Marseille’s Ethnic Bouillabaisse

Some view Europe’s most diverse city as a laboratory of the continent’s future

One morning in early November 2005, Kader Tighilt turned on the radio as he drove to work. The news reported that 14 cars had burned overnight in Marseille's northern suburbs. "They've done it," Tighilt said out loud. "The bastards!" It seemed his worst fears had been confirmed: riots, which had first broken out in the suburbs of Paris on October 27, had now spread to the port city and one of the largest immigrant communities in France. For the previous two weeks, Tighilt, his fellow social workers and community volunteers had been working feverishly to prevent this very thing from happening, fanning out across the city to places where young people gathered to spread the word that violence was folly.

"We were worried that [our youths] would try to compete with Paris," says Tighilt, 45, who grew up in an Algerian family in a shantytown on the outskirts of the city. He was not alone. Marseille is not only arguably Europe's most ethnically diverse city, but also has as high a proportion of Muslims as any place in Western Europe. It suffers from high unemployment and the usual brew of urban problems. "We were waiting for the place to explode," one city official confided later.

But it didn't. Tighilt called a friend on the police force that morning, only to discover that the radio report had been exaggerated: yes, 14 cars had burned, but not in the Marseille suburbs alone—in the entire department, an area with a population of nearly two million people. By Paris' standards, the incident was trifling. And that was about it. For three weeks, riot police would fight running battles in the French capital, in Lyon, Strasbourg and elsewhere; dozens of shops, schools and businesses would be ransacked, thousands of cars torched and 3,000 rioters arrested. Yet Marseille, with a population of slightly more than 800,000, remained relatively quiet.

Despite being home to sizable Jewish and Muslim populations, Marseille had largely avoided the worst of the anti-Semitic attacks that swept France in 2002 and 2003 in the wake of the second intifada (Palestinian uprising) in Israel. And the 2006 Israeli incursion against Hezbollah in Lebanon produced anti-Israeli demonstrations in the city but no violence. At a time when disputes over the role of Islam in Western society are dividing Europe, Marseille has recently approved construction of a huge new mosque on a hill overlooking the harbor, setting aside a $2.6 million plot of city-owned land for the project. "If France is a very racist country," says Susanne Stemmler, a French studies expert at the Center for Metropolitan Studies in Berlin who has focused on youth culture in the port city, "Marseille is its liberated zone."

It seems an unlikely model. The city has not historically enjoyed a reputation for serenity. For Americans, at least, it may best be remembered as a setting for The French Connection, the 1971 drug smuggling thriller starring Gene Hackman. French television series depict the city as a seedy, rebellious enclave lacking in proper Gallic restraint. Yet its calm in the midst of a crisis has caused sociologists and politicians to take a fresh look. Across Europe, immigrant populations are mushrooming. There were fewer than one million Muslims in Western Europe after World War II before guest-worker programs fueled immigration. Today there are 15 million Muslims, five million in France alone. That change has exacerbated tensions between communities and local governments struggling to cope with the newcomers. Could Marseille, gritty yet forward-thinking, and as the French say, convivial, hold a key to Europe's future?

These questions come at a time when Marseille's image is already undergoing an upgrade. The world of drug lords and crumbling wharves has been giving way, block by block, to tourists and trendy boutiques. The French government has pledged more than half a billion dollars to redevelop the waterfront. Cruise ships brought 460,000 visitors this year, up from 19,000 a decade ago. Hotel capacity is expected to increase 50 percent in the next four years. Once merely the jumping-off point for tourists heading into Provence, the old port city is fast becoming a destination in itself. "Marseille is no longer the city of The French Connection," Thomas Verdon, the city's director of tourism, assured me. "It's a melting pot of civilizations."

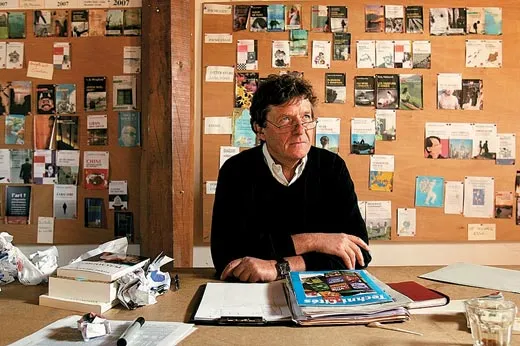

Fifty years ago, from Alexandria to Beirut to Algeria's Oran, multicultural cities were the norm on the Mediterranean. Today, according to French sociologist Jean Viard, Marseille is the only one remaining. As such, he says, it represents a kind of "laboratory for an increasingly heterogeneous Europe." It is, he adds, "a city of the past—and of the future."

