at work: the fierceness of surf culture at its most territorial, property interests allied against environmental reformers and scientists, the thrall of Hollywood celebrity.

Glas, for her part, was fairly shocked by what she saw as a misunderstanding of the scientific issues. So she co-founded a website, TheRealMalibu411, and tried to explain the complex environmental plans. “Stephenie and I wanted to leave the emotion out and just deal with the facts,” Woods said. “If you make a claim, bring the facts on the table. Let’s put your facts with our facts.”

The emotions, though, were front and center, along with invective hurled at Glas because of her visible role as an advocate for the cleanup. One local called her a “man chick”; others said she was a liar. You might think a person who fought fires for a living would brush off the insults, but to hear Woods tell it, she was upset. And as she devoted more of her free time to the cause, typing late-night e-mails and online comments between intense, often dangerous shifts at work, she became increasingly distressed.

Then, one day this past February, Glas drove up the coast to Oxnard and purchased a handgun.

***

Malibu Creek originates on the flanks of 3,111-foot Sandstone Peak, the highest point in a range of mountains that sequesters Malibu from the rest of Los Angeles. The creek descends through rolling foothills into what was once a sprawling wetlands with a large estuary and lagoon. In prehistoric times, the Chumash Indians built a village near the creek mouth, where shallow waters teemed with steelhead trout. “Malibu” is a mispronunciation of the Chumash word Humaliwo, “where the surf sounds loudly.” Like other coastal wetlands, the Malibu Creek and Lagoon managed floodwaters and served as a giant natural recycling system, channeling rainwater and decomposing organic materials. Jackknife clams, tidewater goby fish, egrets and thousands of other species thrived.

By the time modern development kicked into high gear during the westward expansion of the early 1900s, the ecosystem was gravely misunderstood. “They didn’t know what the wetland function is,” Suzanne Goode, a senior environmental scientist with California’s Department of Parks and Recreation, told me one afternoon last summer as we stood on the edge of Malibu Lagoon. “They saw it as a swamp that’s full of bugs and maybe doesn’t smell good, and you can’t develop it because it’s all wet and mucky.”

When workers in the late 1920s carved the Pacific Coast Highway through the wetlands, tons of dirt sloughed into the western channels of Malibu Lagoon. Soon after, a barrier beach buffering the lagoon was sold off to Hollywood celebrities such as Gloria Swanson and Frank Capra, who plunked shacks into the sand to create a neighborhood known as the Malibu Movie Colony. This development was one of the first to choke the path of the creek and gobble up wildlife habitat.

At the same time, municipalities throughout Southern California began tapping the Colorado River and the San Joaquin Delta system, allowing the booming population to grow lawns and flush toilets. Much of this extra, imported water made its way to the ocean. Throughout the 1970s and ’80s, a wastewater treatment plant upstream from Malibu Lagoon released up to ten million gallons of lightly treated San Fernando Valley sewage daily. As of the 1989 North American Wetlands Conservation Act, which aimed to provide funding to manage wetland habitats for migratory birds, 91 percent of the wetlands in California—and half of those in the United States—had been obliterated.

The lagoon cleanup plan was designed to enable the wetlands to purge itself naturally. To that end, the westernmost channels would be drained of contaminated water, and bulldozers would dredge the excess sediment from that area. The machines would then remove invasive species and regrade a portion of the lagoon to allow water to circulate more easily. Eventually the native plants and animals that had been temporarily relocated would be returned.

In the Malibu Lagoon controversy, which had hijacked local politics by 2011, the dissenters were maybe 150 to 200 people—a small percentage of the city’s nearly 13,000 residents—but they were vocal. At one city council meeting, a surfer and real estate agent named Andy Lyon, who grew up in Malibu Colony, launched into an explosive tirade about the threat to the surf break. He shouted into the microphone as council members struggled to regain decorum; they eventually summoned the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. “I don’t care! I’m going to surf!” Lyon yelled as he left City Hall. From then on, a sheriff’s deputy was assigned to the meetings. “It definitely got people’s attention,” Lyon later told me of his public speaking style. In last spring’s city council election, four candidates campaigned on an anti-cleanup platform; of those, a 28-year-old named Skylar Peak, who had vowed to chain himself to the bulldozers alongside his surfing buddy Lyon, was elected.

The city council, as some restoration opponents saw it, was failing to protect Malibu’s greatest asset: Surfrider break. Malibu surfers were a notoriously territorial bunch with a long history of bullying and even threatening violence against outsiders who dared to poach their waves. To them, jeopardizing the surf was the ultimate betrayal. “[The break] is like a historical monument. It should be protected above everything. Above the lagoon itself,” Lyon told me. “They talk about the Chumash Indians and all that other crap. The historical cultural value of Malibu as a surf spot should have been protected and they did zero.”

The exchanges on the Malibu Patch site devolved into vicious sparring matches. One opponent wrote: “Stephanie [sic] Glas wants to kill animals, birds, fish, nests, plant life, in order to help the fish and ‘water flow.’” She fired back by posting detailed scientific information about the project—and then calling her adversary a liar. Despite their original intention of maintaining a civil discourse, Woods and Glas were eventually barred from commenting on Patch.

So Glas created TheRealMalibu411, where she posted the official lagoon restoration plan, the environmental impact report, photographs and court documents. Glas got more heat. One night, she and Woods were at a local restaurant when a woman screamed at them, “ ‘F— you, animal killers! Get the f— out of Malibu! Nobody wants you here!” They weren’t the only targets. In early June, a California parks department worker was approached by a pair of surfers who asked whether he was involved in the lagoon restoration. “If you are, you will be wearing a toe tag,” the surfers warned. Soon after, Suzanne Goode, one of the project managers, received a voice mail: “You’re horrible, you’re a criminal, you should be ashamed of yourself. And we’re not through with you.” The opposition went on to nickname Goode “The Wicked Witch of the Wetlands.”

Glas “feared for her safety,” according to Cece Stein, Glas’ friend and co-founder of TheRealMalibu411. To be sure, Glas was also exhausted by the round-the-clock nature of her firefighting job and the grisly traffic accidents and crime—drug deals, overdoses, gang violence—it forced her to encounter. In 2008, she was a first responder at a deadly train crash in Chatsworth; she had to look for survivors among the bodies destroyed in the blaze. Glas developed a hard edge that may have undermined her in the Malibu Lagoon debate. But there was more to her than that. The opposition, Woods said, “didn’t know she was this delicate little flower inside.”

***

Roy van de Hoek set a pair of binoculars on the table as he and his partner, Marcia Hanscom, joined me at a bustling Venice Beach restaurant on a hot morning this past July. The couple, in their 50s, propelled the legal opposition to the Malibu Lagoon cleanup. Van de Hoek, tall and willowy with a gray ponytail and beard, is a Los Angeles County parks and recreation employee, and Hanscom, whose raven hair frames a round, ruddy face and bright brown eyes, operate half a dozen nonprofit environmental organizations. Members of the original lagoon task force, they initially supported the restoration. But then Hanscom, who has a degree in communications, and van de Hoek mobilized against the task force, with Hanscom establishing a nonprofit called the Wetlands Defense Fund in 2006 and four years later filing the first of a series of lawsuits to halt the project.

Hanscom and van de Hoek said they rejected the task force’s finding that the lagoon was oxygen depleted; the birds and fish were evidence of a thriving wetlands, they said. “Chemistry devices and electronic equipment don’t give you the overall picture [of the health of the lagoon],” said van de Hoek. As they see it, they are at the forefront of wetlands science, whereas restoration advocates “have a complete misunderstanding of what kind of ecosystem this is,” Hanscom told me. The dozens of active credentialed scientists who have contributed to the restoration effort would, of course, beg to differ.

It wasn’t the first time van de Hoek had challenged environmental policy. According to news reports, after he was fired from a job with the Bureau of Land Management in 1993 over a disagreement with its wildlife-management techniques, he cut down trees and removed fences from bureau property in Central California; he was arrested and convicted in 1997 of misdemeanor vandalism, for which he received three years’ probation. In 2006, he was arrested for destroying nonnative plants and illegally entering an ecological preserve, Los Angeles’ Ballona Wetlands; the case was dismissed. In 2010, he told the Argonaut newspaper that he had surreptitiously introduced a parasitic plant to the Ballona Wetlands in order to kill nonnative flora; biologists say it is now destroying many native plants.

Hanscom and van de Hoek’s con- cerns about the lagoon restoration included the use of bulldozers at the site. “Rare and endangered wildlife and birds will be crushed,” they wrote in a letter to California Gov. Jerry Brown. “Survivors will flee the fumes and deafening clatter never to return. It’s the Malibu Massacre.” An ad they placed in a local newspaper said, “The natural habitat you’ve known as Malibu Lagoon, our very own Walden Pond...will be far less habitable.”

To some observers, Hanscom and van de Hoek stoked the opposition for nonscientific reasons. “[Hanscom] found that there’s no money in supporting this project, but she could oppose it and get a lot of funds raised real fast,” said Glenn Hening, founder of the Surfrider Foundation, a nonprofit of 50,000 environmentally minded surfers. The group commissioned a 2011 report that determined the restoration would have no impact on Surfrider’s waves.