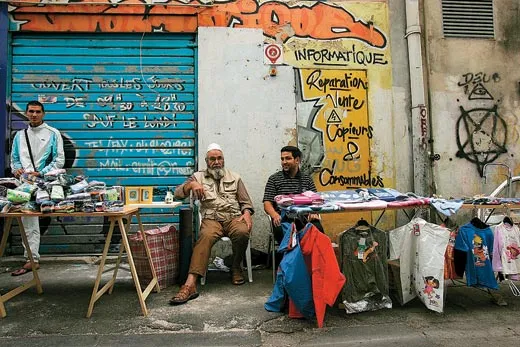

When I visited Marseille, in the waning days of a Provençal summer, a "three-masted" tall ship from a Colombian naval academy was moored in the inner harbor, sporting a display of flags from around the world and blasting samba music. At first glance, Marseille, with its jumble of white and brown buildings crowded around a narrow harbor, seems to resemble other port towns along France's Mediterranean coast. But less than half a mile from the historic center of the city lies the hectic, crowded quarter of Noailles, where immigrants from Morocco or Algeria, Senegal or the Indian Ocean's Comoro Islands haggle over halal (the Muslim version of kosher) meats as well as pastries and used clothing. Impromptu flea markets blanket sidewalks and back alleys. Just off the rue des Dominicaines, one of the city's older avenues, across from a shuttered 17th-century church, Muslim men kneel toward Mecca in a vacant shop lit by a single fluorescent bulb.

That night, the Colombian cadets were throwing a party. Thousands of Marseillais from the Arab world, as well as Armenians, Senegalese, Comorans and native French, descended on the Vieux Port to saunter along the waterfront or stop for a pastis (anise-flavored aperitif) at a local café. Some danced on the ship's deck. A shipboard band, not far from my hotel, played on until early morning. Then, as the first Vespas began roaring around the port-side boulevard at dawn, a lone trumpeter outside my window played "La Marseillaise." The national anthem, composed during the French Revolution, took its name from the city because it was popularized by local militias who sang the call to arms as they marched on Paris.

Of the city's 800,000 souls, some 200,000 are Muslim; 80,000 are Armenian Orthodox. There are nearly 80,000 Jews, the third-largest population in Europe, as well as 3,000 Buddhists. Marseille is home to more Comorans (70,000) than any other city but Moroni, the capital of the East African island nation. Marseille has 68 Muslim prayer rooms, 41 synagogues and 29 Jewish schools, as well as an assortment of Buddhist temples.

"What makes Marseille different," said Clément Yana, an oral surgeon who is a leader of the city's Jewish community, "is the will not to be provoked, for example, by the intifada in Israel—not to let the situation get out of control. We could either panic, and say 'Look, there is anti-Semitism!' or we could get out in the communities and work." Several years ago, he said, when a synagogue on the outskirts of Marseille was burned to the ground, Jewish parents ordered their kids to stay home and canceled a series of soccer matches scheduled in Arab neighborhoods. Kader Tighilt (who is Muslim and heads a mentoring association, Future Generations) immediately telephoned Yana. Virtually overnight, the two men organized a tournament that would include both Muslim and Jewish players. They initially called the games, now an annual affair, the "tournament of peace and brotherhood."

A spirit of cooperation, therefore, was already well established at the moment in 2005 when community leaders feared that Arab neighborhoods were about to erupt. Volunteers and staffers from a variety of organizations, including Future Generations, fanned out across Marseille and its northern suburbs attempting to put into context the then nonstop TV coverage of riots erupting in Paris and elsewhere in France. "We told them 'In Paris they are stupid'; 'They are burning their neighbors' cars'; 'Don't fall into that trap,'" Tighilt says. "I didn't want immigrant neighborhoods to be locked up and ghettoized," he recalled. "We have a choice." Either "we surrender these places to the law of the jungle," or "we take it upon ourselves to become masters of our own neighborhoods."

Nassera Benmarnia founded the Union of Muslim Families in 1996, when she concluded that her children risked losing touch with their roots. At her headquarters, I found several women baking bread as they counseled elderly clients on housing and health care. Benmarnia's aim, she says, is to "normalize" the presence of the Muslim community in the city. In 1998, to observe the holiday Eid al-Adha (marking the end of the pilgrimage season to Mecca), she organized a citywide party she dubbed Eid-in-the-City, to which she invited non-Muslims as well as Muslims, with dancing, music and feasting. Each year since, the celebration has grown. Last year, she even invited a group of pieds-noirs, descendants of the French who had colonized Arab North Africa and are believed by some to be particularly hostile to Arab immigrants. "Yes, they were surprised!" she says. "But they enjoyed it!" One-third of the partygoers turned out to be Christians, Jews or other non-Muslims.

Though a devout Catholic, Marseille's mayor, Jean-Claude Gaudin, prides himself on close ties to Jewish and Muslim communities. Since his election in 1995, he has presided over Marseille-Espérance, or Marseille-Hope, a consortium of prominent religious leaders: imams, rabbis, priests. At times of heightened global tension—during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, for example, or after the 9/11 attacks—the group meets to talk things over. The mayor has even approved construction, by the Muslim community, of a new Grand Mosque, expected to begin next year on two acres of land set aside by the city in the northern neighborhood of St. Louis overlooking the port. Rabbi Charles Bismuth, a member of Marseille-Espérance, supports the project as well. "I say let's do it!" he says. "We don't oppose each other. We are all heading in the same direction. That is our message and that is the secret of Marseille."

It's not the only secret: the unusual feel of the downtown, where immigrant communities are only a stone's throw from the historic center, is another. In Paris, most notably, immigrants tend not to live in central neighborhoods; instead most are in housing projects in the banlieues, or suburbs, leaving the heart of the city to the wealthy and the tourists. In Marseille, low-rent apartment buildings, festooned with laundry, rise only a few dozen yards from the old city center. There are historical reasons for this: immigrants settled not far from where they arrived. "In Paris, if you come from the banlieues, to walk in the Marais or on the Champs-Élysées, you feel like a foreigner," says Stemmler. "In Marseille, [immigrants] are already in the center. It is their home." Sociologist Viard told me, "One of the reasons you burn cars is in order to be seen. But in Marseille, kids don't need to burn cars. Everybody already knows they are there."

Ethnic integration is mirrored in the economy, where Marseille's immigrants find more opportunity than in other parts of France. Joblessness in immigrant neighborhoods may be high, but it's not at the levels seen in Paris banlieues, for example. And the numbers are improving. In the past decade, a program that provides tax breaks to companies that hire locally is credited with reducing unemployment from 36 percent to 16 percent in two of Marseille's poorest immigrant neighborhoods.

But the most obvious distinction between Marseille and other French cities is the way in which Marseillais see themselves. "We are Marseillais first, and French second," a musician told me. That unassailable sense of belonging pervades everything from music to sports. Take, for example, attitudes toward the soccer team, Olympique de Marseille, or OM. Even by French standards, Marseillais are soccer fanatics. Local stars, including Zinedine Zidane, the son of Algerian parents who learned to play on the city's fields, are minor deities. "The club is a religion for us," says local sports reporter Francis Michaut. "Everything you see in the city develops from this attitude." The team, he adds, has long recruited many of its players from Africa and the Arab world. "People don't think about the color of the skin. They think about the club," says Michaut. Éric DiMéco, a former soccer star who serves as deputy mayor, told me that "people here live for the team" and the fans' camaraderie extends to kids who might otherwise be out burning cars. When English hooligans began looting the downtown following a World Cup match here in 1998, hundreds of Arab teenagers streamed down to the Vieux Port on Vespas and old Citroën flatbeds—to battle the invaders alongside French riot police.

Some 2,600 years ago, legend has it, a Greek mariner from Asia Minor, named Protis, landed in the inlet that today forms the old harbor. He promptly fell in love with a Ligurian princess, Gyptis; together they founded their city, Massalia. It became one of the ancient world's great trading centers, trafficking in wine and slaves. Marseille survived as an autonomous republic until the 13th century, when it was conquered by the Count of Anjou and came under French rule.

For centuries, the city has lured merchants, missionaries and adventurers from across the Middle East, Europe and Africa to its shores. Marseille served, too, as a safe haven, providing shelter for refugees—from Jews forced out of Spain in 1492 during the Spanish Inquisition to Armenians who survived Ottoman massacres early in the 20th century.