Hanscom and van de Hoek recruited Malibu’s wealthy, celebrity-filled population. According to Hanscom, the actors Pierce Brosnan, Martin Sheen and Victoria Principal were among those who made financial donations or wrote letters on behalf of the anti-restoration cause. Kiedis, the rock singer, attended a fund-raiser benefiting the couple’s nonprofits. In a 2010 newspaper ad, Hanscom and van de Hoek estimated the anti-restoration legal fight would cost $350,000. Hanscom told Los Angeles Weekly in mid-2011 that she had raised $150,000. The support went toward legal fees and environmental research for lagoon litigation, Hanscom said. She told me she was “financially in the hole” on the lagoon fight.

***

On June 4, a team of 60 workers began uprooting native plants and relocating animals in the first phase of the restoration project. A Chumash elder already had conducted a blessing ceremony of the lagoon waters. Later that day, Glas, Woods and their friend Cece Stein were holding signs on the bridge. “Restore Malibu Lagoon. It’s About Time.” “We Support a Healthy Lagoon.” A hundred yards away, near the entrance to Malibu Lagoon State Park, a group of 15 anti-cleanup activists solicited honks from passing drivers with their own signs. “Don’t Mess With Our Lagoon.” “Crime Scene.”

As Glas walked toward the park entrance en route to the bathroom, several protesters pounced. “They were hurling insults and profanity at her,” Woods told me. “They said, ‘You’re so f—— stupid.’” On her way back, the jeering intensified, prompting two park rangers to step in and escort Glas back to the bridge. When she rejoined Woods and Stein, she sat on the curb and broke into tears.

Over the next several days, Glas’ behavior grew odd and erratic, according to Woods and Stein. Her temper quickened and she was argumentative even with friends. Five nights after the lagoon protests, Woods and Glas had a seemingly mundane disagreement over whether to watch the Stanley Cup or a surfing competition on TV. But Glas was being irrational in the extreme, according to Woods. “She was trying to provoke me and push my buttons.” He stepped out of the house to get some air. Seconds later he heard a gunshot, and when he ran back inside, Glas was lying in the front hallway with her pistol nearby on the floor. She died later that night at a local hospital of what law enforcement authorities ruled a suicide by means of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head.

Woods acknowledged to me that Glas, 37, had had a history of depression and may have suffered from work-related post-traumatic stress disorder. But he insisted that tensions over the lagoon, specifically the harassment she endured near the bridge, had pushed her to her breaking point. “That was a stress she didn’t need,” Woods said.

The day after Glas’ death, Lyon wrote in an e-mail posted on Patch, “I’m shattered. Before all this b—— we were good friends....I have fond memories of [kiteboarding] with Steph and that is how I will always and only remember her.” He eventually challenged the suggestion that Glas’ suicide was linked to the lagoon debate. “If anybody’s going to put a gun in their mouth,” he told me, “it would’ve been me, given the amount of personal attacks I’ve taken for standing up to this thing.”

By early August, the work in the lagoon was 25 percent complete, with 48.5 million gallons of contaminated water having been drained and 3.5 tons of excess earth, utility poles and hunks of concrete removed. Numerous species, including the goby, and the nests of ducks, phoebes and coots were relocated to nearby habitat, to be returned in the fall, near the project’s scheduled October 15 end date.

Around this time, Hanscom and van de Hoek dropped the appeal of their initial lawsuit. “We felt that the odds were stacked against us in that particular venue,” Hanscom said. But they asked the California Coastal Commission to revoke the restoration permit. The commission produced an 875-page document denying the plea. “There’s not a single shred of evidence for us to entertain revocation,” one commissioner said. In testimony, an attorney for California’s parks department suggested that the commission request restitution from Hanscom and van de Hoek for the financial burden taxpayers had shouldered in defending against their lawsuits.

As summer gave way to fall, Woods and Stein continued the effort Glas had begun on TheRealMalibu411. They posted videotaped reports from the lagoon, interviewing the scientists overseeing the project and fact-checking the claims that kept rolling in from opposition members. They were also gearing up for the next big local environmental battle—the Malibu sewer debate. The city council is exploring plans to install Malibu’s first sewage treatment plant; some local residents support the measure as critically important for the environment while others oppose it, saying it would enable an onslaught of development.

Glas, Woods and their allies in the lagoon fight had seen the sewer as the next logical step in rehabilitating the local environment. “The day Stephenie died, we were talking about the lagoon project,” Woods said one afternoon, sitting in his Malibu living room, his green eyes pinched into a permanent squint from four decades of riding waves in the harsh sun. “The opposition had exhausted all legal options. There was nothing they could do now to stop it.” Woods suggested that Glas take a break before turning her attention to the sewer. Within minutes of the conversation, however, she was calling the city council and the state water board for sewer information. Woods urged her to take a rest. “I told her the lagoon issue was draining and exhausting, but that’s nothing compared to what this sewer thing is going to be. It’s a monster like you’ve never seen.”

“We need to clean up the water,” Glas said.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.