But the largest influx began when France's far-flung French colonies declared independence. Marseille had been the French Empire's commercial and administrative gateway. In the 1960s and '70s, hundreds of thousands of economic migrants, as well as the pieds-noirs, flocked to France, many settling in the area around Marseille. Amid ongoing economic and political turmoil in the Arab world, the pattern has continued.

The coming of independence dealt a blow to Marseille's economy. Previously, the city had flourished on trade with its African and Asian colonies, mainly in raw materials such as sugar, but there was relatively little manufacturing. "Marseille profited from trade with the colonies," says Viard, "but received no knowledge." Since the mid-1980s, the city has been reinventing itself as a center for higher education, technological innovation and tourism—the "California" model, as one economist described it. Along the waterfront, 19th-century warehouses, gutted and refitted, today provide luxury office and living space. A silo, once used to store sugar offloaded from ships, has been transformed into a concert hall. The old Saint-Charles train station has just been completely renovated, to the tune of $280 million.

While Marseille may lack the jewel box perfection of Nice, a two-hour drive away, it boasts a spectacular setting—some 20 beaches; picturesque islands; and the famous calanques, or fiords, where rugged coves and scuba-diving waters are just minutes away. And for anyone willing to explore the city on foot, it yields unexpected treasures. From the top of Notre-Dame-de-la-Garde, the 19th-century basilica, views of the city's whitewashed neighborhoods, islands and the Estaque coast stretch to the west.

Back in the city center, Le Panier (panier means basket, perhaps connected to the fact that the ancient Greeks' marketplace thrived here) has preserved a quiet charm, with little traffic and coffeehouses where one can snack on a bar of dark chocolate, a local specialty. In the heart of the district, a complex of recently restored 17th-century buildings, La Vieille Charité, houses world-class collections of Egyptian and African artifacts. The extensive holdings, from 21st dynasty sarcophagi to 20th-century central African masks, contain treasures brought back over the centuries from the outposts of the empire.

The port is rightly celebrated, too, for its traditional dishes, particularly bouillabaisse, the elaborate fish soup incorporating, among other elements, whitefish, mussels, eel, saffron, thyme, tomato and white wine. Back in the 1950s, a young Julia Child researched part of her best-selling 1961 cookbook, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, in fish markets along the Vieux Port. She compiled her recipes in a tiny apartment overlooking the inner harbor. The plain-spoken Child may have called the dish "a fish chowder," but the surging popularity of bouillabaisse today means that in one of Marseille's upscale waterfront restaurants, a serving for two with wine may set one back $250.

On any given evening, in clubs that fringe La Plaine, a district of bars and nightclubs about a 15-minute walk up the hill from the Vieux Port, global musical styles, from reggae to rap to jazz to West African rap-fusion, pound into the night. As I strolled along darkened cobblestone streets not long ago, I passed a salsa club and a Congolese band playing in a Jamaican style known as rub-a-dub. On the outside wall of a bar, a mural showed a golden-domed cathedral set against a fantastical skyline of mosques—an idealized vision of a multicultural city on a cobalt blue sea that bears a striking resemblance to Marseille itself.

Not long before I left the city, I met with Manu Theron, a percussionist and vocalist who leads a band called Cor de La Plana. Although he was born in the city, Theron spent part of his childhood in Algeria; there, in the 1990s, he played in Arab cabarets, clubs he likens to saloons in the Wild West, complete with whiskey, pianos and prostitutes. Also around that time, he began singing in Occitan, the centuries-old language related to French and Catalan, once spoken widely in the region. As a youngster in Marseille, he had sometimes heard Occitan. "Singing this language," he says, "is very important to remind people of where they come from." Nor does it bother him that audiences don't understand his lyrics. As a friend puts it, "We don't know what he is singing about, but we like it anyway." The same might be said of Marseille: in all its diversity, the city may be difficult to comprehend—but somehow, it works.

Writer Andrew Purvis, the bureau chief for Time in Berlin, has reported extensively on European and African immigration issues. Photographer Kate Brooks is based in Beirut, Lebanon.

Books

The Rough Guide to Provence & the Côte d’Azur, Rough Guides, 2007

My Town: Ford p. 96 none, per AM

Presence of Mind, p. 102

A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World by Gregory Clark, Princeton University Press, 2007

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.